One of my favorite law review articles to assign to first-year law students is Kristen K. Robbins-Tiscione’s Paradigm Lost: Recapturing Classical Rhetoric to Validate Legal Reasoning, 27 Vt. L. Rev. 483 (2002). The article walks a reader through the legal paradigm and discusses how to effectively use deductive reasoning and reasoning by analogy to create a valid and persuasive argument. One of the takeaways from this article is that an advocate should include the facts, holding, and reasoning of a case precedent being used to explain a legal rule. “Facts, holding, and reasoning” becomes somewhat of a mantra in my first-year legal writing courses.

One of my favorite law review articles to assign to first-year law students is Kristen K. Robbins-Tiscione’s Paradigm Lost: Recapturing Classical Rhetoric to Validate Legal Reasoning, 27 Vt. L. Rev. 483 (2002). The article walks a reader through the legal paradigm and discusses how to effectively use deductive reasoning and reasoning by analogy to create a valid and persuasive argument. One of the takeaways from this article is that an advocate should include the facts, holding, and reasoning of a case precedent being used to explain a legal rule. “Facts, holding, and reasoning” becomes somewhat of a mantra in my first-year legal writing courses.

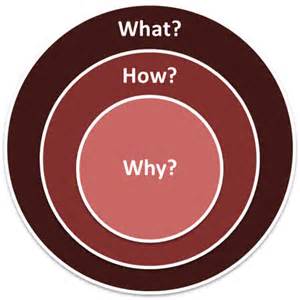

In teaching these concepts, over the years I have also come to use the phrase “how and why” to describe how students can deepen the way they write about the court’s reasoning. In my class, we use the term “holding” to mean the conclusion that the court came to when it applied the law to the facts. The “reasoning” is how and why the court came to that conclusion.

In analyzing the court’s reasoning, students must connect the rule they are explaining with the facts of the case. How did the court apply the rule to the facts, and what facts did the court find important? Why did the court choose those facts? Thinking about the reasoning in terms of how and why helps the students to pick out the sentences in the case that demonstrate the court’s thought process. I ask the students to look for concrete factual words in their sentences about the court’s reasoning, those words that reflect the facts that the court found most persuasive in its decision. Sometimes we also have to think about how to approach the court’s reasoning if the court did not state a reason for a particular conclusion. In that situation, it is appropriate to note that the court did not articulate its reasoning.

Students in a legal writing class are presented with a fictional problem set to analyze in writing. In the first year, they typically write sample internal office memos or sample briefs to a trial court. A student can also use “how and why” to deepen their analysis of their fictional case in their memos and briefs. In applying the rules of law to the facts of the fictional case, they must often analogize to the precedent. Analogy helps to fill in the analysis by showing how the facts of this case compare with the various precedent cases that the student cited to earlier when they were explaining the law.

If a student has fully developed their discussion of the case precedent in explaining the law, they will have an easier time comparing the precedent to the facts of their case. Considering how and why also helps to ensure that a student identifies and articulates those key facts in their written memo or brief. (After all, it’s one thing to think about and understand something, and another to write down that understanding.) One of the exercises a student can do in editing their draft is to highlight or underline each reference to the facts of the case precedent and each reference to their fictional case facts. Doing so helps them to see if they have missed facts they should have included, or to consider whether the words they used to describe the facts were accurate and sufficiently concrete and vivid.

Using how and why to help a student or advocate think through and articulate their reasoning, or the court’s reasoning, is not a novel approach. The “5 W’s”—who, what, where, why, when, (and some would add how)—trace their roots back to ancient rhetoric. In fact, Aristotle’s Art of Rhetoric is a great legal writing text, as the modern techniques we use to think through legal arguments directly derive from this work and other similar texts.

Cross-Posted at the Law School Toolbox.

As a newspaper journalist in my first career (law is my second), I TOTALLY get the value of “the five W’s!” Writing under deadline, those were like a lifeline in the olden days when reporters actually had to waste valuable time finding a PAY PHONE to call in a story with.

I’ve also found it very time-saving, when presented with a legal question that I don’t know anything about and a deadline looming, to think like a journalist rather than a lawyer. To wit: instead of trying to solve the mystery entirely by yourself and spend days reinventing the wheel, try to figure out who already knows something about it and pick their brains for insight.