Part Six of a Six Part series on Election Law, providing context to our system of government, our election process and a little history to evaluate and consider in the candidate-debate.

In an age where the presidential vote is relatively close, a two-party system dominates politics, and the average voter recognizes that voting for an independent/splinter candidate has no real shot at electoral success, is this really what the framers intended in 1787 when drafting the Constitution of the United States?

Doubtful.

Not only was the Electoral College system problematic almost from the moment it left the starting block, but the election process has grown more complicated, more winner-takes-all, and more divisive than perhaps the delegates could ever have imagined.

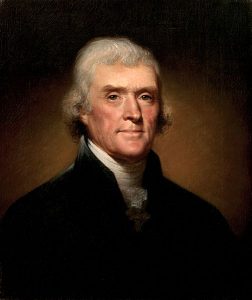

For instance, in 1797, Th omas Jefferson, the then-sitting Vice President, wrote a letter to his colleague, Edward Rutledge, in which Jefferson reported that the mood of the nation’s capital had become politically divisive:

omas Jefferson, the then-sitting Vice President, wrote a letter to his colleague, Edward Rutledge, in which Jefferson reported that the mood of the nation’s capital had become politically divisive:

“The passions are too high at present, to be cooled in our day. You & I have formerly seen warm debates and high political passions. But gentlemen of different politics would then speak to each other, & separate the business of the Senate from that of society. It is not so now. Men who have been intimate all their lives, cross the streets to avoid meeting, & turn their heads another way, lest they should be obliged to touch their hats. This may do for young men with whom passion is enjoyment. But it is afflicting to peaceable minds. Tranquility is the old man’s milk.” (Jefferson to Rutledge, June 24, 1797, in Jefferson, Papers, 29:456-57.)

Does Jefferson’s report of a political divide — in 1797! — sound familiar when looking at today’s election debate?

Keep in mind, Jefferson’s comments were less than a decade after the Constitutional Convention, with him reporting that the political divide was becoming personal even amongst elder-statesman.

Unlike fine wine, the divide did not get better with time. In the election of 1824, the Congressional caucus nominated Albert Gallatin for Vice-President. The caucus was attacked as undemocratic and Gallatin, the nominee, later withdrew his candidacy. The claims in that election, just as today, related to attacks on credibility, a candidate’s “fitness” for office, and the failure to obtain popular support.

Need more proof? Fifty years later, when Rutherford B. Hayes won the electoral vote, not popular vote in the election of 1876, many in the losing party referred to him as “Rutherfraud” B. Hayes or “His Fraudulency” during his 4-year term.

Now sitting over 100 years removed from Hayes, over 150-years removed from Gallatin, and over 200 years from Jefferson, the same familiar themes persist, with candidates — and parties — in a gridlock of attacks, issue-related and personal, that, if not on par with past history, certainly have some historical precedent.

The point being that for those who argue that this election cycle is the worst of all time, historical review in this and prior blog posts illuminates some evidence that this election cycle is not far removed from the ilk of elections-past.

At the same time, what prior blog-posts have attempted to do is bring this political-divide within the context of the Constitution of the United States.

In prior blog-posts, much of the authority and background can be found in Ray Raphael’s book Mr. President: How and Why the Founders Created a Chief Executive (2012). There, Mr. Raphael sums up the Constitutional Law debate that has morphed into countless laws, opinions, cases and legal jurisprudence that makes a horse run:

“The document the framers created was not some algorithm that could be dutifully followed to achieve optimum results. Instead, by necessity, it would have to be treated as an incomplete and therefor evolving guide that pointed in a general direction but left more room than some might prefer for interpretation–and, like it or not, discretion.”

Taken one step further, the interpretive and discretionary application of the Constitution forms the center-piece to the very-political fabric that holds court today, just as it did 200 years ago.

So what does all this mean in terms of today’s election cycle? I summarize it into three points.

First, like it or not, there is a process to our government. Process exists for an election. Process exists for enacting laws. Process exists in the courts. While criticism can be directed at failings within the process, there is a process, as debatable and imperfect as it may be, and it is this process that provides the baseline for citizen-rights — made possible by your right to vote.

Second, if you followed the winding path of my prior posts, the same point comes up again and again: compromise. Ours is a system of government made of compromise. Compromise exists today (albeit often begrudgingly), just as it did at the time of the Constitutional Convention (often begrudgingly). The framers themselves were not in agreement with everything in the Constitution — nor would you be expected to be in agreement with all positions or all sides when exercising your right to vote.

Third, and perhaps most important, disagreement is part of both the process and the compromised solution that underscores our American government.

On this last point, consider this election cycle, where the media or even your neighbor can be steadfast in beliefs over a cause, a principle, a candidate or a position — whether it be in law, or fact, or pounding the table — but that same zealousness is, by design, not reflective of all, or possibly not even a majority of the citizenry.

It is one view.

You can agree or disagree, be persuaded or not.

It is still one view.

And if Joe-voter wants to really reflect on the big-picture of government come election-time, remember that our government of process, compromise and disagreement (both perceived and actual) is perhaps best reflected in the Constitution’s system of checks and balances.

Indeed, what the framers did was devise a system that gave voice to those who agree, or disagree; the goal was not to unite on all points, but rather to unite on a general direction of government despite a difference in view.

I will give an example that ties together this point. Many a pundit has espoused the view that Joe-voter, in throwing his lot to any of the Presidential candidates, must take into account that the President-elect will have the opportunity to appoint one or more Justices on the Supreme Court of the United States, and thus, when connecting these dots, such appointment will send the Court on a particular ideological path for years to come.

Such a conclusion is based on a judge’s staying power where the federal judiciary sits for life and good behavior.

Without mentioning context, however, the forest can be lost through the trees. A candidate is nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate, meaning both branches are involved. A Justice is one of nine, so one-vote does not, by itself, decide a case. The Court’s themselves have checks, in procedure and role — only certain cases are decided by the Court as, by-law, federal courts are courts of limited jurisdiction. And, from at least an historical perspective, there are many examples of a Justice not voting along the party-line from which his/her nomination sourced.

Of course, there are counter-points to the forested argument, both in terms of voting and appointment, including the fact that, if we again tour history, governmental action and inaction can be difficult to overcome and a sitting-Justice’s decision is important — which is why the Supreme Court nomination process is appropriately discussed.

The point being that Joe-voter should take-to-heart that there is a bigger-picture story to be told. One person’s decision-making, regardless of branch, is part of a larger process of decision-making, and this is true in all facets of government, including the Supreme Court’s process for nomination, review and outcome.

(Even the court-system has a check within its own system, and if you adhere to the viewpoint that the appellate courts make the law, as opposed to the federal district courts, this acts as yet another balance to the nomination process.)

So, in summary, if Joe-voter were to come up to you and talk about dislike for the candidates or the election system as a whole, you can certainly agree or disagree — because that opinion may be right or wrong, based on fact or not, often more complex than simple — but I also encourage you to keep in mind, and discuss, the context to the right to vote, and an historical perspective to our government and elections past.

In this regard, Joe-voter can choose not to vote, yet, as I would tell him, nowhere can you enjoy your citizenship more than by exercising the Constitutional right to vote.

As begun in my first blog-post, there is no hiding a sense of voter apathy, disgust and lack of enthusiasm for a candidate or the process as a whole. As a society, we can debate how widespread and rampant such views have spread across the laity.

At the same time, our system of government does not require (or even want) you to check those feelings at the door come election time. Instead, the American-way, and in particular the right to vote, is to take on the weighty obligation of voting while fully embracing the views of others and your own positive and negative personal opinions.

This is how it was in 1787.

This election cycle is no different.

Which leads me to one final point when it comes to this election. A voter can be passionate or indifferent on this election, enthusiastic or uncaring on a candidate, optimistic or pessimistic on government, or many shades in between, but, regardless of position, know this: your vote is part of a grander plan, a greater scheme, and one important piece to the puzzle.

See you on Tuesday, November 8 — Election Day.

A special thank you to the Marquette University Law School faculty and administrators, and of course my legal brethren, for allowing me the opportunity to express my views and to work in a profession that, while challenging and often not easy, is both virtuous and rewarding when allowed the opportunity to voice beliefs within the rule of law.

Thank You for an excellent series on election law. You present the laborious, diligent and passionate process that gave birth to our election law in an understandable format. Providing specific examples in context gives the reader a clear understandable “picture” of election law and process. Links placed in the overview provide ample access to resources for those who need to “dig deeper”. This style makes the series accessible and informative to the widest range of readers.