The recent overall trends in Milwaukee county’s population are well known, but these headline figures obscure enormous variation between individual neighborhoods and suburbs.

Since 2000, the city’s population has declined a bit while the suburbs have, collectively, grown slightly. But within the city, neighborhood trajectories dramatically diverge, and population growth is really only limited to a specific set of pro-growth suburbs.

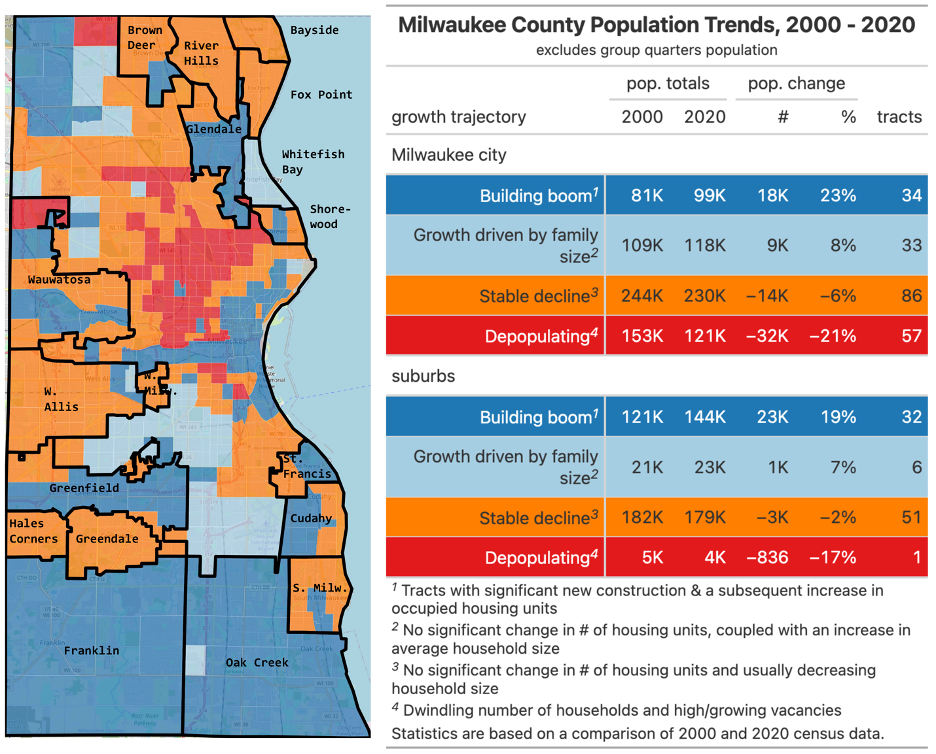

The graphic below categorizes census tracts into one of four demographic trajectories. “Building boom” neighborhoods (shown in dark blue) are building new housing and consequently increasing the number of households. In the city, this has mainly occurred in Greater Downtown (stretching from the north end of Bay View through the Lower East Side) as well as a cluster of subdivision-style housing developments on the far northwest side. All told, these areas have added 18,000 more residents since 2000, a 23% growth rate.

Glendale, Franklin, Oak Creek, Greenfield, and parts of St. Francis, Cudahy, and Wauwatosa have also grown thanks to new construction over the last 20 years. In total, the suburbs have added 23,000 residents in building boom tracts, a growth rate of 19%.

Most people in either the city or the suburbs don’t live in a tract that’s building more units. Instead, they live in a neighborhood with few empty lots, where the number of occupied housing units has remained steady, but with a slowly declining typical household size. This combination inevitably leads to gradual population loss. These “stable decline” neighborhoods are shown in orange.

In Milwaukee, they cover much of Bay View, the west side, and the northwest side. In total these neighborhoods saw a population decline of 14,000, or 6%. The suburbs of Brown Deer, River Hills, Bayside, Fox Point, West Allis, Hales Corners, and Greendale all followed this trajectory as well. The suburban population in stable decline neighborhoods fell by 3,000, or 2%.

The flip side of “stable decline” neighborhoods are the more unusual phenomenon of population growth thanks to increasing household size. Shown in light blue, these neighborhoods are mainly found on the south side of Milwaukee, with a few additional clusters on the north side. Generally, this reflects the presence of immigrant families with typically larger household sizes. Despite not adding more housing units, these neighborhoods increased their population by 9,000, or 8%, since 2000.

In the suburbs, this growth pattern is mostly limited to Whitefish Bay, which managed to slightly increase its average household size over the past 20 years, no doubt aided by the popularity of its school district.

Adding these three kinds of neighborhoods—building boom, stable decline, and family-size driven growth—yields a population growth of about 13,000 in the City of Milwaukee over the past two decades. But Milwaukee didn’t grow over that period. It shrank. The reason is the remaining category, “Depopulation,” shown in red.

These are tracts which experienced a dwindling number of households along with high and/or growing vacancies. In some places more than 1-in-5 housing units are vacant. All told, the population in these tracts fell by 32,000 (21%) since 2000. The population is declining because many households choose to leave when they can, and few people replace them. It’s easy to understand why. These are also the neighborhoods with the highest racial segregation, asthma-related emergency room visits, incidents of childhood lead poisoning, mass incarceration rates, absentee landlords, building code violations, etc.

Encouraging population growth in Milwaukee will require different strategies for each neighborhood type.

The current strategy of dense infill development in Milwaukee’s downtown is paying dividends. Wherever construction has boomed, demand is high and vacancy rates are low.

That style of growth is ill-suited to the “stable decline” neighborhoods where there are few empty lots appropriate for large-scale redevelopment. Finding ways to restore the historic population density in these neighborhoods will require creativity and regulatory reform. Zoning density standards need to be reformed—for instance, by removing the lot area per dwelling unit minimum requirement.

The city should allow the construction of accessory dwelling units by right. These are already common in Milwaukee (we call them “carriage houses”), but they are illegal to build today. Allowing people to replace their garages with small dwellings or to install “in-law” suites in their attics or basements is a key way to help popular neighborhoods like Bay View and Washington Heights maintain the population density essential to their historic, walkable commercial districts.

Immigration, and correspondingly high family sizes, have been a valuable source of growth in some neighborhoods. Milwaukee should do whatever it can to encourage and support immigrants, who have always been a key pillar of the city. But the level of immigration we receive is largely a function of national policies outside our control, and, in any case, neighborhoods with large families today are still trending towards a status of stable decline as household sizes predictably shrink.

Even if Milwaukee accomplishes all these things—developing new apartment buildings, densifying in-demand residential neighborhoods, and encouraging immigration—we will still probably shrink. The main driver of population loss in the city is depopulation in neighborhoods where decades of disinvestment has caused low quality of life. Solving this will take much more than real estate development; although, building quality affordable housing will certainly play a role.

Milwaukee has the potential to grow a lot. Within the city we have relatively affordable housing, compared to much of the country. We have adequate natural resources and basic infrastructure to support many more residents. And much of the city is already growing. Whether due to new construction or immigration, about 40% of the city’s residents already live in a neighborhood that grew over the last 20 years.

Currently, that success is limited to specific neighborhoods. Creating broad-based population growth will require building more towers where land is available, adding density in built-out neighborhoods that already have high demand, welcoming more immigrants, and—most critically—making the depopulating neighborhoods on the near north side attractive places for existing residents to stay.

This was an interesting read. Thank you for sharing with the public!