In an earlier posting, Rick Esenberg expressed his opposition to recent George Soros-sponsored efforts to devise a plan to circumvent the operation of the Constitution’s venerable Electoral College.

In an earlier posting, Rick Esenberg expressed his opposition to recent George Soros-sponsored efforts to devise a plan to circumvent the operation of the Constitution’s venerable Electoral College.

The “problems” with the Electoral College are well-known. Its “winner-take-all” feature supposedly distorts the electoral process, and on four occasions (1824, 1876, 1888, and 2000), it has chosen a president who received fewer popular votes than one of his opponents.

Debates over the future of the Electoral College often assume that there are only two options: scrap the institution altogether or else accept that it will continue to operate as it has in the past. Scraping the Electoral College is usually assumed to require a constitutional amendment, although the Soros plan would actually leave the Constitution unchanged but seek to bind electors to cast their votes for the candidate with the largest national popular vote regardless of the results in their particular state.

There is an alternative, however, that would make the results of the Electoral College more democratic but would leave the Constitution unchanged.

Although it has long been the practice that individual states award their entire electoral vote allotment to the candidate receiving the largest number of popular votes in the state, there is no constitutional requirement that states follow this approach. In the first part of the 19th century, many states split their electoral votes, and today two states, Maine and Nebraska, have abandoned the “winner take all” rule. (In 2008, Nebraska split its electoral votes between McCain and Obama.)

In the first third of the 19th century the selection by a single state of electors supporting different candidates was a frequent feature of American presidential elections. As late as 1824, five of 24 states did just that. In 1828, three states did so, including New York, which cast 20 votes for Andrew Jackson and 16 for the incumbent John Quincy Adams. By the mid-1830’s, every state appears to have embraced the winner take all system, although in 1860, New Jersey reverted to the older system and ended up dividing its seven electors between the Republican Abraham Lincoln (4) and the Northern Democrat Stephen Douglas (3)

Article II of the United States Constitution makes it clear that each state has the power to adopt a different system of choosing electors, should it choose to do so. There are at least three ways that states could chose to apportion their electors that would produce more equitable allocations of electoral votes.

A state could simply apportion its electors on the basis of the popular vote. For example, in 2008, Wisconsin’s 10 electoral votes could have divided six for Obama and four for McCain based upon Obama’s 56% to 44% margin of victory. On the other hand, such a system can run into problem because of the presence of “third” parties. Like Wisconsin, Minnesota currently has 10 electoral votes. In 2008, Obama and McCain received 54% and 44% of the popular vote, respectively, with 2% going to third parties. The Constitution requires the appointment of actual electors, so it is not obvious as to whom the tenth Minnesota elector would be assigned.

A second possibility would be for a state legislature to divide the state into “electoral districts” with each district choosing one elector. Because each state has two more electors than it has representatives in Congress, congressional districts could not be used for this purpose. Instead, states would have to create special districts. Wisconsin, for example, would have to be divided into ten districts whose sole function would be the selection of presidential electors. Obviously, this could be done, but the process would involve many of the same difficulties that arise when the state has to redraw the lines of congressional districts.

The third possibility is the approach currently taken in Maine and Nebraska. The presidential candidate receiving the largest number of popular votes in each congressional district receives one elector, and the winner of the statewide popular vote is awarded an additional two electors. In Wisconsin in 2008, Obama received the largest number of popular votes in seven of the state’s eight Congressional Districts. Consequently, under the Maine/Nebraska system he would have received nine of the state’s ten electoral votes with the other vote going to McCain.

While this approach would have had only a slightly different effect in Wisconsin (where Obama received all ten electoral votes), there are other states where the impact would have been greater. In Ohio, for example, this system would have divided the state’s twenty electoral votes evenly between Obama and McCain instead of having all twenty go to Obama. Even in large states won easily by one candidate or the other, the losing candidate would have collected electoral votes. Under this system, McCain would have received eleven electoral votes in California and four in New York, while Obama would have received eleven votes in Texas and five in Georgia.

Obviously, the great advantage of this system is that it does not require the creation of additional electoral districts. It would also create an incentive for candidates to campaign in states even if they perceived that they had no real chance of winning the overall popular vote in that jurisdiction. On the other hand, it is also possible that this system might make third party candidacies more popular since it would not be necessary to carry entire states to have a presence in the Electoral College.

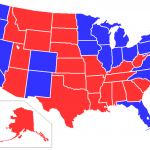

Had the Maine/Nebraska system been in effect in every state in 2008, the final result would have been a 301-237 victory for Barack Obama, compared to the actual margin of 365-173. Very few states under this system would have awarded all of their electoral votes to a single candidate. In fact, if we remove the eight jurisdictions with three electoral votes (where a divided vote was impossible), 32 of 43 jurisdictions would have divided their electoral votes. Of the eleven that would have voted unanimously, only four had more than five electoral votes, and only one (Massachusetts) had more than ten.

Although the allocation of electoral votes would have looked much different, the Maine/Nebraska system would not have produced a different result in any of the last three presidential elections (which are the only ones for which I have recalculated the vote). Obama would have won in 2008, although not by as large a margin. Earlier in the decade, the geographic dispersion of his supporters would have meant that George W. Bush would have twice been elected president under the district system. In fact, he would have won by even larger margins under this system than he did in 2000 and 2004, even though he received fewer popular votes than Al Gore in 2000. Under the Maine/Nebraska system, Bush would have defeated Gore in 2000 by a margin of 288-250 (rather than 271-266), and John Kerry in 2004 by 317-221 (instead of 286-252).

Even though the Maine/Nebraska system would not eliminate the possibility of a “minority” president, it would “decentralize” the electoral process and would better protect the rights of those who reside in less populous parts of the country to participate in the presidential election process in a meaningful way.

The challenge of course is to convince the other 48 states that it would be in their and the nation’s best interest to adopt the Maine/ Nebraska approach. Unless all states adopted the “district” approach, states retaining the winner-take-all system might actually become even more important. As critics of this approach have pointed out in the past, the original system of district elections disappeared in the early 19th century because of a perception that the winner-take-all states were able to exercise greater influence.

Of course, states could be required to adopt a district system, but that would require a constitutional amendment.

What follows is a state by state breakdown of electoral votes for the 2008 presidential election, had the Maine/Nebraska system been in effect in each state. The numbers following the name of each state are the electoral votes for Obama and McCain, respectively. In states marked with an * Barack Obama was the recipient of the largest number of popular votes.

2008 Results, Alternative Approach to Choosing Electors.

Alabama 1-8

Alaska 0-3

Arizona 2-8

Arkansas 0-6

*California 44-11

*Colorado 5-4

*Connecticut 7-0

*Delaware 3-0

*Florida 12-15

Georgia 5-10

*Hawaii 4-0

Idaho 0-4

*Illinois 18-3

*Indiana 5-6

*Iowa 6-1

Kansas 1-5

Kentucky 1-7

Louisiana 1-8

*Maine 4-0

*Maryland 8-2

*Massachusetts 12-0

*Michigan 14-3

*Minnesota 7-3

Mississippi 1-5

Missouri 3-8

Montana 0-3

Nebraska 1-4

*Nevada 4-1

*New Hampshire 4-0

*New Jersey 12-3

*New Mexico 4-1

*New York 27-4

*North Carolina 8-7

North Dakota 0-3

*Ohio 10-10

Oklahoma 0-7

*Oregon 6-1

*Pennsylvania.. 11-10

*Rhode Island 4-0

South Carolina 1-7

South Dakota 0-3

Tennessee 2-9

Texas 11-23

Utah 0-5

*Vermont 3-0

*Virginia 8-5

*Washington 9-2

West Virginia 0-5

*Wisconsin 9-1

Wyoming 0-3

District of Columbia 3-0

Presumably the DC election would be on a winner-take-all basis, as it is in other states with three electoral votes.

I am in Prof. Hylton’s American Constitutional History class this term, and nothing undermines ones’ affection for the Electoral College quite as much as learning why the Framers adopted it in the first place.

That aside, I am still not convinced that a simple, direct popular vote method is all that bad. Modern technology is making it actually easier to connect effectively and inexpensively with large numbers of voters. I am not convinced that candidates would stop campaigning in small population areas. A campaign stop in Sioux City could be broadcast throughout the nation (and even the world); making every public appearance useful in a nation-wide campaign regardless of where the appearance actually occurs. The internet makes it possible for a candidate to sit in their home in Springfield, IL and take questions from a Hawaiian who’s sitting on a beach; and for the rest of us to listen in. For these reasons, smart campaigns will pick the locations of their appearances for their symbolic value, not the population density. In the 21st century, our population is evenly dispersed because their connectedness is no longer dependent on where they live. Rapid City is as good a place to campaign as Greenwich Village or the Hollywood Hills.

The thing that really disturbs me about the idea that candidates might ignore the more dispersed population areas is the implicit assumption that the concerns of these areas are so different from urban areas that unless a candidate actually visits places like Bismarck, ND; they will be unable to understand the issues there. That may have been true in the 19th century, but it isn’t true now. In any event, no candidate can visit every place. There’s just not enough time.

There is no reason to hang on to the Electoral College except our fear of worst-case-scenarios, a fearthat can be used to justify resisting any change.

Dividing a state’s electoral votes by congressional district would magnify the worst features of the Electoral College system. What the country needs is a national popular vote to make every person’s vote equally important to presidential campaigns.

If the district approach were used nationally, it would less be less fair and less accurately reflect the will of the people than the current system. In 2004, Bush won 50.7% of the popular vote, but 59% of the districts. Although Bush lost the national popular vote in 2000, he won 55% of the country’s congressional districts.

The district approach would not cause presidential candidates to campaign in a particular state or focus the candidates’ attention to issues of concern to the state. Under the 48 state-by-state winner-take-all laws(whether applied to either districts or states), candidates have no reason to campaign in districts or states where they are comfortably ahead or hopelessly behind. In North Carolina, for example, there are only 2 districts the 13th with a 5% spread and the 2nd with an 8% spread) where the presidential race is competitive. In California, the presidential race is competitive in only 3 of the state’s 53 districts. Nationwide, there are only 55 “battleground” districts that are competitive in presidential elections. Under the present deplorable 48 state-level winner-take-all system, two-thirds of the states (including California and Texas) are ignored in presidential elections; however, seven-eighths of the nation’s congressional districts would be ignored if a district-level winner-take-all system were used nationally.

A national popular vote is the way to make every person’s vote equal and guarantee that the candidate who gets the most votes in all 50 states becomes President. The National Popular Vote bill would guarantee the Presidency to the candidate who receives the most popular votes in all 50 states (and DC). The National Popular Vote bill would take effect only when enacted, in identical form, by states possessing a majority of the electoral votes–that is, enough electoral votes to elect a President (270 of 538). When the bill is enacted in a group of states possessing 270 or more electoral votes, all of the electoral votes from those states would be awarded, as a bloc, to the presidential candidate who receives the most popular votes in all 50 states (and DC). This would guarantee the White House to the presidential candidate who receives the most popular votes in all 50 states (and DC).

See http://www.NationalPopularVote.com

Although I support the goals of nationalpopularvote.com; I am not confident the method is sound. Principally it relies on voluntary compliance; which might work for a time; but which eventually might break down in the face of a controversy with significant sectional overtones. What happens to the system if it is adopted and then later several major states drop out? What if they drop out between the election and the meeting of the Electoral College?

Constitutional challenges are likely to this kind of interstate compact, but also likely to fail (at least if the Court is fair; no longer a given).

If enough states can pass the act, then enough states can pass an amendment to eliminate the Electoral College permanently in favor of a popular vote system. Why go for a half-way measure, when a full solution is not that much harder?

To amend the Constitution 2/3 of the state legislatures must vote for the amendment. Getting 270 electoral votes doesn’t require (nearly?) such a high percentage of the states.

Interesting. In each of the last three cycles, this method would increase the electoral vote count of the GOP candidate. That is consistent with the idea that Democratic support is more geographically concentrated than support for Republicans. If that is so, then this plan would tend to favor Republicans and probably could not be enacted for that reason. Whether or not this would exacerbate or alleviate the potential for the electoral vote to deviate from the popular vote would, I suppose, depend. It could also could result in the election of the candidate who lost the electoral vote when the “winner take all” system would not or it could prevent that from occurring.

People forget that, while Bush lost the popular vote and won the electoral vote in 2000, John Kerry came very close to doing the same thing in 2004. Had he carried Ohio, rather than lose it by two percentage points, he’d have become the President. That’s a scenario in which this system would have prevented victory for a popular vote loser, but I can imagine the opposite scenario as well.

As the late Tip O’Neill was want to say, “All politics is local.” My take on the proper way to run the Electoral College is shaped the experiences of my native Congressional District, the 9th District of Virginia.

Many of the abuses cited in the above posts are the product of blatantly partisan efforts to create congressional districts that are geographically bizarre, but safely Democratic or Republican. Gerrymandering has always made a travesty of the political process, and the problem could be corrected by the embrace of a non-partisan procedure for drawing district lines in a way that makes geographic sense.

The Ninth District of Virginia has always been constructed along logical geographic lines. It starts at the far southwestern tip of Virginia and extends eastward and north until it encompasses the requisite number of people. Because of the lack of population growth in its region, it has gotten larger and larger over the years, but it boundaries have never been dramatically alterred for partisan purposes.

From the end of the Civil War until the 1960’s, the 9th District of Virginia frequently voted for Republican presidential candidates, but because the rest of Virginia was overwhelmingly Democratic, its votes never affected the outcome of the presidential race in the state. More recently, Virginia has become a Republican stronghold (2008 excepted), but at the same time the 9th District has more regularly voted Democratic, again, usually without effect.

For reasons of history, culture, and geography, the viewpoints and opinions of those who live in southwestern Virginia have frequently differed from those of the majority of their fellow Virginians.

There is no reason why their voices (and votes) should not count when it comes to electing a president. Under the Maine/Nebraska system, they would count.

I don’t think that one can really know the effect of Professor Hylton’s idea by looking back at previous elections, because the parties were playing by the rules of the current system.

One doesn’t know how many Democrats might have turned out in Georgia, or Republicans in California, until it actually counts. This is why the results look so lopsided.

I believe that the present electoral college system increases the perception of a red/blue state divide. Even in the reddest of red, and the bluest of blue states, at least 40, and more likely 45% of the voters lean towards the other party. In a truly national election or one where the parties know a couple of electors can be swung there way, the parties will be forced to run a true national campaign.

And maybe sometime in the future, candidates who speak to the national interest rather than the bases of their parties will be nominated and even win a presidential election.

A state legislature cannot, under either the current system or the National Popular Vote plan, change the state’s method of awarding its electoral votes during the five-week period between the day when the people cast their votes for President in early November and the day when the Electoral College meets in mid-December. However, if anyone is concerned about this kind of hypothetical post-election maneuver, the National Popular Vote bill offers even more protection against post-election mischief than the current system does.

Almost all compacts that permit withdrawal impose a delay on the effective date of any withdrawal. The reason for the delay is that almost all compacts contain obligations that a member state would never have acknowledged to unless it could rely on the enforceability of the obligations undertaken by the other states that are party to the compact. Each member state must have time (and sometimes other types of compensation) to adjust its behavior if another state desires to withdraw.

Thus, the National Popular Vote compact imposes a delay on the effectiveness of any withdrawal. Clause 2 of article IV of the National Popular Vote compact provides:

“Any member state may withdraw from this agreement, except that a withdrawal occurring six months or less before the end of a President’s term shall not become effective until a President or Vice President shall have been qualified to serve the next term.”

That is, no withdrawal from the National Popular Vote compact can become effective between July 20 of a presidential election year and the inauguration on January 20 of the following year. This six-month “blackout” period was chosen because it encompasses six important events relating to presidential elections, namely, the national nominating conventions, the fall general-election campaign period, Election Day on the Tuesday after the first Monday in November, the meeting of the Electoral College on the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December, the counting of the electoral votes by Congress on January 6, and the inauguration of the President and Vice President for the new term on January 20.

Although it is true that a state legislature may not, by an ordinary statute, bind the hands of a future legislature, an interstate compact does bind future legislatures until such time as the state withdraws from the compact in accordance with the compact’s terms. In fact, an interstate compact is among the few ways to tie the hands of a future state legislature. The reason is that an interstate compact is a contract. Withdrawal from any contract may only be made in accordance with the contract’s own terms. It is settled law that, once passed, an interstate compact takes precedence over all existing or future state laws until a state withdraws from the compact under the terms provided in the compact. The reason that the state legislature is bound to the terms of an interstate compact is the Impairments Clause of the U.S. Constitution (article I, section 10, clause 1):

“No State shall … pass any … Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts.”

Any attempt by a state to pull out of the compact in violation of its terms would violate the Impairments Clause of the U.S. Constitution and would be void. Such an attempt would also violate existing federal law. Compliance would be enforced by Federal court action.

see http://nationalpopularvote.com/pages/answers.php

The process for amending the U.S. Constitution does not reflect the will of the people. A federal constitutional amendment favored by states containing 97% of the people of the U.S. could be blocked by states containing 3% of the people.

The National Popular Vote bill is not an “end run” around the Constitution. The U.S. Supreme Court has repeatedly characterized the authority of the states over the manner of awarding their electoral votes as “exclusive” and “plenary.”

The winner-take-all rule currently used by 48 or the 50 states is not in the U.S. Constitution. The winner-take-all rule was used by only 3 states in the nation’s first presidential election in 1789. Our present-day system was neither specified by the Constitution nor favored by the Founding Fathers.

The congressional district allocation of electoral votes that is currently used by Maine and Nebraska is not in the U.S. Constitution. No state used that system in 1789.

States can, and frequently have, changed their method of awarding electoral votes over the years. All the U.S. Constitution says is “Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors . . .”

Since the Constitution was enacted by the people, and the amendment process is specified in the Constitution, the amendment process does reflect the will of the people. The process is intentionally difficult to prevent temporary passions leading people to make fundamental changes.

A popular election system for the presidency is my preference, but the Maine/Nebraska system is a good option; it preserves the possibility of outlier-counties (such as Prof. Hylton’s 9th Virginia) making a difference.

As for Prof. Esenberg’s comments, since I am an independent, the comparative effects on the two major parties are not only speculative, but of no concern to me. More importantly, if electoral college votes are allocated differently, this is likely to change how voters behave; past behavior is not a reliable guide to future behavior if the system itself is changed.

I should have added that one of the great appeals of the Maine/Nebraska approach to reforming the Electoral College is that it can be done on a state-by-state basis and is perfectly consistent with the Constitution as written. Maine and Nebraska have already proven that it can be done, and in the past election, the residents of Nebraska’s Second District saw their votes count when they would not have had Nebraska followed the winner-take-all system.

All the other proposals require either a constitutional amendment or the resort to constitutional chicanery.

The Greens and Libertarians might get an electoral vote in Maine or Nebraska, more likely the Libertarian Party in Nebraska, and in Maine the few Republicans might vote Green to stop Obama from getting them all.

If the electoral college can’t end a deadlock, the House next year will obviously choose Romney, but the Senate could possibly pick Cheri Honkala. In South Korea an impoverished child became one of the Presidents and we still hear stories of a once-impoverished Hitler who actually squandered his inheritance before becoming poor.

I believe Gerald Ford would have won the 1976 election under the Maine/Nebraska system, even though Carter won an absolute majority of the popular vote. Please focus on the 1976 election for further research.

Why? Democrats get a disproportionate number of votes from urban districts where they get 80 or 90% of the votes. They can carry some very large states that way. The Maine/Nebraska system neutralizes that strategy.

George Bogdan is right that the results of the 1976 Presidential Election, in which Jimmy Carter defeated Gerald Ford 297-241, would have been much closer under the Maine/Nebraska system.

However, Carter would still have prevailed, although by the incredibly thin margin of 270-268. Ford’s biggest gain was in New York state in which he lost the popular vote and all 41 electoral votes in the actual election. However, Ford actually carried 23 of the state’s 39 congressional districts, so under the proposed alternative he would have outpointed Carter in electoral votes, 23 to 18.

At the time I wrote this blogpost, I was unaware that the noted statistician Jeff Sagarin had a similar interest in the Maine/Nebraska alternative.

Jeff’s application of the Maine/Nebraska system applied to the results of all presidential elections from 1968 to 2000, can be found at http://sagarin.com/sports/electoral.htm. His research clearly exceeds my own.

As most people know, Jeff is one of the most renowned sports statisticians in the United States. His work pioneered the use of computers to perform evaluations of relative strength among college and professional teams.

I agree that the Maine/Nebraska plan would not have changed any results to any past elections but that it would have been more accurate in the amounts of Electoral College(EC) votes that were counted.

The EC is based on 435 voting members of HR, 100 Senators, and 3 delegates from DC. So why shouldn’t the EC that is counted, be based on the votes cast in all 435 districts and by the representative parties elected for each senator, plus 3 winner take all for DC.

Currently, I live in Illinois where I don’t think my vote for POTUS counts. Because it is a winner take all state. We don’t even get statistics for POTUS election results by congressional districts. We get county results, but because of Republican and Democratic gerrymandering, it is really difficult to get accurate congressional district counts.

I would hope that sometime in the near future that our representative leaders would do away with gerrymandering for all of the US. Use county/parish lines and representative population from each census in order to coordinate representatives for each state, for the US Congress and the Electoral College.

The National Popular Vote interstate compact law (not currently in effect) was approved in Illinois. If a state has agreed to this law, then any candidate that loses the election but wins the popular vote, must vote with all the EC votes. For example, if Trump had more popular votes in Illinois but Clinton had more national popular votes in 2016 election, then Illinois must vote all EC votes for Clinton, if this law was in effect.

Thank goodness there are only 10 states that have agreed to this, but what if 10 more large EC states approve this as state law. Then the 12th Amendment of the US Constitution has been effectively repealed. This is why I believe this law should be repealed in Illinois and other states.

I’m just doing research — trying to get a handle on the Electoral College issue. What exactly is the problem with the first option? It’s the closest representation to the popular vote: just award the electors in direct relation to the vote. No amendments are necessary that I can see. In regards to third-party concerns, why can’t each state require a minimum % of the vote in order to qualify for electors?

Thank you to all who have chimed in over the past 14 years, as I’ve enjoyed reading your different perspectives about the electoral college. In particular, the “Maine/Nebraska” approach interested me the most as I have never really though about this implemented nationally. I am a high school history teacher and, similarly to Michael before me, I am conducting research on this topic, although specifically on the Election of 1824 and the “corrupt bargain” that Jackson claimed to have taken place, leading to his loss. So, I will post this question out there—what would the US Presidential Election of 1824 have yielded if all 25 states at the time used it?

In 1824 the “winner-take-all” electoral points system was used in every state except Delaware, Louisiana, New York, Illinois and Maryland. These 5 states used this “district” proportional vote approach, very much like Maine and Nebraska use today. And Jackson won the majority of “electoral points” in Maryland, Illinois and Louisiana, but lost the popular vote in both Maryland and Illinois. I cannot find the breakdown of percentage of votes for Louisiana so I don’t know how Jackson would have done there. With Jackson receiving 3 of the 5 electoral points in Louisiana I can assume that it was close. I don’t know.

It is worth mentioning that I am very aware why most all states today use the winner-take-all electoral college system and how we’ve moved away from the founders model of a “district” proportional based voting system. The tipping point was the election of 1824 for presidential electoral systems, as twice as many states used the winner-take-all statewide method as used the state legislature method. The defeated Andrew Jackson even joined James Madison’s pleas for a constitutional amendment requiring a uniform district election system, but to no avail. This can’t help but make me wonder.

To anyone who is reading…my question again is: what would the results of the election of 1824 have been if the Maine/Nebraska “district” electoral college points system were used by all 25 states at the time?

I vote for a system we’re the state vote winner gets the 2 electoral votes allocated for the states Senators, then ditch the district vote count for the balance of the electoral state count to be divided between the 2 top vote counts on a percentage bases .

The winner take all system disenfranchises whatever party has a minority in each state, where in theory somehow this wrong should be corrected by the system as it all “evens out” as the national electoral count is tallied. However, this clearly has failed in history, when various Presidents were elected without a popular majority. Here is the real deal: universal suffrage was not part of US founding, and all of the efforts to expand voting rights scaled up almost insurmountable barriers put up by white supremists, who have been aided by various Supreme Court decisions (at least until 1965, but even recently as well). In Texas, we have no prayer of getting apportionment of electoral college electors passed, as it will be resisted by the Repub majority. No Dem has won here in so long, the Repubs know that a lot of Dems have quit voting in national elections, given the feeling that their Presidential vote never counts, and this aids in perpetuating this systemic wrong. The only way to really correct this bad system is to go to national popular elections.