In the first post in this series, I compared black and white arrest rates in Milwaukee over time. In this post, I present arrest data by offense type.

In 2011, the seven leading arrest offenses were disorderly conduct, “other assault” (i.e., not aggravated assault), drug possession, theft, vagrancy, vandalism, and weapons possession. Together, these seven offenses accounted for more than 53 percent of all Milwaukee Police Department arrests. This amounts to almost exactly ten times the number of arrests for the violent “index crimes” — the most serious violent offenses that dominate media coverage of the criminal justice system (homicide, robbery, forcible rape, and aggravated assault). To get a more realistic sense of the day-in-day-out work of the system, it may be helpful to appreciate that for every homicide arrest you see in the news, there are 123 arrests for disorderly conduct and 47 arrests for simple drug possession — nearly all of which fly well below the media radar screen. It is an interesting question to what extent these lower-level arrests contribute to public safety.

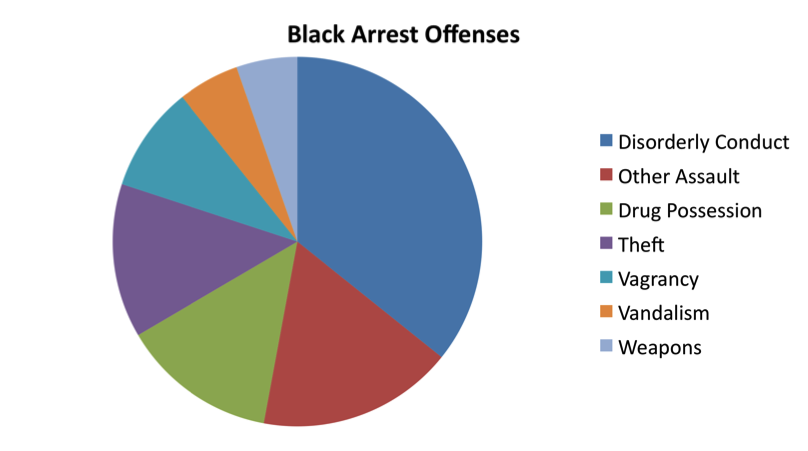

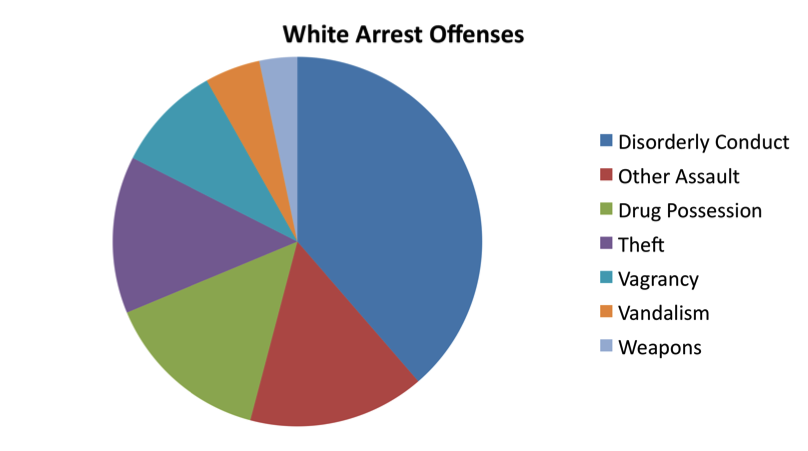

These offense distributions do not differ much by race. The first pie chart below indicates the distribution of the Big Seven arrest offenses among blacks; the second provides the distribution among whites.

It is often suggested that the War on Drugs has played a leading role in driving racial disparities in the criminal justice system. However, at least at the arrest level, drug enforcement does not particularly stand out in this regard. Total drug arrests (trafficking and simple possession) amounted to just ten percent of black arrests; for whites, the number was only slightly lower at nine percent. Racial disparities do not seem especially associated with drug arrests, but are rather more-or-less uniformly present across a range of major arrest categories. (It is uncertain which of these disparities, if any, are warranted by underlying racial differences in crime-commission. There is really no objective way of knowing, for instance, whether blacks are responsible for three times as much disorderly conduct as whites.)

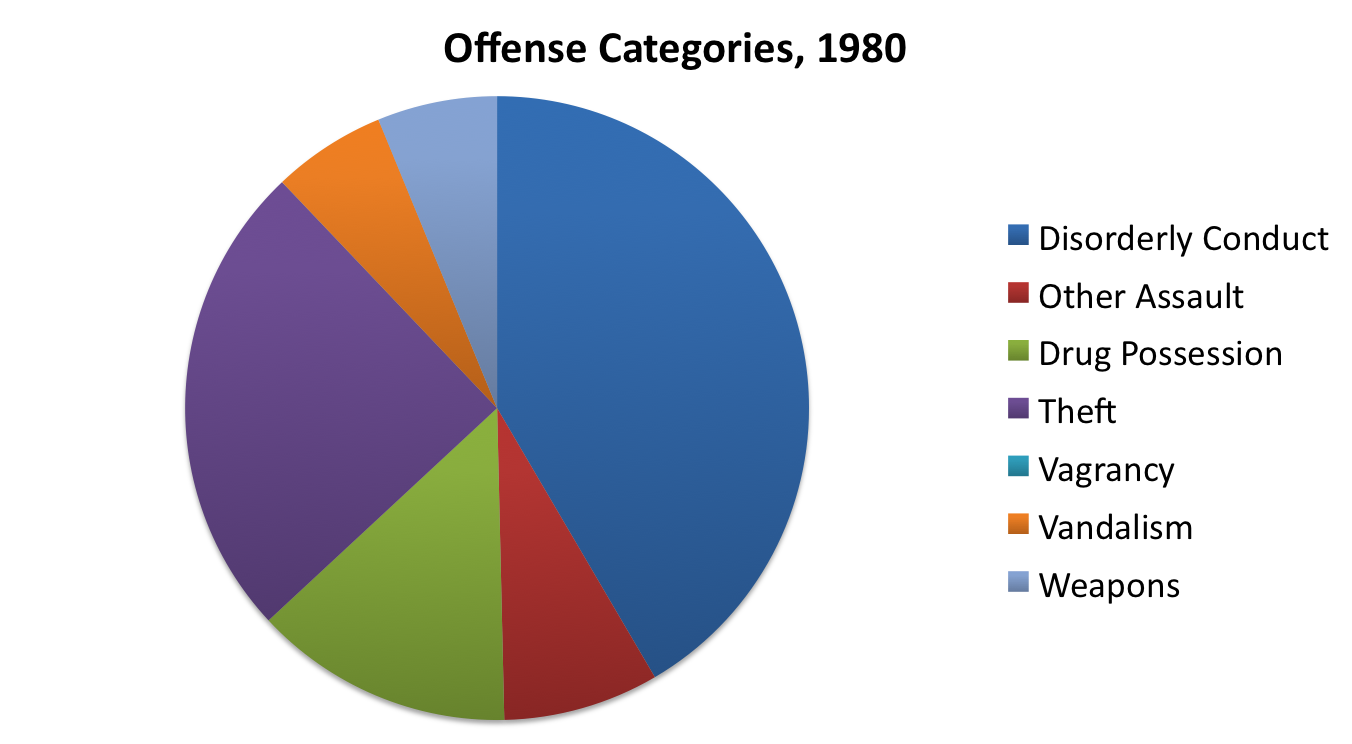

The picture looked rather different three decades ago. Here is the distribution of arrests of the 2011 Big Seven in 1980:

Most notably, theft arrests played a much more prominent role in 1980, while vagrancy arrests were almost unheard of.

Overall, the top seven offenses in 1980 were disorderly conduct, theft, drug possession, DUI, burglary, simple assault, and weapons possession. In 1980, the MPD made 1,856 more theft arrests, 1,482 more DUI arrests, and 1,309 more burglary arrests than in 2011. There were 3,852 more arrests in 1980 for the property index crimes (which include theft and burglary), but 728 fewer arrests for the violent index crimes. Does this reflect a reorientation of police strategies since 1980 away from the protection of property in favor of the protection of persons?

Based on FBI Uniform Crime Reporting data, violent crime in Milwaukee was 80 percent higher in 2011 than 1980, while property crime was 21 percent lower. So, the higher number of arrests for violent crime in 2011 likely reflects, at least in part, the fact that there were simply more violent criminals out there to arrest. By the same token, fewer property arrests likely reflects fewer property criminals. But it is probably too simplistic to say that changes in arrest patterns merely follow changes in crime patterns. For instance, the drop in property arrests (44 percent) was much higher than the drop in reported property crime, while the increase in violent arrests (36 percent) was much smaller than the increase in reported violent crime.

Note, too, that the FBI numbers only capture crime actually reported to police. National victimization surveys indicate that many crimes go unreported, but there is no way to know how common unreporting was in Milwaukee for any given crime category in any given year. For that reason, the FBI crime data must be interpreted with caution.

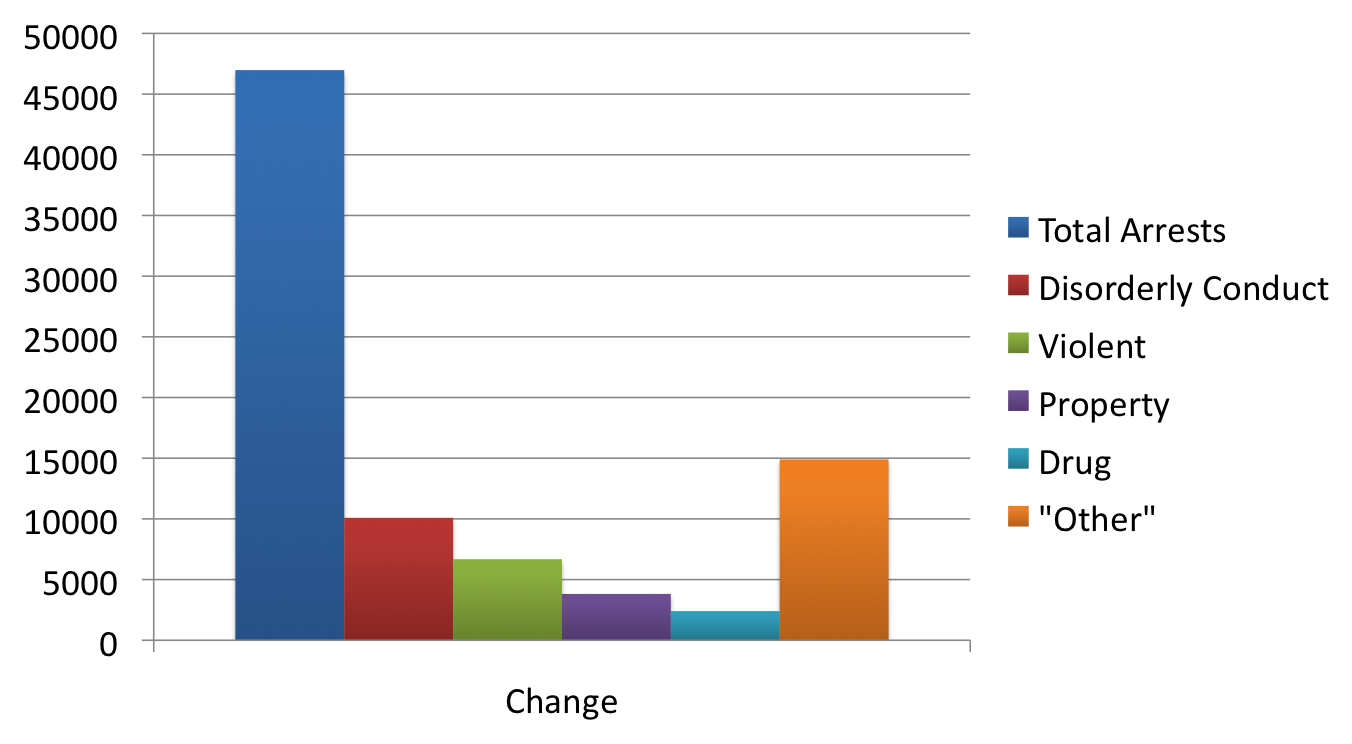

Returning to the arrest numbers, the offense-by-offense breakdown helps to illuminate the trends in black arrests discussed in the previous post. Black arrests spiked between 1980 and 1997. Here is what was going on with various offense categories in that time:

“Violent” here includes the violent index crimes plus simple assault. “Property” is the property index crimes. “Drug” is possession plus trafficking. And “other” is the residual category in the FBI data — a mysterious black box.

Again, the War on Drugs does not seem to be playing an especially prominent role in driving the spike in black arrests; in fact, the increase in black drug arrests was smaller than that of any of the other categories depicted.

It would be fascinating to know why the number of arrests of blacks for disorderly conduct increased 243 percent between 1980 and 1997, while the number of black residents of Milwaukee increased only about 45 percent.

It would also be good to know more about the impact these low-seriousness, high-volume arrests have on the individuals arrested and their families and neighborhoods.

In any event, the story since 1997 has been quite different:

Black arrests are down dramatically, and the decreases have been practically across the board. I say “practically” because there is an exception: drug arrests are up, albeit by a very small amount.

There is an interesting parallel here with the imprisonment data from Indiana, Minnesota, and Wisconsin that I analyzed in this article. Drug enforcement made only a modest contribution to the massive increase in imprisonment that occurred between the mid-1970’s and mid-1990’s. Since then, however, drug enforcement has played a more important role as a driver of incarceration.

Similarly, since the mid-1990’s, drug enforcement has been playing a relatively more important role as a driver of black arrests in Milwaukee. “Relatively” must be emphasized because, as discussed earlier in this post, drug enforcement is still not playing a major role in absolute terms.

The increasing importance of drug enforcement in the national criminal justice system since the 1990’s is ironic because public concern regarding drugs has actually declined markedly since then. In national public opinion surveys, for instance, concerns regarding drugs peaked in the early 1990’s. Further evidence of declining public interest in punitive responses to drug use can be seen in the proliferation of medical marijuana laws since the 1990’s, the decriminalization of marijuana use in two states last year, the rapid spread of drug treatment courts across the country, and the softening of many mandatory minimum sentencing laws for drug crimes, including the notorious federal crack law.

On the other hand, it is hard to know exactly what to make of the national trends in drug enforcement because there is a plausible argument that the War on Drugs is really a “War on Violence” by proxy. (This argument is discussed in detail in my article linked to above.) Drug enforcement may be intended less to punish drug crime per se, and more to prevent violence. It is yet another interesting question how effective and ethical drug enforcement is as a violence-prevention strategy.

In the next post in this series, I will compare Milwaukee’s numbers with Chicago’s.