A Rainy Day in Boston

Our National Appellate Advocacy Competition adventures came to an end today. One team advanced to the semifinal rounds, and I tried to explain to the teams that their performances were really outstanding accomplishments. But I don’t think it helped much. We also learned that the Labor and Employment Law team failed to reach the finals; though, again, from my perspective, their performance was terrific.

Our National Appellate Advocacy Competition adventures came to an end today. One team advanced to the semifinal rounds, and I tried to explain to the teams that their performances were really outstanding accomplishments. But I don’t think it helped much. We also learned that the Labor and Employment Law team failed to reach the finals; though, again, from my perspective, their performance was terrific.

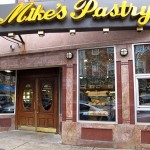

The rainy day here suited our mood pretty well. We consoled ourselves with Italian food and desserts at the North End. I think we’d all recommend Mike’s pastry.

It’s easier for me to say, being the coach and not the advocates, but I really do hope that the students can appreciate what an accomplishment it is to make such a good showing in these national competitions. Eventually, anyway. (I told them that I think it only took me about ten years to get over my own team’s loss in the National Moot Court Competition, when I was in law school.)