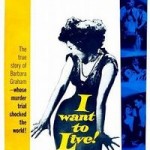

American cinema of the last century includes a large number of films with major characters on death row. James Hogan’s silent film “Capital Punishment,” for example, screened in 1925. During the 1950s, the death penalty was at the forefront in such respected films as Fritz Lang’s “Beyond a Reasonable Doubt” (1956), Robert Wise’s “I Want to Live” (1958), and Howard Koch’s “The Last Mile” (1959). The late 1990s and the first decade of the twenty-first century saw an even greater number of films inviting contemplation of the death penalty.

American cinema of the last century includes a large number of films with major characters on death row. James Hogan’s silent film “Capital Punishment,” for example, screened in 1925. During the 1950s, the death penalty was at the forefront in such respected films as Fritz Lang’s “Beyond a Reasonable Doubt” (1956), Robert Wise’s “I Want to Live” (1958), and Howard Koch’s “The Last Mile” (1959). The late 1990s and the first decade of the twenty-first century saw an even greater number of films inviting contemplation of the death penalty.

The latter flurry of films perhaps relates to the period’s especially pronounced campaign to end capital punishment. In keeping with the often-heard assertion that Hollywood leans to the left politically, most of these films seem opposed to the death penalty. Some express their opposition in the fashion of a “message film,” while others proffer more subtle dramatic narratives.

Despite their abundance and general tendencies, however, these films from the turn of the twenty-first century are, if subjected to more careful scrutiny, surprisingly ineffective cinematic expressions of opposition to the death penalty. “Dead Man Walking” (1995), the most acclaimed of the films, includes superb performances by Sean Penn and Susan Sarandon but is disappointingly ambivalent about capital punishment. Other films such as “The Chamber” (1996), “Last Dance” (1996), “A Letter from Death Row” (1998), “True Crime” (1999), and “The Life of David Gale” (2003) invite viewers’ sympathy for those sentenced to death by suggesting they were wrongfully convicted and sentenced in the first place.

As a result, the films stop short of truly indicting the hateful practice of capital punishment and of insisting all those facing death at the hands of a vengeful state should be spared. The films do not grow out of a deep and profound love of humankind, surely the most powerful basis for opposition to the death penalty. Despite their apparently progressive alignment, the films have been of little help in the campaign to end capital punishment once and for all.

I’m not sure I agree that films whose protagonist is an innocent person on Death Row are “ineffective cinematic expressions” of opposition to the death penalty. The roots of Illinois’ moratorium on the death penalty, for instance, took hold not in an idealistic love of humankind, but from the repugnance of getting it wrong on at least some occasions. If those are motivations which drive at least some real-world rejections of the death penalty, how is it ineffective when dramatized for the screen?

Additionally, the argument could be made that this appeal to the desire for justice for the wrongly convicted is merely a first step; if one can get a majority of people comfortable with the idea of indefinite moratoriums on executions, regardless of the reason, then it paves the way for outright abolition later on. Whether that road is fast enough or absolute enough for an individual’s tastes is a different issue from whether the appeal itself is effective, isn’t it?

I don’t know if “a deep and profound love of humankind” is a workable, persuasive argument to those people who might not already agree. The same argument could be applied to eliminating the armed forces and never waging war, which could also be seen as “facing death at the hands of a vengeful state”. Unless you’re addressing a roomful of conscientious objectors, or another population already predisposed to agreeing with your central argument, I don’t see it carrying the day. On the other hand, even people who don’t care much for the lives of criminals might be persuaded that we shouldn’t lump innocents in with the guilty on death row, and if we can’t avoid that outcome, best to avoid the whole trouble.

Thanks for this interesting post, David.

Another group of films seems to endorse capital punishment, but in a private sector way. In films such as “Death Wish” (1974) and “The Outlaw Josey Wales” (1976), family men whose loved ones are murdered turn to vigilantism to settle the score. In these films, only lethal vengeance seems to satisfy the requirements of justice.

There are many contexts in which private actors have more (and probably should have more) freedom to act than public officials, but the use of violence on other people is not generally regarded as one of those contexts. One possible exception is in states with a “Make My Day Law,” which permits the use of deadly force to defend against a violent attack or threatened violent attack in one’s home.

The phrase “make my day” in this context was popularized in “Sudden Impact” (1983), in which police officer Harry Callahan invites a criminal to threaten lethal force so that lethal force can be lawfully used against him.

Mike,

Thank you for your comment. Yes, a troubling number of Hollywood films lionize private parties who take jutice into their own hands and kill somebody. In addition to classic westerns and the Dirty Harry series, there’s D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915). It was a box-office smash and is often mentioned as the first truly accomplished feature-length film. It also endorses vigilante violence at the hands of the Klan. When I think of all these very popular films, I have to pause before saying a belief in the rule of law is a central part of the dominant ideology.

Peter,

I think the campaign for a death penalty moratorium in Illinois can be distinguished from a Hollywood film. The former showed the malfunctioning of the Illinois criminal system and, thank goodness, spared a number of innocent parties. Hollywood films, by contrast, are made primarily for entertainment and are profit-driven. Most are also character-driven. By casting someone as unfairly sentenced to death, Hollywood creates a more appealing protagonist. This standard approach, meanwhile, does not in my opinion take much of a stand against the death penalty. And, by the way, I would in fact like to see an end to war . . . .

David Papke

There are cases, of course, where the death penalty equals justice and where we can find the benefit from it.

For example, Dead Man Walking makes it quite clear that the murderer never would have repented and been truthful had he not faced the death penalty.

The greatest of all gifts,for the religious, may have been the outcome – salvation.

St. Thomas Aquinas: “The fact that the evil, as long as they live, can be corrected from their errors does not prohibit the fact that they may be justly executed, for the danger which threatens from their way of life is greater and more certain than the good which may be expected from their improvement. They also have at that critical point of death the opportunity to be converted to God through repentance. And if they are so stubborn that even at the point of death their heart does not draw back from evil, it is possible to make a highly probable judgement that they would never come away from evil to the right use of their powers.” Summa Contra Gentiles, Book III, 146.

Saint Augustine confirms that ” . . . inflicting capital punishment . . . protects those who are undergoing capital punishment from the harm they may suffer . . . through increased sinning which might continue if their life went on.” (On the Lord’s Sermon, 1.20.63-64.)

Saint Thomas Aquinas finds that ” . . . the death inflicted by the judge profits the sinner, if he be converted, unto the expiation of his crime; and, if he be not converted, it profits so as to put an end to the sin, because the sinner is thus deprived of the power to sin anymore.” (Summa Theologica, II-II, 25, 6 ad 2.)