Massachusetts Attorney General and unsuccessful U.S. Senate candidate Martha Coakley’s error in labeling Red Sox pitcher Curt Schilling a Yankee fan was reminiscent of the late Senator Ted Kennedy’s tenuous command of the world of baseball. Few can forget his famous statement in 1998: “It is a special pleasure for me to introduce our two home run kings for working families in America, Mike McGwire and Sammy Sooser of the White House. Its a pleasure to introduce them.”

Massachusetts Attorney General and unsuccessful U.S. Senate candidate Martha Coakley’s error in labeling Red Sox pitcher Curt Schilling a Yankee fan was reminiscent of the late Senator Ted Kennedy’s tenuous command of the world of baseball. Few can forget his famous statement in 1998: “It is a special pleasure for me to introduce our two home run kings for working families in America, Mike McGwire and Sammy Sooser of the White House. Its a pleasure to introduce them.”

It looks like the good Senator is still up to his old tricks. In his posthumously published autobiography, he writes about his grandfather Honey Fitz Fitzgerald, the one-time Boston mayor and congressman and big-time Red Sox fan at the 1903 World Series. On page 78 of “True Compass,” he observes:

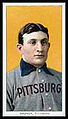

“Tessie” may sound a little quaint to today’s ears, but Grandpa’s rendition of it was good enough to cause the great Pittsburgh third baseman Honus Wagner to commit three errors in one inning during a World Series game.

“Third baseman Honus Wagner”? Also, Wagner did not make three errors in one inning during the 1903 World Series. You would think that someone along the line would at least check this stuff.

Actually, there probably is a core of truth to Kennedy’s story. SS Wagner did make two errors in the sixth inning of game 5 of the World Series, which was played in Pittsburgh. A third error was made by Fred Clarke, who played LF. According to Roger Abrams’ wonderful book on the 1903 World Series, a group of 100 Red Sox fans, known as the Royal Rooters, did travel to Pittsburgh from Boston by train for the four World Series games in Pittsburgh. They also made “Tessie” their theme song and sang it repeatedly. A special version, to be sung when Wagner came to the plate, went:

Honus, why do you hit so badly?

Take a back seat and sit down.

Honus, at bat you look so sadly

Hey, why don’t you get out of town.

Then the Rooters would stomp their feet three times in unison shouting “Bang Bang Bang.”

And then one more: “Why don’t you get out of town?”

This could easily be adapted to cover bad plays in the field as well.

Honey Fitz was by all accounts a great fan of the Red Sox and even once tried to buy the team. Abrams doesnt mention him as one of the Royal Rooters, but he probably was.

Whether the singing by Fitzgerald or the Rooters more generally bothered Wagner is an open question, but he did commit a series-high six errors and batted a disappointing .222 with only one extra-base hit. He also struck out to end the series.

Here are a few moments of upbeat hopefulness for those (count me in) who find keeping an eye on Milwaukee’s education scene to be pretty somber going much of the time.

Here are a few moments of upbeat hopefulness for those (count me in) who find keeping an eye on Milwaukee’s education scene to be pretty somber going much of the time.

Massachusetts Attorney General and unsuccessful U.S. Senate candidate Martha Coakley’s error in labeling Red Sox pitcher Curt Schilling a Yankee fan was reminiscent of the late Senator Ted Kennedy’s tenuous command of the world of baseball. Few can forget his

Massachusetts Attorney General and unsuccessful U.S. Senate candidate Martha Coakley’s error in labeling Red Sox pitcher Curt Schilling a Yankee fan was reminiscent of the late Senator Ted Kennedy’s tenuous command of the world of baseball. Few can forget his