Part Two of a series providing context to our system of government, our election process and a little history to evaluate and consider in the candidate-debate.

Part Two of a series providing context to our system of government, our election process and a little history to evaluate and consider in the candidate-debate.

Anyone who has been part of a committee, whether it be in government, business, or even the local PTA, will recognize that the same discussion points come up over, and over, and over again. In the political realm, the issue is largely taxation. In the PTA, it’s fundraising. Between April 15th and the local bake sale, the same discussions are had, year after year after year.

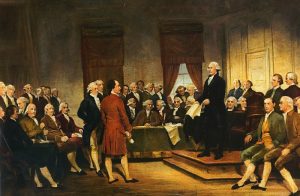

So imagine yourself in May of 1787, at the Constitutional Convention. The topic de jure was the present form of government — the Articles of Confederation — and how to improve on what was, by then, government gridlock (sound familiar?).

Those in attendance had a choice of throwing the baby out with the bathwater, as it were, or improving upon what got them there.

In retrospect, the choice of what to do was clear — out goes the baby — but in 1787 it was as clear as mud.

Keep in mind, the Articles of Confederation were years (decades) in the making, and were fashioned with state-interests in mind. Essentially, the delegates needed to ask themselves who they wanted to govern: themselves as states or a national government with power over the states.

And as the days dragged on, and as the weather changed from comfortable to hot, so too did the debate over what to do, how to do it, and why.

The debate lasted for more than three months.

Context is important. As of 1787, the alliance of states was only four years removed from the cessation of hostilities with England and those in attendance — generally the most wealthy and influential of the citizenry — had very real experience in dealing with a King. Issues such as “taxation without representation” and “quartering soldiers” were not simply concepts but real-life experiences.

Take the PTA example. Imagine you were given the choice between running your own bake sale or joining in with others in the group. Imagine further that the group — some of whom you have a personal distaste for — will determine what to sell, how, and why. You have a choice. Sure, the sale might be more successful when done as a group, but, then again, you have had some success on your own and certainly don’t want to hitch your wagon to people that, perhaps not overtly objectionable, you have concerns about. Ultimately, you decide the team will work better as a whole, and put trust in a process.

It was the same for the delegates, although with much higher stakes. (For more on the history, see my prior blog post, “How Many Years Does It Take To Bake A Constitution”.)

The beauty of the 1787 debate– and in many ways the beauty of the American-form of government — is that delegates were able to speak, debate and listen to each other despite disagreement. Indeed, less than a decade removed from kingly-rule, the delegates were set on creating a government that functioned without having a puppeteer pulling the strings.

Of course, what developed over the course of the Constitutional Convention had ramifications beyond the document itself as the very system of modern-day politics — that is, the “party system” — was taking shape. On one side were Federalists who favored a strong national governing body. On the other side were Anti-Federalists who, while in favor of a national governing body, wanted to reign in national powers.

So it was that the Constitutional Convention debated the role of the president, which I will discuss in my next blog, a debate that, perhaps not of the tenor or feel of our current climate, is worth understanding for today’s citizen that desires to understand our current election process.

The President of the United States — yet another piece of history to consider in how we got here — and the subject of my next post, “Who Do I Want As My King?”

It’s always interesting to learn about the history of our country. We can learn a lot about the present from our past.