Federal Indian Law—the legal provisions and doctrines governing the respective statuses of, and relations among, the federal, state, and tribal governments—is replete with seeming anomalies when compared to the background of typical domestic law in the United States. The purpose of this post, and of the series of which it is a part, is to identify and examine such anomalies in an effort to acquaint readers with the metes and bounds of Federal Indian Law, while shedding some light on the origins and perhaps the future of this unique legal realm.

Federal Indian Law—the legal provisions and doctrines governing the respective statuses of, and relations among, the federal, state, and tribal governments—is replete with seeming anomalies when compared to the background of typical domestic law in the United States. The purpose of this post, and of the series of which it is a part, is to identify and examine such anomalies in an effort to acquaint readers with the metes and bounds of Federal Indian Law, while shedding some light on the origins and perhaps the future of this unique legal realm.

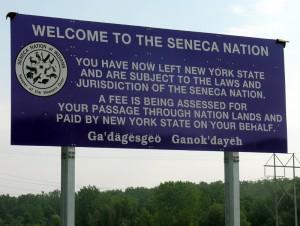

The prior post examined one such anomaly, namely, the permissibility of the government’s differential treatment of Indian tribes and their members despite the U.S. Constitution’s guarantee of equal protection. In this, the second installment in the series, another topic of significant contemporary interest will be surveyed. This is the oddly diminished character of Indian tribal sovereignty and, in particular, the extent to which tribes, in their own territories, lack criminal and civil authority over non-Indians or non-tribal members.

The capacity to enact and enforce laws is, of course, one of the hallmarks of sovereignty within the Western political tradition. This includes both criminal laws and civil laws, the latter often being divided into powers of regulation, taxation, and adjudication. It is typically accepted, moreover, that the reach of a sovereign’s laws extends along two axes: citizenship and territory. That is, the sovereign has the authority to govern not only its citizens but also all others who enter its territory. Thus, for example, inquiries into the jurisdiction of courts over a person or his property ordinarily entail an examination of the person’s citizenship and/or the relationship between the person’s conduct or property and the territory of the sovereign to which the courts belong.

In recent decades, however, Indian tribal sovereignty has increasingly been confined to a single axis—that of citizenship—leaving tribes largely powerless to enforce their laws against non-Indians who, within the tribe’s territory, commit criminal conduct or engage in activities that would normally be susceptible to regulation, taxation, or adjudication. Perhaps surprisingly, the institution primarily responsible for this diminishing conception of tribal sovereignty is not Congress, which the Supreme Court has repeatedly described as having “plenary power” over Indian affairs, but rather the Court itself.

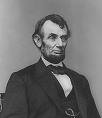

Reviewers of Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln” have rightfully praised the film for its faithfulness to history and for the fine acting of Daniel Day Lewis, Sally Field, and Tommy Lee Jones, among others. As a “lifer” in legal academics, I was intrigued by the film’s engagement with law, lawmaking, and law-related ideology.

Reviewers of Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln” have rightfully praised the film for its faithfulness to history and for the fine acting of Daniel Day Lewis, Sally Field, and Tommy Lee Jones, among others. As a “lifer” in legal academics, I was intrigued by the film’s engagement with law, lawmaking, and law-related ideology.