Once upon a time . . .

Once upon a time . . .

I started my last post with those same four words, so I hope you’ll forgive me the repetition. They’re good words for a beginning (though perhaps not in a piece of legal writing!). But why are they such good words to start with? I could wax poetic about creating a sense of nostalgia for a time long past, where wonderful things were possible . . . but that’s not it. They’re good words for a beginning because we all know what comes after them: a story.

Stories are powerful things. For millennia, human beings have told each other stories. We pass down knowledge and wisdom, warnings and inspiration to each other through tales. Myths from cultures all over the world and all throughout history were created to explain natural phenomena, and to try to answer questions about the deeper meaning of human existence. Folk tales and fables teach lessons about hubris and humility, social values and the dangers of greed and other vices. In the Christian Bible, Jesus teaches using parables that will be familiar to anyone who went to Sunday School—the mustard seed, the prodigal son. Why? Isn’t it easier to say, for instance, “Don’t be too greedy!” than to tell the story of King Midas? Easier, perhaps. But stories are memorable.

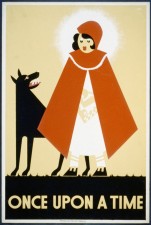

Human beings are good at remembering stories. From ancient epic poems to relatively more recent folklore, humanity has a rich oral tradition based on this fact. Works were memorized, told and re-told, and disseminated throughout their respective cultures. Even today, if I asked you to tell me a story, you might think of a myth or a folktale, classics like the story of Icarus, or Red Riding Hood. You can probably recall the details of those stories, even if you haven’t thought of them in a long time. That’s the power of stories; they linger in our imaginations.

Now at this point, you may wonder why I’m spending all this time on fairy tales. Isn’t this supposed to be a law-related blog post? Well, it is. Understanding and learning how to craft a narrative can be immensely valuable in legal writing. Stories are persuasive, and knowing how to tell a story may be the difference in convincing a factfinder to believe your version of events, rather than your opponent’s. It’s valuable to know how to craft a short narrative arc that leaves a lasting impression. But even more than this practical application, stories are essential to the study of law.

The case-based system we use to learn the law is not so unlike the storytelling we humans have done all throughout our history. What are the cases we study, and the hypotheticals we create and work through, if not stories? True, the “moral” we reach at the end may be quite a lot longer and more detailed than Aesop’s one-line axioms, but when we look at the facts of a case, at heart we’re reading a story. Many of the most important cases we read rely on their historical context as well as the bare facts, and that also becomes part of the story. Putting together the complete narrative in your mind as you look at a case can be immensely helpful, not only to help understand the actual outcome and the role of the case in the law, but also to help you remember and recall it later.

This applies to hypotheticals, too. When you make up your own hypos to practice with, be creative! Tell stories you’ll remember later on! You’ll be better able to pick up on it when a similar set of facts shows up again—either in a future case, or on an exam. And as we all know, in law school, being able to issue spot and recall relevant rules on your exams is critical if you want to live happily ever after.