The Basketball Kings and the Football Colts are the Most Frequently Relocated Teams

Professional sports team relocations have been a feature of the American sports industry since the nineteenth century. Team owners have been willing to move from one city to another, and, occasionally, from one league to another, in search of greater profits. While some relocations have produced litigation and legislative efforts to regulate the movement process, in most situations the decision to move has been left to the team owner.

It now appears that the Sacramento Kings of the National Basketball Association are poised to move to Seattle, a city that lost its previous NBA team, the Supersonics, to Oklahoma City in 2008. Since the story broke, a number of publications, including the Wall Street Journal, have reported that the Kings are the most travelled major league sports franchise in American history. That is true, although at least one other current team can claim to have moved as frequently.

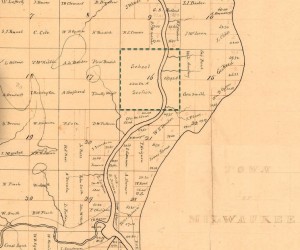

The current Kings began life in the 1920’s as a semi-professional team in Rochester, New York. In 1945, the Rochester Royals joined the National Basketball League, then switched to the Basketball Association of America in 1948, and in 1949, it was one of the inaugural teams of the National Basketball Association which was formed with the BAA merged with the NBL.

In 1957, the Royals moved to Cincinnati, and in 1972, they moved to Kansas City and Omaha, splitting their home games between the two cities. Because the American League baseball team in Kansas City was already known as the Royals, the team changed its name to the Kings. After the 1974-75 season, the team began playing all its games in Kansas City, where it remained until it moved to Sacramento in 1985. If they do move to Seattle, that will be the team’s sixth city.

However, a case can be made that the Indianapolis Colts of the National Football League have also played in at least six different cities. Here’s the argument.

From 1913 to 1916, the top semi-professional team in Dayton, Ohio was called the Cadets. In 1916, the team apparently became fully professional and changed its name to the Dayton Triangles. The Triangles quickly established themselves as one of the strongest professional elevens in the Midwest, and when the National Football League was organized in 1920 (originally as the American Professional Football Association) the Triangles were a charter member.

The Triangles played in the NFL until 1929, when the team finished last in the 12-team league with an 0-6 record while being outscored 136-7. (The 1929 championship was won by the Green Bay Packers who finished the season 12-0-1, which is still the second best record in NFL history).

At the conclusion of the season, the Dayton owners sold the team’s franchise to New Yorkers Bill Dwyer (a fomer NHL owner) and Jack Tepler (coach of the NFL’s Orange Toronados). The new owners moved the team to Brooklyn and renamed the team the Dodgers in imitation of the borough’s major league baseball team. (Trademark protection did not extend to team names in 1930.)

Given Dayton’s poor performance in 1929, the new owners made no effort to resign any of the Triangles, and instead recruited most of its players from the ranks of Tepler’s former players who had previously been under contract to the Orange Tornadoes. Either the NFL was not using a reserve clause in its contracts in 1929, or else the Orange team (which moved to Newark in 1930) decided that it was not worth going to court to prevent its former players from jumping teams.

In 1937, a 50% interest in the Brooklyn team was purchased by future New York (baseball) Yankee owner Dan Topping. Topping, who eventually gained complete control of the team, kept the Dodgers in Brooklyn, but in 1944, he changed the team’s name to the Brooklyn Tigers. The team had gone 2-8-0 in its final season as the Dodgers, but the name change hardly helped as the club finished 0-10-0 in 1944.

As a result of the wartime manpower-shortage, the Brooklyn Tigers combined with the Boston Yanks for the 1945 season. The largest number of the teams starters had played for Brooklyn in 1944, but the team was coached by Boston coach Herb Kopf, and the club played four of its five home games in Boston. (The fifth home game, with the New York Giants, was played in Yankee Stadium.)

(Combined teams were a feature of the NFL during World War II. In 1943, the Pittsburgh Steelers and Philadelphia Eagles combined for the season, and in 1944, Pittsburgh and the Chicago Cardinals did the same.)

However, after the 1945 season, Topping decided to move his team to the All America Football Conference, a new major league football enterprise designed to compete directly with the NFL. In the new league, Topping’s team was renamed the New York Yankees, and it played its home games in Yankee Stadium. Although most of the Yankees were recruited from the ranks of returning veterans and recent college graduates, Topping brought several of the best of his Tigers/Yanks players with him to the new team, including fullback Pug Manders, tackle Don Currivan, and fullback Eddie Prokof, the first round draft pick of the Tigers/Yanks in the 1945 NFL draft.

To fill the gap opened by the move of the Tigers to the AAFC and in anticipation of a post-World War II sports boom, the NFL allowed the Boston Yanks—the Tigers former partner–to move to New York City where the team played as the New York Bulldogs.

After four seasons of competition, the two leagues agreed to merge. Cleveland, San Francisco, and Baltimore (the original Colts) were added to the ten team NFL, now (temporarily, as it turned out) dubbed the American-National Football League. Although the mechanics of the transaction are a little obscure, as part of the merger of the leagues, the AAFC Yankees and the NFL Bulldogs were permitted to merge into a single “second” New York team. Ownership of the combined team, called the New York Yanks, went to Bulldogs owner Ted Collins (who paid $1 million for the Yankees).

The combined team was coached by Red Strader, the former coach of the Yankees, and the vast majority of the team’s players had played for the Yankees the year before. Although the New York Giants were permitted to take several players from the Yankees as deferred compensation for allowing the new Yanks to move into their territory, nine of the eleven starters for the 1949 Yankees played for the 1950 Yanks. Essentially, Collins bought the Yankees and substituted them for his team in New York. Moreover, the similarity of team name, coach, and players undoubtedly led New York football fans to associate the 1950 NFL team with its 1949 AAFC predecessor.

Although the 1950 Yanks compiled a 7-5-0 record, the following year the team slumped to 1-9-2. At this point owner Collins decided to get out of the football business and sold his franchise to the league. The NFL in turn transferred the franchise to a group from Texas, who moved the team from New York to Dallas, where the team was dubbed the Texans. Along with the franchise came the roster of the 1951 New York Yanks.

The 1952 Dallas Texans tuned out to be one of the biggest disasters in NFL history. Not only did the team lose its first seven games of the season, but white residents of Jim Crow Dallas seemed reluctant to cheer for a team with black players. (Several of the former Yanks were African-Americans including star running back Buddy Young.) In their first four home games, the Texans never drew as many as 18,000 fans while playing in the 70,000 seat Cotton Bowl. After Game 7, a 27-6 home loss to the Los Angeles Rams in which the team drew just over 10,000 fans, the franchise was returned to the league.

The NFL moved the team offices to Hershey, Pennsylvania (near the NFL offices in Philadelphia), and the Texans played one of their two remaining home games in Akron, Ohio, and the other in Detroit against the Lions. With only a single victory over the Bears (in the Akron game), the Texans finished their only season at 1-11-0.

After the season, the abandoned Dallas franchise was awarded to Carroll Rosenblum of Baltimore who renamed the team the Colts. (The original Colts had folded after the 1950 season, becoming the last NFL team to go out of business.) The Colts initially flourished in Baltimore, but faltering attendance led the team to relocate to Indianapolis in 1984, where the team has played ever since.

So Dayton became Brooklyn and Brooklyn became New York after a one year stay in Boson. New York became Dallas and then Baltimore and then, finally, Indianapolis. Counting the temporary combination of 1945, the team has played home games in seven different cities. (I do realize that since 1898, New York and Brooklyn have been part of the same city, but for sports purposes, they have traditionally been treated as though they were two separate municipalities.)

It would be interesting to see the Colts play a “turn-back-the-clock” game next year wearing Dayton Triangle uniforms, but I am not holding my breath.