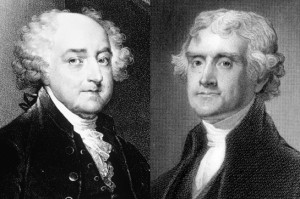

“I consider you and [Jefferson] as the North and South Poles of the American Revolution. Some talked, some rewrote, and some fought to promote and establish it, but you and Mr. Jefferson thought for us all.”

—Benjamin Rush to John Adams, February 17, 1812

Every law student has a responsibly to enhance the American Conversation—the eternal dialogue that is the American experiment. While it would be conceited and with reproach that I suggest we think like Messrs. Adams and Jefferson, we should, however, seek to become more thoughtful and attempt to engage in lively, educated discourse. Our national dialogue has increasingly been filled with a self-destructive, dysfunctional, do-nothing mentality that lacks reasoned thought. This trend is at best unproductive—at worst, destructive—to the American Conversation. As law students, we have the skills and responsibility to change this trend.

It is quite gratifying to obtain a deep understanding of a topic and then learn that you lacked a full appreciation for some of the more nuanced issues within that particular topic. Part of the legal learning process encapsulates this type of learning, where you learn a new approach or different perspective and it can—and should—be learned outside the classroom. It should go without saying that one the best places to learn is outside the classroom. But as law students, in the ultra-competitive school environment, we tend to focus on grades (and the job hunt) and lose focus of the big picture—developing the skills necessary to fulfill our duty to serve the public. As such, we would do well to be reminded of the importance of using the skills we have learned outside the classroom. While Dean Kearney reminds us to continue learning outside the classroom (e.g., in the many guest lectures, at On The Issues, and during social and award events at the Law School), the one place for learning that should continually reside in a predominant place in our minds is the Zilber Forum, a social area for discussion and contemplation. The Zilber Forum, or the idea of the Forum, does not and should not stay within the confines of the four walls (although the shape of the building may suggest three). This idea is already bursting at the seams of Eckstein Hall and with a little help from students will reach the community around us.

In the age of social media, our conversations and dialogue are increasingly viewed through Facebook posts, Tweets, blogs, and other emerging mediums. While these mediums can be used to increase participation, they often lack active and engaged thought. The age of anything-can-be-posted continues to increase individuals’ access to information (e.g., Wikipedia) but decreases incentive to actively participate and engage with the material. As younger generations continue to expand the use of social media, I am fearful that lively discourse will continue to dwindle.

But, there is hope. If we want a higher level of discourse, we must start with ourselves and then radiate that discourse outward. As students, we can start by picking up a newspaper, taking an interest in a different subject, giving back to the community, and engaging in thoughtful dialogue with other students (not to mention the myriad of professors who welcome a break from their research). From there, we can begin to create “mini-Forums” or circles of engagement: small groups of students who seek to discuss issues with well-informed and researched opinions. No doubt, passions will and should run high.

I am reminded of a recent discussion I had with a number of students about the reading of Miranda warnings to the Boston Marathon bombing suspect, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev. The discussion focused on when the warning should be given, whether an amnesty period should be instituted for public safety exceptions, and whether it is constitutionally permissible, as suggested by the Department of Justice and Federal Bureau of Investigations, that there is a national security exception to the Fifth and Sixth Amendments, or whether this type of issue should be taken up under the public safety exception. This well reasoned and thoughtful debate allowed participants to push the limits of their different theories, get immediate feedback on potential problems with their logic, and, more importantly, gain an appreciation for others diverse views. The added advantage of this debate was that each member was forced to confront the sometimes unobvious, but well-placed counterarguments, and reply. No doubt, this discussion will be remembered long after I have graduated.

The starting point for increasing the educated level of national discourse begins with self-development. Then a slow outward reach to those around us can start to transform the micro-debates and gain traction outside our individual groups. To be sure, this will be a long and slow process, but what other choice do we have than sit on our hands and do nothing? If I have not convinced you that we should dial up our national conversation, or if you are reluctant to start to reach outward, perhaps I can leave you with words of wisdom from multiple professors (including Professors Mazzie and Oldfather) about achieving inner dialogue: write a haiku. If I have failed a second time, perhaps thinking about the human experience through poetry can gain additional credibility by quoting John Adams: “You will never be alone with a poet in your pocket.” Law students have both the ability and the responsibility to enhance our national discourse; let’s not disappoint.