PBS documentary Lincoln@Gettysburg paints a vivid picture of Lincoln and those close to him in the days surrounding his oration at Gettysburg. Lincoln’s wife Mary Todd begged him not to leave for Gettysburg because their young son Tad was seriously ill. He went anyway. Lincoln’s valet, William Johnson, an African-American free man, accompanied Lincoln to Gettysburg and listened to Lincoln practice his speech that morning. Lincoln left Gettysburg with a fever and came down with smallpox. Johnson died weeks later from smallpox after caring for Lincoln. Lincoln chose the inscription “Citizen” on Johnson’s tombstone, and Johnson was buried at Arlington cemetery.

PBS documentary Lincoln@Gettysburg paints a vivid picture of Lincoln and those close to him in the days surrounding his oration at Gettysburg. Lincoln’s wife Mary Todd begged him not to leave for Gettysburg because their young son Tad was seriously ill. He went anyway. Lincoln’s valet, William Johnson, an African-American free man, accompanied Lincoln to Gettysburg and listened to Lincoln practice his speech that morning. Lincoln left Gettysburg with a fever and came down with smallpox. Johnson died weeks later from smallpox after caring for Lincoln. Lincoln chose the inscription “Citizen” on Johnson’s tombstone, and Johnson was buried at Arlington cemetery.

And, Lincoln knew that his speech, just ten sentences long, would be transmitted by telegraph and printed in newspapers across the nation. Lincoln, in those ten sentences, was reaching out to the people at the Gettysburg ceremony, but he was also reaching out to the nation. It was unusual for presidents to give this type of speech in those days, but Lincoln accepted the invitation to speak at Gettysburg. Lincoln, it could be said, was a (social) media genius.

Listening to the words of the address spoken during Lincoln@Gettsyburg, I realized that not only is the address a great oration, but poetry. If you recite the address out loud, you can hear the rhythm, alliteration, and other elements of spoken poetry, and the words have different layers of meaning. For instance, “four score and seven years ago” refers to the Declaration of Independence of 1776, an intentional allusion to equality and liberty for all people. Lincoln masters imagery in words such as “honored dead.”

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate, we can not consecrate, we can not hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

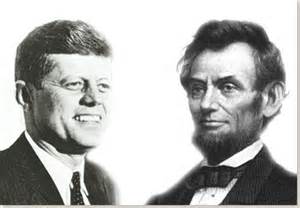

And now, this week the country mourns the anniversary of the assassination of another great president, John F. Kennedy. Both presidents can be remembered for their words, their living legacy. Kennedy is known for a number of key speeches he gave, but his speech at Amherst College, less than a month before he died, stands out in its lyrical quality. The speech was in honor of poet Robert Frost.

Our national strength matters, but the spirit which informs and controls our strength matters just as much. This was the special significance of Robert Frost. He brought an unsparing instinct for reality to bear on the platitudes and pieties of society. His sense of the human tragedy fortified him against self-deception and easy consolation. “I have been” he wrote, “one acquainted with the night.” And because he knew the midnight as well as the high noon, because he understood the ordeal as well as the triumph of the human spirit, he gave his age strength with which to overcome despair. At bottom, he held a deep faith in the spirit of man, and it is hardly an accident that Robert Frost coupled poetry and power, for he saw poetry as the means of saving power from itself. When power leads men towards arrogance, poetry reminds him of his limitations. When power narrows the areas of man’s concern, poetry reminds him of the richness and diversity of his existence. When power corrupts, poetry cleanses. For art establishes the basic human truth which must serve as the touchstone of our judgment.

This passage could be about Lincoln, as much as it is about Frost, for Lincoln had a personal sense of the human tragedy of the Civil War; he did not deceive or easily console himself about his role in the war. Lincoln’s address at Gettysburg was meant to give the nation strength and a vision for healing. Lincoln was aware of his power in sending soldiers to war, and his address may have been a personal effort to come to terms with that role. Kennedy too showed strong introspection in understanding the necessity of balancing power with poetry, art, and truth.