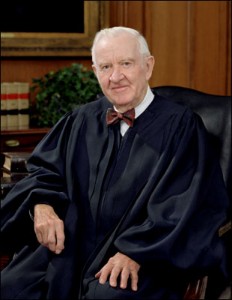

After he retired in 2010, John Paul Stevens published Five Chiefs: A Supreme Court Memoir. After a brief description of the first twelve Chief Justices of the United States Supreme Court, from John Jay through Harlan Fiske Stone, he describes in more detail the last five with whom he was professionally acquainted. Stevens clerked for Wiley Rutledge, after earning the highest GPA in the history of Northwestern Law School, during the 1947 – 48 Term when Fred Vinson was Chief Justice. Stevens was in private practice in Chicago, sometimes teaching antitrust law at the University of Chicago, when Earl Warren presided over the Court. It was during this time, however, that he argued his only case before the Court. In Five Chiefs, he notes that the most memorable aspect of his experience as an advocate before the Court was the sheer proximity of the Justices. Though the distance between the lawyer and the bench is over six feet, Stevens felt sure that “Chief Justice Warren could have shaken my hand had he wished.”

After he retired in 2010, John Paul Stevens published Five Chiefs: A Supreme Court Memoir. After a brief description of the first twelve Chief Justices of the United States Supreme Court, from John Jay through Harlan Fiske Stone, he describes in more detail the last five with whom he was professionally acquainted. Stevens clerked for Wiley Rutledge, after earning the highest GPA in the history of Northwestern Law School, during the 1947 – 48 Term when Fred Vinson was Chief Justice. Stevens was in private practice in Chicago, sometimes teaching antitrust law at the University of Chicago, when Earl Warren presided over the Court. It was during this time, however, that he argued his only case before the Court. In Five Chiefs, he notes that the most memorable aspect of his experience as an advocate before the Court was the sheer proximity of the Justices. Though the distance between the lawyer and the bench is over six feet, Stevens felt sure that “Chief Justice Warren could have shaken my hand had he wished.”

Details like this provide an inside glimpse of the Court. Early in his account, Stevens describes how the prohibition against playing basketball in the gym directly above the courtroom occurred during Vinson’s tenure: Byron White, one of Vinson’s first clerks and a former All-American, was practicing layups during oral argument. Stevens’ anecdotes are always respectful of their subjects and strike one as rather tame, at least until one realizes that civility, the ability to “disagree without being disagreeable,” is of the utmost importance to him. Stevens sat beside Antonin Scalia for much of his time on the Court and was the “beneficiary of [Scalia’s] wonderfully spontaneous sense of humor.” The year Scalia was appointed, they heard two cases involving police questioning of rather unsophisticated suspects. (Stevens does not identify the cases by name, another instance of his tact, but they are readily identifiable from his brief description of the facts as Colorado v. Spring and Connecticut v. Barrett, both decided in 1987). Scalia apparently leaned over and whispered to Stevens that it must be “dumb defendant day.” Now, anyone who has read a Scalia opinion knows that this cannot be the apogee of his wit and can be fairly certain that, in their twenty-four years on the bench together, he made sharper comments in the course of their duties.

One gets the sense that Stevens is reluctant to write anything that might reflect poorly on the Court or its Justices. And it is perfectly understandable that he would be unwilling to besmirch the institution with idle gossip. The Court is both a vital force and symbol of American democracy and, in the words of his dissent in Texas v. Johnson (1989), where the majority held that burning an American flag at a demonstration was protected by the First Amendment, it is “worthy of protection from unnecessary desecration.”

Nevertheless, Stevens does not shy away from criticizing his colleagues and even President Reagan when their decisions diverge from his closely held principles. Though he found common ground with Chief Justice Rehnquist on issues involving separation of powers, Stevens was sharply critical of Rehnquist’s stance on state sovereign immunity, particularly in Seminole Tribe of Florida v. Florida (1996). “Like the gold stripes on his robe, Chief Justice Rehnquist’s writing about sovereignty was ostentatious and more reflective of the ancient British monarchy than our modern republic.” Invariably, however, Stevens’ criticisms are based on what he considers to be flawed reasoning and not personal animus. His disapproval of Rehnquist’s decision to adorn his robe with gold stripes does not detract from his admiration for Rehnquist’s other fine qualities: his impartiality in both private conference and open court and his efficient administration of the Court’s business.

Stevens’ evaluation of the current Chief Justice, John Roberts, is very favorable. He describes him as “a better presiding officer than both of his immediate predecessors” as well as a more skilled representative of the Court in non-judicial settings. He is particularly appreciative of Roberts’ concurrence in Graham v. Florida (2010) because it represents for him a rejection of the interpretive approach that looks at the “original intent” of the Framers in determining the constitutionality of a given case. In Graham, Roberts agreed with the majority that imposing a life sentence on a juvenile defendant for a non-homicide offense violated the Eighth Amendment but rejected a categorical bar to such a sentence on the grounds that courts should weigh factors like the offender’s age and criminal conduct on a case-by-case basis. Roberts recognized a proportionality requirement at variance with Scalia’s dissenting opinion in Harmelin v. Michigan (1991) that would prohibit certain, specific punishments under the Eight Amendment but would not require, in Stevens’ words, “that the punishment fit the crime.”

Stevens’ discussion of Roberts’ opinion in Graham highlights two themes of his own judicial philosophy. According to Stevens, judges and justices should exercise restraint, and decide only what a case “actually presented” without trying “to craft an all-encompassing rule for the future.” Kyllo v. United States (2001) (dissenting). This, of course, stems in part from his understanding of the separation of powers in our system of government. As he wrote in Kyllo, Congress is the branch that “grapple[s] with. . . emerging issues” and it is counterproductive to “shackle them with prematurely devised constitutional constraints.”

Secondly, Stevens disagrees with an uncompromising insistence on the specific intent of the Framers because it does a disservice to the emerging problems of a changing society. Which is not to say the principles enshrined in the Constitution are readily susceptible to modification; if they were they would not be principles. Rather, it is that the strength of the principles lies in their flexibility and not in a code-like rigidity. Stevens quotes Justice McKenna in Weems v. United States (1910), “[A] principle, to be vital, must be capable of wider application than the mischief which gave it birth.”

These two aspects of Stevens’ jurisprudence help explain what comes across in his memoir: a reticence that displays itself in distaste for superfluous gossip on the one hand, and a generosity of spirit capable of disagreement without rancor on the other. Towards the end of Five Chiefs, Stevens writes that he has “no memory of any member of the Court raising his or her voice.” Whether this is strictly true, and as far as it is his memory there is no reason to doubt that it is, it sheds light on how Stevens envisioned the work of the Court as a civil pursuit for justice.

Justice Stevens on the Colbert Report (h/t Professor Idleman):

http://lawprofessors.typepad.com/conlaw/2012/01/justice-stevens-on-colbert-report-on-citizens-united-et-al-.html