Why Partisanship Bothers Us

With the Marquette Law School conference “Dividing Lines” approaching on May 15, it is worth asking why hard and determined forms of partisanship so unnerve us.

With the Marquette Law School conference “Dividing Lines” approaching on May 15, it is worth asking why hard and determined forms of partisanship so unnerve us.

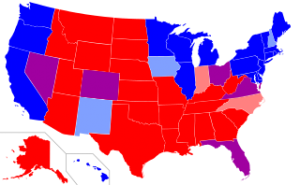

The immediate occasion for this discussion is Craig Gilbert’s study of political polarization in the Milwaukee metropolitan area, and its economic and cultural origins. Gilbert is the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel’s Washington bureau chief and this past year served as the Law School’s Lubar Fellow for Public Policy Research. Working with Charles Franklin, professor of law and public policy and director of the Marquette Law School Poll, Gilbert has documented in recent elections a strong and consistent correlation between voting preferences and race, ethnicity, education, and population density (the series to date appearing in the newspaper here, here, and here, with the final entry coming this Wednesday). Marquette Law School’s Professor David Papke has also commented on Gilbert’s research, noting how deliberately conceived public policies such as restricted covenants, exclusionary zoning, and easing of residency rules for municipal employees have contributed to the climate of divisiveness.

As a scholar of journalism and media, I want to probe more deeply the meanings Americans attribute to their experience of political division.

I am pleased to announce that our guest blogger for May will be Ric Gass ’70, of the law firm of

I am pleased to announce that our guest blogger for May will be Ric Gass ’70, of the law firm of