Rare is the presidential election in which American voters do not get peppered with the message that the choice to be confronted poses an alternative of monumental importance.

No less rare is the presidential election in which candidates and their surrogates refrain from accusing opponents of misrepresenting facts sufficiently often that even Pinocchio and Charles Ponzi would blush.

In these respects, the current contest—despite its conspicuous differences from those that preceded it—mirrors rather than diverges from those of the past.

Donald Trump’s uneasy relationship with truth provides full-time employment for factcheckers who once needed to supplement their incomes in other ways.

Tim Walz’s missteps have afforded folks thirsty for credibility no shortage of opportunities to demonstrate that the Fourth and Fifth estates hold Democrats to standards approaching the rigor to which they hold Republicans and their surrogates.

Yet one particular set of representations that has assumed a central role in the campaign continues to go unexamined, unchecked, unexplored. And, oddly enough, this neglect spans the breadth of the ideological spectrum, from Tom Cotton to AOC, from Fox News to MSNBC, from the Wall Street Journal, National Review, Heritage, and Cato to the New Republic, Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert, Slate, Mother Jones, CNN, and Brookings.

The Democratic ticket seeks to persuade the nation that the status of reproductive rights for women and their families will undergo a massive change should the Harris/Walz ticket emerge victorious. More specifically, the ticket would have us believe that its victory would lead to increased protection at the national level for these aspects of liberty guaranteed from 1973 up to the cataclysm that goes by the name Dobbs.

But the premise of such an argument remains flawed.

And it remains flawed for at least three reasons.

One is that the status of this once-upon-a-time freedom under federal constitutional law is certain to remain as it stands today for at least the next generation: non-existent. Put simply, while left-leaning law professors exhaled in the aftermath of the 1992 reaffirmation of Roe announced by a trio of Justices appointed by Presidents Reagan (O’Connor and Kennedy) and Bush 1 (Souter), opponents of abortion rights continued their effort to cobble together a coalition targeted to upend Roe and its progeny. A focused slice of the endeavor was to identify, cultivate, and elevate to the nation’s highest court individuals committed to the proposition that the reproductive liberty of women and their families was worthy of less constitutional protection than the potential life being carried by a pregnant woman.

Mitch McConnell knew well that a Justice Merrick Garland would pose an unwelcome obstacle to these efforts. After all, McConnell’s mama didn’t raise no fool. The Garland nomination thus withered on the 2016 vine.

The Trump Justices—Neal Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett—promptly completed the task with surgical-strike dispatch, joining Justices Alito and Thomas to remove the very federal constitutional protection that had been enshrined a half century earlier. To boot, that quintet received a crucial assist from an unlikely source: Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Yes: Historians will sidestep the contribution to the pro-life movement made by Justice Ginsburg in resisting overtures to retire during the second Obama term. That assist nevertheless looms large. It will continue to grow in magnitude even as pro-choice advocates who dominate the nation’s law schools raise their glasses to toast RBG at every opportunity. And do so at the very moment at which more than a few women across the nation scour the web for information about jurisdictions that will allow them to end an unwanted pregnancy.

A second reason pro-choice Americans should be skeptical about the changes a Harris/Walz administration would usher in concerns the prospects for Congress passing a law that would guarantee women the reproductive freedom recently lost by virtue of Dobbs. Simple arithmetic reveals why.

Rare is the prognosticator who believes Democrats will control each house of Congress come January. And even were such an unlikely development to unfold the same simple arithmetic reveals that the filibuster would be employed successfully in the Senate to prevent a national pro-choice law from reaching the floor for a vote. Quite simply: The talk of “codifying” Roe is now and over the coming few years will remain just that: talk.

Yet suppose pro-choice Americans persist in convincing themselves that my analysis misfires.

Suppose a Harris/Walz administration, assisted by a Democratic Congress, magically transforms the status quo and—poof!—brings into existence a national law that codifies reproductive freedom.

All this merely leads to the third reason a Harris/Walz administration will not succeed at restoring reproductive freedom at the national level. Unpacking this third reason to make it accessible to Americans whose attention span gets briefer with each passing day represents no easy task. But the daunting nature of the challenge has nothing to do with why the Harris/Walz campaign has steered clear of any effort to do so.

The same Supreme Court majority that delivered us Dobbs construes the enumerated powers of Congress narrowly.

Very narrowly.

More specifically: A core tenet of contemporary conservative jurisprudence is that the commerce power—the constitutional power that has anchored the bulk of law enacted at the national level since the New Deal—is permitted to reach only activities that are genuinely national in scope. Every indication is that the current Supreme Court views reproductive freedom as not such an activity.

Now: It matters not a whit that you, or I, or a pregnant neighbor down the block discerns that a self-evident paradox of Dobbs is to suffuse the plight of pregnant women with concerns that affect interstate commerce and mobility.

What matters, instead, is this: The same Supreme Court majority that refused to acknowledge the close and substantial relationship reproductive liberty bears to other long-established constitutional freedoms will be the majority telling us that views harbored by our eighteenth century “Framers” about subjects worthy of national legislative attention foreclose the authority of a twenty-first century Congress to pass a law that safeguards reproductive freedom without violating core tenets harbored by James Madison and his peers. Put bluntly, no such “codification” of Roe signed by President Harris would survive the scrutiny of what not all that long ago was dubbed the Roberts Court.

Candidate Richard Nixon’s “secret” plan to end the Vietnam war remained a secret for sufficiently long that America’s involvement in that conflict lingered until well after Nixon had left the Oval Office in disgrace.

The vow that emerged from the lips of candidate Bush 1—“no new taxes”—proved demonstrably false by the end of the second year of his administration.

A similar fate awaits the repeated suggestion that a Harris/Walz administration will bring about protection at the national level for reproductive freedom. In point of fact, the safeguards in place for that freedom at the national level when a hypothetical Harris/Walz administration comes to a close will bear an uncanny resemblance to the status of such safeguards today: regrettably non-existent.

Yet uttering that truth aloud—let alone doing so at the climax of a campaign during which the Harris/Walz ticket has sought to leverage the issue for all the votes it can garner—would make for a miserably disappointing rally. And a thirty-second television spot that would galvanize neither the Democratic base nor pro-choice Republicans who find themselves at the vital center in battleground states.

To paraphrase that Jack Nicholson line: We can’t handle the truth.

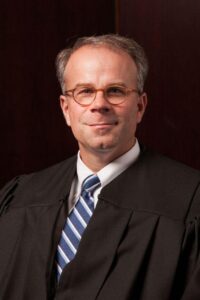

The Hon. Michael Y. Scudder, judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, delivered this year’s Hallows Lecture, yesterday evening, to more than 200 individuals in Eckstein Hall’s Lubar Center. The lecture was exemplary.

The Hon. Michael Y. Scudder, judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, delivered this year’s Hallows Lecture, yesterday evening, to more than 200 individuals in Eckstein Hall’s Lubar Center. The lecture was exemplary.