I don’t have a handy quote to use as an epigram, but I’m sure that someone has previously, and pithily, expressed the idea that we travel as much to learn about ourselves as to learn about others. It’s the original form of comparative analysis, a chance to experience other ways of living and doing and thereby to reflect upon our own. The immediate effect is (often) the experience of novelty – at root the same thrill that accompanies exposure to a new idea, taste, or sound. “Here is something I haven’t seen before!” The lingering effect is that of evaluation, an effort to understand. We humans like to categorize, and so the urge is to place this new experience within our existing mental boxes. But the fit is not always perfect. When that happens we have to adjust the boxes, and thus our sense of the world. (Of course, there is a danger here, too. We might be so tempted to place things in our existing boxes that we overlook differences.)

I don’t have a handy quote to use as an epigram, but I’m sure that someone has previously, and pithily, expressed the idea that we travel as much to learn about ourselves as to learn about others. It’s the original form of comparative analysis, a chance to experience other ways of living and doing and thereby to reflect upon our own. The immediate effect is (often) the experience of novelty – at root the same thrill that accompanies exposure to a new idea, taste, or sound. “Here is something I haven’t seen before!” The lingering effect is that of evaluation, an effort to understand. We humans like to categorize, and so the urge is to place this new experience within our existing mental boxes. But the fit is not always perfect. When that happens we have to adjust the boxes, and thus our sense of the world. (Of course, there is a danger here, too. We might be so tempted to place things in our existing boxes that we overlook differences.)

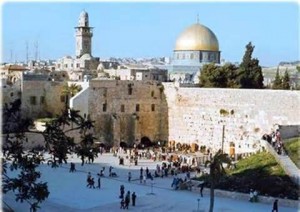

Why the holding forth on travel? I will tell you. I had the opportunity to accompany Professor Andrea Schneider and the thirty-three students in her International Dispute Resolution class on their trip to Israel over Spring Break. It was an amazing trip. We encountered theory in the classroom, and the reality of conflict, borders, and displacement outside of it. The people who showed us these things, both the theoretical and the concrete, are themselves deeply immersed in the effort to achieve peace and mitigate the consequences of conflict. Even what might appear to have been the more conventionally touristy parts of the trip – typically involving some historically and/or religiously significant site –served to underscore just how layered and tangled the region’s issues are.

An admission: I came to the trip as someone who has traveled fairly extensively within the US and Canada, and almost not at all elsewhere. That latter part happened mostly by accident, a product of growing up in a world where people didn’t do much traveling, not so much because of lack of curiosity about the world as because of lack of money. Vacations of any sort were mostly for other people, doubly so the kind that involve leaving the country. (The list of states I had been in when I boarded the flight to go to Boston for college: Minnesota, Iowa, Wisconsin, Missouri.)

I reached the end of my formal education not having traveled abroad. And then it was easy enough to let life get in the way. Lengthy vacations seemed unwise to the new lawyer, new parent, new law professor. Even now the prospect of taking eight days away from the enterprise of keeping our family running – with its delicate balancing of two careers and three kids whose activities require considerable chauffeuring on a daily basis – seemed increasingly unwise as the departure date drew near. There are at least two lessons here. One is that it’s probably a good idea to fit some international travel in during the course of one’s formal education, if it can be done. The other is that precommitment is a powerful thing. If I had first been presented with the chance to go on this trip a month or a week in advance, I’d have found a thousand reasons not to do it. But I committed to it a year or so in advance. From that perspective the benefits seemed clear, the inconveniences minor and abstract. I bound myself to it, and the inconveniences would have to be dealt with when the time arrived. They were.

I wrote the first draft of this less than twenty-four hours after having returned home, and while I was very much in the process of moving from immediate impressions to evaluation. In most respects the immediate impressions were overwhelmingly positive. This was an intensive educational experience, an almost perfect balancing of hearing about things in the classroom and seeing and experiencing their reality. We met with people who have been deeply involved in the processes of attempting to achieve peace, we saw the geography of conflict, with its fences and checkpoints and arbitrary lines, and we experienced both the difficulties and the joys of communicating through cultural and linguistic barriers.

Having said all that, a bit more self-indulgence. There was one sense in which my immediate impression was one of disappointment. When I was young (in my early twenties, say), trips to new places were exhilarating. I’ll never forget, for example, my first venture into New York. It was the mid-eighties, and Manhattan was still a comparatively dangerous place, a point brought home when my college roommate, a native of a New Jersey town just across the Hudson, told me to stuff my wallet in my socks as a precaution against the pickpockets and muggers who would be waiting for us on the other side. To a child of the very rural Midwest, this was new, and it was thrilling.

It has been a long time since travel brought about that feeling, and I hoped that with a flight across an ocean involved it might happen again. It didn’t. The architecture of Jerusalem and Haifa and Tel Aviv differs some from what we are accustomed to, and the language was different and the many layers of human history much more apparent on the surface. But whether it is a testament to the basic templates of human civilization, the massive influence of American culture, or just a packed schedule leading to a lack of time to sit and simply notice differences, my overwhelming sense was one of familiarity. It turns out that people are people. I am not suggesting that the differences aren’t there, but they struck me as differences of degree rather than kind. It’s an obvious point, perhaps. But for me, only in retrospect.

The processes of evaluation are still underway. Here is what I have for now. There seems to be a temptation to return from an experience like this and offer up confident conclusions about what a place or a people is like. To do so, I think, is folly. It’s been a common experience for me that the more I learn about something, the more I realize how little I know about it. (And as a consequence I instinctively distrust those willing to offer confident opinions on topics ranging far and wide. It’s a stance I recommend to you as well.) I know more – much more – about the history of Israel and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict than I did two weeks ago. A large part of that knowledge is a deepened appreciation of its complexity, and of how little I truly understand it. This should come as no surprise. To reflect on a different example: I lived in Oklahoma City for three years, a place that is culturally distinct from what I had been familiar with, but to a lesser degree than Israel. That three years gave me a strong sense of OKC, but I could not say, when I left, that I fully understood the culture of the city or the state. So it is, after a mere week, with Israel. The cultures, and their interactions, are as layered and complex as the history that is so much more evident in the geography, architecture, and artifacts.

As travelers, we saw a world in which it is easy to perceive the problems – the border disputes, the security measures, the disparate treatment, and so on. It is just as easy, from that perspective, to imagine solutions. In the last class meeting before we left we heard from an Israeli negotiator who alluded to the fact that all sorts of outsiders find it easy to offer assistance in the form of confident conclusions about what should be done. What outsiders consistently fail to account for, though, is the political reality, the sheer difficulty given all the moving parts in play, of getting from where things are to where things ought to be, and that is so even when all sides have at least rough agreement on the nature of where things ought to be.

There were many moments in this trip that illustrated the point, but for me the most poignant came during a session with a panel of students and faculty at Bar-Ilan University. One of our students asked a question concerning the panelists’ perspectives on the solution to the Israeli-Palestinian situation. One of the Bar-Ilan students offered her view of the right answer, using tentative and qualified language to do so. A faculty member then noted the difficulty of talking about the issue, and how that difficulty led to a tendency to ignore or avoid the topic. This collective inability discuss an obvious problem seemed puzzling at first. But a moment’s reflection reveals that it is perfectly, if unfortunately, natural. We in the U.S. have our parallels. Race relations are perhaps the best example. We have a huge problem in the US, but the accumulated history makes it difficult to discuss, much less to solve. And we have our issues with borders, some of which run right through what otherwise would be a single community.

Just as, to my eye, the differences between life in Israel and life in the U.S. are matters of particulars rather than fundamentals, so too with our problems. We have different cultures, different languages, different histories. All of these shape our thoughts and perspectives in ways that make it difficult, at best, for the outsider to truly understand what is going on. But at bottom we are all humans, and all subject to the same sorts of motivations and blindspots. And that’s an important realization, too. One lesson that we might draw is that because we cannot hope to truly understand another culture, we have nothing to offer it by way of assisting in the solution of its problems. I do not think this is the correct lesson. The outsider should be aware of the limits of his knowledge. But having done so he may be better positioned than the insider to offer a perspective on what is truly important, and on where the solution to a problem might lie.

We did not return from Israel prepared to solve the problems of the Middle East. We did bring back with us a deepened understanding of its people and its problems. And as we reflect on and evaluate our experiences, I think that we will find that we also learned some important things about ourselves.