The debate over the appropriateness of Native American team names rages on. Whatever the propriety of generic Native American team names like Indians, Chiefs, Braves, or Warriors, or tribal names like Utes, Chippewas, or Seminoles, there seems to be a widespread belief that the term “Redskins” is especially offensive and insulting to Native Americans. How this perception came about is somewhat puzzling, as it appears to be of relatively recent origin.

There is little evidence that the perception of “redskin” as an inherently offensive term for Native American existed before the late 1970’s or early 1980’s. Traditionally, the word “redskin” was viewed as a synonym for Indian or Native American and did not carry the sort of negative connotations that have long attached to ethnic slurs like “chink,” “wetback,” “kike,” or “nigger.” Sportswriters covering teams with Indians nicknames during the first three quarters of the twentieth century routinely substituted “Redskins” for “Indians” or “Braves” in search of variety, and they apparently did so without being aware that this alternative word choice was more offensive than the original.

Although the name “Redskins” was earlier used by the Muskogee, Oklahoma, minor league baseball team and the Miami University of Ohio football team, the Redskins name is today primarily associated with the Washington team in the National Football League.

The team we now know as the Washington Redskins began its existence in 1932 as the Boston Braves. The name was changed to “Redskins” the following year. The new name was chosen in conjunction with the team’s relocation from Braves Park (named after Boston’s National League baseball team) to Fenway Park.

The name change was also consistent with team owner George Preston Marshall’s plan to market the team as one playing in the tradition of “Indian football.” (In the early 20th century, Native Americans were widely believed to be especially talented when it came to football, as borne out by the success of Indian college teams like Carlisle and Haskell and the Oorang Indians, an all-Indian NFL team from 1922 and 1923 which, like Carlisle a decade earlier, featured the great Indian athlete Jim Thorpe on its roster.)

Marshall’s plan for Indian football included hiring an “Indian” coach and several Native American Players, as well as adopting an Indian head logo and adorning all the players with war paint during games. This goal, of course, could have been accomplished just as easily had the team retained the name “Braves.” Moreover, there is absolutely no reason to believe that Marshall chose the name “Redskins” because he thought it was pejorative.

(It is not at all clear why anyone would name a team using a non-ironic ethnic slur, since to do so would be to impute supposedly unfavorable characteristics to one’s own players.)

Most likely, the name Redskins was chosen because it fit with Marshall’s plan to revive Indian football and because of the name’s similarity to Red Sox, in whose park the team was now playing. (The name “Indians” was apparently reserved for the NFL’s on again-off again Cleveland team.)

While one could argue that Marshall’s planned use of Native American imagery was a misappropriation of Native American cultural property, such an argument would apply whether the team was called the Braves or Redskins.

The historical record, in fact, shows that before the 20th century Native Americans frequently used the adjective “red” in reference to themselves and that the term “redskin” may have originated as a literal translation of a Native American term used to differentiate Indians from other Americans.

Moreover, widely used English language dictionaries in use as recently as the 1950’s and 1960’s reflect no acknowledgement that the term “redskin” was understood as disparaging to Native Americans.

For example, the 1952 edition of the Universal Dictionary of the English Language, described “redskin” as a “Native American Indian, a Red Man” (p. 981), but makes no reference to the word being offensive. The American College Dictionary (1956 ed., p. 1016); The Grosset Webster Dictionary (1957 ed., p. 1016); and Webster’s New International Dictionary, Unabridged 2nd Edition (1957 ed., p. 2088) all define “redskin” as a “North American Indian,” again, with no indication that the term was considered offensive. In The American Heritage Dictionary of the American Language (1969 ed., p. 1092), produced more than a decade later, the same definition is given, but with the qualification that the term is “informal” (which may be a recognition that “redskin” was passing out of everyday usage by the end of the 1960’s).

In fact, it was not until the 1983 editions of Webster’s Third International Dictionary and Collegiate Dictionary, 9th Edition that the Miriam Webster Company, the country’s leading publisher of “serious” dictionaries, added the cautionary phrase “usually taken to be offensive,” to its previous definition of “redskin,” which was simply “A North American Indian.”

In contrast, the same dictionaries from the 1950’s and 1960’s clearly indicate that the word “nigger” is understood to be offensive and derogatory. The comments so indicating range from “colloquial, contemptuous” (Universal Dictionary, p. 774) and “offensive” (American College Dictionary p. 820) to “substandard, now chiefly contemptuously” (Webster’s New International, p. 1651) and “vulgar” (American Heritage Dictionary p. 887). The Grosset-Webster Dictionary omitted the word altogether, presumably because it was in such bad taste.

While it is, of course, easy to find examples of pre-1980’s writings that disparage Native Americans while referring to them as Redskins (like Earl Emmons’ 1915 Redskin Rimes), it is even easier to find similar examples from the same era that use the word Indian while making derogatory comments (most famously, Gen. Philip Sheridan’s much repeated observation that “The only good Indian is a dead Indian”). Before the 1970’s, if not the 1980’s, there was a clear consensus that the word “redskin” was simply a synonym for “North American Indian” and was not widely recognized as a particularly offensive label.

In contrast, more recent dictionaries clearly identify the term “redskin” as disparaging. The Online Oxford Dictionary describes it as “dated and offensive.” Similarly, Merriam-Webster’s online dictionary identifies it as “usually offensive,” while the online Thefreedictionary defines it as “used as a disparaging term for a Native American,” and further classifies the term as “offensive slang.”

So what caused the meaning of the word Redskin to change when it did? Why did it become clearly offensive in the late 1970’s and the early 1980’s, when it has not been perceived in that way earlier in the century?

First of all, the meanings of descriptive adjectives, especially those with racial or ethnic connotations, do change over time. In my childhood, spent in the rural South during the final years of the Jim Crow era, we were taught that African-Americans preferred to be called “colored” or “Negroes,” and that to refer to such a person as “black” to his or her face would be insulting. I think this belief was generally held throughout the United States in the late 1950’s, and accurately expressed the views of most African-Americans as well (re: Negro College Fund and National Association for the Advancement of Colored People).

However, a decade later “black” had become the descriptor of choice for African-Americans, while “colored” and “Negro” had been cast into a linguistic dustbin. What was proper in 1959 had become awkward and unacceptable by 1969.

Moreover, beginning in the late 1960’s, the American Indian Movement and other Native American organizations began what turned out to be a largely successful campaign to convince other Americans that most of the stereotypical images of Native Americans in American popular culture were wildly inaccurate and insulting.

No art form contained more insulting images than the traditional American western. The 1970’s came at the end of an era in which the “Western” had been one of the dominant genres of American film, television, and popular literature. In westerns, the term “redskins” was regularly used in reference to nomadic plains Indians who were usually portrayed as “on the warpath.”

This repeated association of “redskins” with Indians of the American west in the post-Civil War era probably helped create an impression that a “redskin” was not just any Indian, but one that was particularly “savage.” As the notion that Native Americans were “savages” became increasingly untenable in the 1979’s and 1980’s, the word “redskin,” now increasing associated with the Indians portrayed in Westerns, may have lost its original generic qualities.

A second explanation comes from the fact the word “redskin” obviously uses a color to describe an ethnic group. While “black” and “white” became, somewhat ironically, the terms of choice identifying Negroes and Caucasians in the 1960’s, in the same era the practice of referring to Asians as “yellow” became verboten. Presumably, this stemmed from a belief that the use of the “yellow” label (as in “yellow peril”) was a manifestation of anti-Asian racism. Social pressure to drop “yellow” references did not affect the use of the terms “black” and “white,” but it may have had some impact on public attitudes toward defining Native Americans as “red.”

Finally, there is something slightly disparaging about the “skins” component of the word “redskins.” “Skins” can connote images of animal skins cut away from the body by fur hunters. While there is absolutely no basis to the frequently (and irresponsibly) repeated claim that the term “Redskins” once referred to the hides of Native Americans which could be exchanged for a bounty, there is something a little unpleasant about the similarity between “coonskin,” “deerskin” and “redskin.”

Also, in contemporary slang at least, “skins” has a number of negative connotations. The term refers to cigarette wrapping papers and, through an extension of image, it also refers to aimless teens that smoke, use drugs, and are sexually promiscuous. This secondary meaning may also give the word “redskin” unpleasant associations in our own time.

So, while it is difficult to pinpoint exactly when the meaning of “redskin” moved from innocuous to offensive, there is little reason to doubt that the general meaning of the term has changed (although polling data suggests that Native Americans are divided as to whether the use of the name Redskins by the Washington team is offensive). Moreover, the question of whether a business should be required to change its long-standing name because the meaning of one of the component terms has changed is a complicated question.

(A growing sensitivity to the representation of African-Americans in popular culture may have led to the cancellation of the Amos ‘n Andy television show, but Uncle Ben’s Rice and Aunt Jemima Pancake Mix are still on the market and still using versions of their traditional symbols.)

However, notwithstanding the changing meaning of the word “redskin,” there are other reasons to criticize the use of Native American imagery by George Preston Marshall’s football team. The real issue is not the choice of an “offensive” team name; the real issue is one regarding the boundaries of the right to appropriate someone else’s cultural property.

Before Marshall, teams that used Native-American team names rarely made much of an effort to exploit the Indian connection, unless the team was made up of Native American players. For Marshall, choosing a Native American name was only a start.

Even though the experiment with the war paint, the Indian players, the Indian coach (who, unbeknownst to Marshall, turned out not to be a real Native American) lasted only a couple of years, Marshall eventually realized that it wasn’t necessary to have real Indians to capitalize on the Native American connection. He retained the Indian imagery and expanded it to include a marching band wearing Indian headdresses, cheerleaders decked out in Indian princess costumes, and a fight song that was originally written in pidgin English and set to what were supposedly Indian rhythms.

No sports team had ever before attempted to exploit the use of Indian imagery on such a scale, but, after Marshall’s Redskins became popular, such features were widely imitated. Once he moved the team to Washington in 1937, the neo-Confederate Marshall further complicated the imagery by declaring the Redskins to be Dixie’s team. (In Marshall’s mind, the two groups, Indians and Confederates, were linked. His home town, Romney, West Virginia, is the location of an ancient burial mound that was turned into a Confederate cemetery during the Civil War.)

The real question regarding the Washington Redskins is whether or not non-Indian sports teams should have the right to exploit the cultural symbols of Native Americans. If they do not, then the Washington Redskins should become should change their name and imagery.

Of course, cultural property is notoriously difficult to define, and it not clear what the consequences would be were we to recognize even an informal proprietary on the parts of groups to their own cultural property. But that is the real issue involved in the Redskins controversy, not the meaning of the word “Redskin.”

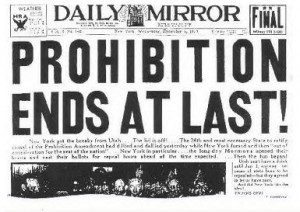

This past December 5 marked the 80th anniversary of the repeal of Prohibition, America’s experiment in the creation of an alcohol-free society.

This past December 5 marked the 80th anniversary of the repeal of Prohibition, America’s experiment in the creation of an alcohol-free society.