An edited version of this piece appeared in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel on December 30, 2021.

Fort McCoy — Write down every detail of what happened to you in Afghanistan that makes you want to never go back. Write down everything you remember.

“I don’t want to remember,” the young woman said matter-of-factly in English.

For this, you have to remember, said Malin Ehrsam, one of two Marquette University Law School students on the other side of a table. Then, when you are done, you can forget.

For the Afghan “guests,” as they are officially called, remembering is crucial – remembering the threats, the fear, the deaths or torture of relatives, the ominous daily events, the abrupt and chaotic flight about four months ago from Afghanistan, where the government had collapsed and the Taliban had taken over. After various stops, the journey brought about 13,000 of them to Fort McCoy, a military base near Tomah in central Wisconsin.

Remembering those things is a key to persuading American officials to let them make the United States their permanent home. A second key to reaching that goal is navigating the lengthy and detailed process of seeking asylum or other legal status that will allow that to happen.

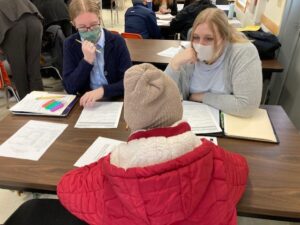

In a non-descript building in the middle of what amounts to a small city on the Fort McCoy grounds , Afghan guests have been meeting on weekdays with lawyers and law students, to start the asylum process.

Many of the volunteers in recent days have been Marquette Law School students. More than 50 signed up to spend most of a week between semesters and in this holiday season working in a legal clinic that is part of what Fort McCoy is offering its guests. That’s about 10% of the Marquette’s law school enrollment. The students are getting no pay and no academic credit. One group went to Fort McCoy the week of Dec. 13 and one group the week of Dec. 20. A third group is scheduled to go in early January.

Before they met with the Afghan citizens, the students received several hours of training. During the session I observed, they were asked why they were there.

“A lot of people need help,” one said. Another said, “I felt there was something I could do.” One said he wanted to “help out people in need and welcome them to the country.” And a fourth said that her family had friends who had been persecuted in a different country before gaining asylum in the US. “I’m here for them,” she said.

Grant Sovern, an immigration attorney with the Quarles & Brady law firm in Madison, has volunteered extensively at Fort McCoy and was one of the trainers. “Your job is to give people information and tools for moving forward,” he said. “We’re going to help them learn about the asylum process.”

Filling out the actual applications will come later, after the Afghan people move to a community where they will have a fixed address. They can’t apply for asylum using Fort McCoy as their address. For now, they have been granted emergency permission to stay in the United States while they pursue long-term permission.

They are being placed around the US at a steady pace. Fewer than 8,000 remain at Fort McCoy, the students were told. Two of the dozen or so people who met with students the day I observed were scheduled to leave by the end of that week, one for Milwaukee and one for Arizona. Both were members of the Hazara ethnic group that has been persecuted by the Taliban.

The law students were told that their work with the Afghans will help prepare them for going through the immigration process and, based on the draft paperwork to be filled out in these sessions, help the lawyers who will be assigned to each person after they reach their new home.

The students were told to expect some of the conversations to be emotional. In this group, the talk was mostly businesslike. The Afghans appeared to be prepared for taking part in a process that they knew was necessary.

But the stories were powerful. One person – the rules for reporting on the session call for not identifying people — said that she had a brother who was kidnapped. When the family couldn’t meet a ransom demand, the brother was killed and his body burned. She has a photo to prove it.

Another described how she and some of her siblings were now in different places around the world. She teared up only when she said her mother remained in Afghanistan.

Several of the Afghan people had worked for or alongside American troops or with American non-military organziations. Being associated with Americans in Afghanistan makes a person more likely to face Taliban reprisals and more likely to be granted asylum in the US.

Women applicants were encouraged to describe how their request for asylum is impacted by their concerns about the severe way the Taliban treat women. One of the law students stood up at the end of a length session and said she would never agree to be allowed out of her house only in the company of a male member of her family. Some of the Afghan women clearly agreed.

But before people got to their personal stories, they waded into the paperwork. The form for applying for asylum is 13 pages long. The first four pages offer numerous and detailed questions about the applicant’s background, family members, past addresses, past jobs, and more. Guests and law students spent much of a 2 ½ hour session going through the questions, filling in answers and looking at which of many required documents people did or did not have. Some of the guests brought along important papers such as birth certificates, marriage licenses and passports. Some did not possess much documentation. Some had electronic versions of such papers on smart phones. Some would need to file affidavits saying they didn’t have all the required documents.

When attention turned to how to write the statements about why the people wanted asylum, several of the guests needed coaching and encouragement. The law students were given suggestions for prompts that might help. Among them: “I first felt afraid when . . . .“ “I got on the plane because . . . .” and “What will happen to you if you return?”

Some dignitaries stopped to offer encouragement, one from the US State Department and two from the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, which has been involved in arranging for services for the Afghan guests, including the legal clinic volunteers.

The State Department official told the law students how much difference they could make for people, just by listening to their stories. Years from now, she said, you probably won’t remember each conversation.

But the people you help will still remember you and how you helped them start new and safer lives.