This semester in Professor Lisa Mazzie’s Advanced Legal Writing: Writing for Law Practice seminar, students are required to write one blog post on a law- or law school-related topic of their choice. Writing blog posts as a lawyer is a great way to practice writing skills, and to do so in a way that allows the writer a little more freedom to showcase his or her own voice, and—eventually for these students—a great way to maintain visibility as a legal professional. Here is one of those blog posts, this one written by 3L Frank Capria.

Labor and employment law is an area of law that is of high importance. However, it gets little coverage or recognition. It does not get the publicity like criminal law does in hit TV shows like “Better Call Saul.” But, the Supreme Court is about to decide Janus v. AFSCME, which could dramatically change the entire public sector and make it right-to-work. This case will have a serious impact on teachers, firemen, police officers, and other public employee union members. If the Supreme Court rules mandatory collection of agency fees is unconstitutional, public sector unions will be weakened.

Policy

Right-to-work is a policy that allows dissenting union members to not pay non-political dues, or agency fees, to unions. Because of the exclusivity provision in the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), unions must still represent these dissenting members when negotiating the collective bargaining agreement or when the member is in an arbitration proceeding. The NLRA permits states to have right-to-work laws.

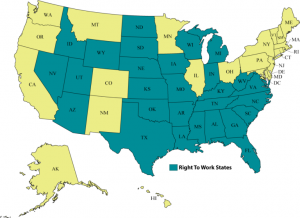

As shown in Figure 1, provided by National Right to Work Committee, twenty-eight states have adopted right-to-work laws, which include both public and private sector.[1] Kentucky and Missouri both adopted right-to-work in the past year, but it has not gone into effect in Missouri yet. Missouri will have a referendum in November 2018. There would be twenty-nine right-to-work states, but in 2011, voters in Ohio voted to repeal the law in a landslide.

History

In 2016, the Supreme Court heard Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association, and that case would have delivered the answer that Janus is seeking. However, Justice Antonin Scalia passed away and the U.S. Senate refused to give Merrick Garland a hearing. As a result, the ruling came out 4-4. This result meant no precedent was set by the Supreme Court and that the Ninth Circuit’s ruling would be binding for that jurisdiction. The Ninth Circuit held that public sector unions could require agency fees to cover the costs of collective bargaining and arbitration grievances.

In 2017, President Trump appointed Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court and the Senate confirmed Gorsuch to fill the vacancy of the late Justice Scalia. Gorsuch is expected to side with the other four conservative justices, all of whom ruled against the unions in Friedrichs.

Arguments

Typically, conservatives are in favor of right-to-work and liberals are against it.

Proponents of right-to-work argue that unions are political causes and that the agency fees are equivalent to speech. They suggest that anything a public-sector union does is political and that dissenting members cannot be forced to pay agency fees, especially because paying those fees forces the members to be associated with the union. Proponents argue that this violates their freedom of speech and association rights. Proponents also argue that forcing dissenting members to pay agency fees violates the principles of a free market because paying fees restricts the members from making a choice.

Opponents of right-to-work argue that the agency fees are not political but purely for employment purposes. The agency fees are meant for collective bargaining and representation during arbitration proceedings. Opponents bolster their argument by pointing out that the agency fees are used for collectively bargaining and arbitration grievances, and by not forcing the members to pay the agency fees, the dissenting members are freeriding, which gives the union fewer resources to fairly represent them. Opponents argue that the dissenting members do not have to work for the organization if they do not want to be in a union; because dissenting members have the freedom to contract, they can leave and work elsewhere. Lastly, opponents argue that if the Supreme Court rules the public sector is right-to-work, then the Court is legislating from the bench.

Conclusion

By June, unions will know their fate. The entire country will either be right-to-work for the entire public sector and the unions will have fewer resources, or right-to-work will be a decision left up to the states.

[1] This information is accurate as of April 17, 2018.

Missouri isn’t a right-to-work state, but somehow it is on your map.

Yes, correct.

Just saw this comment, but the article was written prior to the 2018 referendum that repealed the right-to-work law and has a note that says “as of April 17, 2018”. At the time, then Governor Eric Greitens signed the bill. The article was also written before Missouri moved the referendum from the general election to the primary election in August 2018.