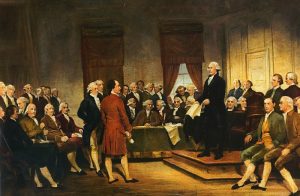

Part Four of a Six Part ser ies on Election Law, providing context to our system of government, our election process and a little history to evaluate and consider in the candidate-debate. Prior blog posts mentioned party-politics as having emerged during the Constitutional debate — in the framing days of the late eighteenth century, delegates began aligning along federalist and anti-federalist divides. Alignment shaped the compromise that became the Constitution of the United States, with the process of choosing the President — indirectly through electors — an example of compromise at work.

ies on Election Law, providing context to our system of government, our election process and a little history to evaluate and consider in the candidate-debate. Prior blog posts mentioned party-politics as having emerged during the Constitutional debate — in the framing days of the late eighteenth century, delegates began aligning along federalist and anti-federalist divides. Alignment shaped the compromise that became the Constitution of the United States, with the process of choosing the President — indirectly through electors — an example of compromise at work.

The compromised solution was complicated. Rather than allowing election by the populous or allowing Congress to choose the position, each state was given a number of “electors” and these electors would vote for the President.

Each state was left to determine the manner of selecting their electors, thus allowing the states a role in choosing the president. The electors would choose the president on the same day, all in an effort to even the playing field, as it were, in election and governance.

So how did it work, at least initially?

It was a problem.

As most Americans know, the guy on the dollar bill, George Washington, served as the first President. He took the position in 1789, and served roughly eight years. The Electoral College scheme, as ratified in the Constitution of the United States (Article II, Section 1, Clause 3), allowed electors to cast two votes at election time, without distinguishing between the President and Vice President. For Washington’s presidency, he was the leading vote getter, with John Adams, in second, elected to the vice-presidency.

But in 1796, the electoral scheme met its first challenge: a contested election. After nearly eight years of George Washington serving as President, the electoral-voting scheme — two votes — resulted in a split vote between electors. The Federalist Party candidate, John Adams, won the election. The Republican Party (borne of anti-federalist roots) candidate, Thomas Jefferson, finished in second place. Per the Constitution, Adams became the President and Jefferson the Vice-President.

More importantly, per the 1796 election, the country had two parties, ideologically opposed on key issues, occupying the top two positions in the executive branch.

Surprisingly, the two got along. Initially.

Not surprisingly, their agreeable relationship did not last long (perhaps days), only to see their views conflict throughout the next four years.

The party-conflict did not improve in the next election. In 1800, nominee Jefferson and a second Republican Party nominee, Aaron Burr, both obtained a majority of electoral votes, tied at 73 votes apiece. Without a clear winner, and per the Constitution, the decision on who would be the next President was a decision for the House of Representatives. There, the House took ballots — representatives did this 35 times, deadlocking on each, with neither candidate receiving the necessary majority vote of the state delegations (the votes of nine states were needed for an election–each state had 1 vote per the Constitution).

Alas, the 36th ballot proved a winner for Jefferson, a victory made possible by Alexander Hamilton (of the Federalist Party) who, disfavoring Burr’s personal character (and later part of an infamous duel with Burr), helped move the choice to Jefferson.

Fast-forward to today’s media-managed society. Imagine what the American public would think about the election of 1800, played out front-and-center on CSPAN. Once again, it took 36 ballots to choose the president. Not one. Not ten. 36! Arguably choosing the President in the year 1800 was a reality show nearly two centuries before the first “reality show”.

No doubt that by the 20th or so dead-locked ballot, Congressional-members realized the electoral-mess of 1796 and 1800 wasn’t good for anyone, leading to the Constitution’s Twelfth Amendment (1803) which was ratified in time for the 1804 election. Per the Twelfth Amendment, electors cast separate ballots for president and vice president, thus avoiding the 36-ballot cabal over the top-spot.

The Twelfth Amendment is today’s election guide, along with Congressional-based election laws (3 U.S. Code, Chapter 1) and each state’s election rules.

Back to the history lesson. In 1776, when drafting the Constitution — and before the messy elections that would come a decade or so later — the question remained as to electoral voting: who is an Electoral College member?

As discussed in my prior posts, the solution required compromise.

Here too, the compromise solution to choosing electors was that each state would determine how to choose electors. That meant, primarily, kicking-the-can back to the state legislatures.

That’s how it works today.

Since the election of 1824 (which I will discuss in my next post), most states appoint their electors on a winner-take-all basis based on statewide popular vote. The exceptions are Maine and Nebraska (choosing electors by congressional district and, in some instances, resulting in a split vote between candidates).

Basically, if the majority of Wisconsin voters choose the Democratic Party candidate, then all of Wisconsin’s electoral votes go to the Democrats. The same would hold true for a majority that went Republican, Libertarian or other party candidate that achieved the majority. (Technically it would be a majority of the plurality, but that adds complexity to an already complicated system.)

Once again, the election is indirect. Although ballots list the names of the presidential and vice presidential candidates (who run on a ticket), voters actually choose electors when they vote for the President and Vice President. These presidential electors in turn cast electoral votes for those two offices. Electors usually pledge to vote for their party’s nominee, but some “faithless electors” have voted for other candidates — and if you are worried about this, it has not happened often and some states actually criminalize such conduct.

So are you still following? If not, then here is the importance of election by electors: it can produce odd results, and has.

And that of course will be the subject of my next post, “The Teaching Of Elections-Past.”