[This is the fourth in series of posts summarizing my new article, “The Grapes of Roth.”]

Introduction

Part I-A: Duck-Rabbits in Equity

Part I-B: Counting to 21 Similarities

By the mid-1970s judges in both the Second and Ninth Circuits realized that the “recognizability” standard for copyright infringement determinations was unworkable. As Roth Greeting Cards and International Luggage Registry had demonstrated, mere recognizability swept uncopyrightable as well as copyrightable material into the comparison, and hinged the infringement determination on the faintest suggestion of either. Some test was needed that would allow courts to do all three parts of the difficult balancing act described in Part I-A, in particular the assessment of how much protectable material was taken and whether that amount surpassed some threshold that made it unreasonable. Pre-Legal-Process courts had tackled these questions, but without saying much more than that the defendant had “wrongfully appropriated” the plaintiff’s protected expression, or taken its “aesthetic appeal,” or “justified” an infringement claim. Such openly normative assessments, relying on the judge’s subjective evaluation of the material taken, plainly would not do in a more formalist age. An alternative framework was needed.

Two decisions in rapid succession, one from the Second Circuit and one from the Ninth, latched onto the “total concept and feel” phrase as a way to express an overall level of similarity or dissimilarity in protected expression without openly making a normative or aesthetic judgement. In Reyher v. Children’s Television Workshop (2d Cir. 1976), the Second Circuit considered a claim by the authors of a children’s book based on a simple story: a lost child describes her mother only as “the most beautiful woman in the world,” which delays finding her because the mother does not meet conventional expectations of beauty. Sesame Street Magazine published a 2-page story that followed the same basic plot, but had different dialog, different illustrations, and was set in a different location. Was it infringing? Certainly the story was recognizable, but in almost every other detail the works were completely different. Reaching for a way to assess the protected expression in the stories holistically, the panel fell upon the empty verbiage from Roth: Given the simplicity of the stories, the court suggested, “we might [also] properly consider the ‘total concept and feel’ of the works in question.” Aside from a similar sequence of events, which the court found to be unprotectable scènes à faire, the remainder of the stories had an entirely different “total feel,” and thus there was no infringement.

The following year, the Ninth Circuit found its way back to the Roth formulation as well. In Sid & Marty Krofft Television Productions, Inc. v. McDonald’s Corp., the plaintiffs claimed that their children’s television show, “H.R. Pufnstuff,” had been ripped off to make the McDonaldland characters — Grimace, the Hamburgler, Mayor McCheese, etc. The issues were whether the jury verdict of infringement was correct and whether damages had been properly determined. But the opinion started with a long discussion of the proper test for infringement, casting shade — without mentioning any names — on how it had been done up to that point. Merely asking about the similarity between two works — in other words, whether anything from the plaintiff’s work is recognizable in the defendant’s — produces “some untenable results,” the court noted. “Clearly the scope of copyright protection does not go this far. A limiting principle is needed,” namely one that separates out idea from expression and determines only the extent to which there has been copying of the latter.

The court then grandiosely declared, “The test for infringement therefore has been given a new dimension.” Unfortunately, as is well known, that new dimension was a thorough garbling of the Arnstein v. Porter decision from the Second Circuit, a misstep that has thrown Ninth Circuit caselaw for a loop it is still trying to recover from. But after mangling the concept of substantial similarity, the Ninth Circuit had to apply its new framework to the jury verdict below, which had held the McDonald’s characters to infringe the somewhat similar-looking H.R. Pufnstuf characters. Were they? The Ninth Circuit panel agreed with the jury. “It is clear to us that defendants’ works are substantially similar to plaintiffs’.” Why? “They have captured the ‘total concept and feel’ of the Pufnstuf show.”

In both Reyher and Sid & Marty Krofft, the reference to “total concept and feel” allowed the court to express a conclusion as to whether the defendants had taken too much copyrightable expression without specifically identifying what in the plaintiff’s work was expression, what in the defendant’s work was similar or dissimilar, and where the threshold level of similarity lay. “Total concept and feel” was thus a way of summing up all three of the difficult judgments an infringement determination required, and it did so in a way that met modern judicial norms while avoiding the ham-handedness of “recognizability.”

The Reyher and Sid & Marty Krofft decisions, one finding infringement and the other finding noninfringement, well illustrated the advantages the new standard had. First, it provided judges with far more flexibility to reject infringement claims, based on the works’ lack of shared vibe, than the “recognizabilty” standard from Bradbury or Fab-Lu appeared to allow. “Recognizability” was easily satisfied even if the similarities were entirely unprotected, but “total concept and feel” allowed courts to claim that, despite “random similarities,” some required level of overall similarity was lacking. Courts also sometimes used “total concept and feel” to reject defense arguments based on numerous discrepancies, where the judges, examining the works themselves, found a pervasive similarity in expression.

But there was a second advantage, which was that “total concept and feel” was more in tune with modern judicial norms. If it was simply a flexible standard courts needed, they already had several available. Earlier decisions had defined infringement as copying that amounted to “wrongful appropriation,” or copying extensive enough that the ordinary observer would “regard [the works’] aesthetic appeal as the same,” or copying that “justif[ies] the infringement claimed.” The problem with all of these tests was that they were openly normative and subjective. By the mid-1960s, such tests would have been increasingly embarrassing for judges to use in an era when free-range judicial discretion was falling into disrepute. “Total concept and feel,” on the other hand, ostensibly assessed qualities of the works themselves, ones that exist independently of the observer—some sort of holistic aura of copyrightable expression that can be measured and assessed objectively. In actual application, of course, “total concept and feel” was no more limiting on judicial discretion than “aesthetic appeal” or “wrongful appropriation.” It was a sheep in wolf’s clothing.

Under cover of that disguise, judges were free to perform the sort of analysis Judge Yankwich had done at the trial court level in Bradbury. But rather than openly weed out uncopyrightable similarities and measure what remained, as Yankwich had done, courts would instead describe the two works in detail, and then at the end simply express the conclusion that the “total concept and feel” of the two works was different. The quote from Roth could thus be used as part of a sub silentio filtering of uncopyrightable material that the Roth court itself never performed. This allowed judges to continue making the sort of similarity decisions they had made in equity—decisions that were intertwined with intuition about protectability and substantiality—while avoiding the charge of lawless subjectivity.

Take Eden Toys v. Marshall Field & Co. (2d Cir. 1982), an early example of this procedure. Eden Toys sued Marshall Field’s for selling a similar snowman plush toy after negotiations to carry Eden’s fell through. Judge Edward Lumbard, who had been on the Fab-Lu panel, grumbled in dissent that the two snowmen had numerous similar features that would catch the attention of an ordinary observer: “They share similar composition (two snowballs, two buttons, scarf, face and hat), they share similar facial expressions, and, in general, they share the same ‘aesthetic appeal.'” While he admitted that the idea of a snowman plush is not copyrightable, he argued that Eden’s commercial success indicated that it had hit on some creative way to put the elements of a snowman together, even if that creativity was impossible to identify: “Eden Toys’ design and artwork earned the public’s favor. It is that design and that artwork that the copyright laws are intended to protect. It is that design and artwork — with its attendant commercial success — that Marshall Field has taken.”

Judges Ellsworth Van Graafeiland and Walter Mansfield, two more recent appointments, disagreed: “While the two snowmen are roughly the same size, their ‘total concept and feel’ are substantially different.” The majority opinion identified numerous similarities, the same that Lumbard had pointed to: two snowballs, black button eyes, black button noses, V-shaped mouths, two red buttons, scarves, and hats. But for each similarity, the majority found the particular way it was implemented to be different:

Each snowman has two red buttons. However, plaintiff’s are approximately 1-3/4″ to 2″ in diameter and are made of a soft clipped yarn. Defendant’s are approximately 1″ in diameter and have a texture more like felt. The top edge of the upper button on plaintiff’s toy is about 1/2″ below the green scarf that encircles its neck. The top edge of the upper button on defendant’s is about 1-1/2″ below the black and white scarf that it wears. There is a 1-1/4″ space between buttons on plaintiff’s snowman and a 1-3/4″ to 2″ space on defendant’s.

Snowman II has a floppy black hat set back off its forehead and a kelly green scarf with white fringes. Defendant’s toy has a shaped black hat with a red band that is shading its eyes and a black and white striped scarf with red fringes. The two snowmen are made of noticeably different material, that of plaintiff’s being softer and fluffier.

This is a far different exercise than simply finding the defendant’s work to be holistically dissimilar from the plaintiff’s. By drilling down into the details of execution, the Eden majority appears to have doing all three steps of the infringement analysis at once, without saying so: assessing the total number of similarities, excluding many of the most obvious ones as unprotectable, and determining that the remaining expression was more different that similar. The end result of that analysis was expressed as a conclusion that the two works lacked the same “total concept and feel.”

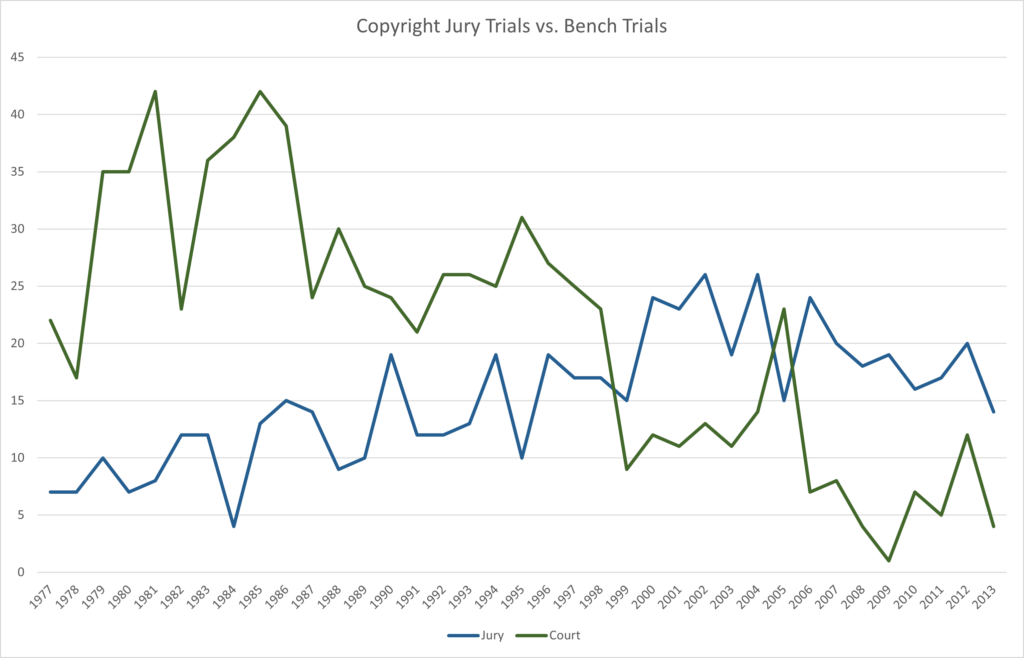

Numerous cases throughout the 1980s deployed this maneuver, often on summary judgment or even on appeal, resulting in judges, and not juries, making most substantial similarity determinations. First of all, for reasons that are not well understood, juries were typically not requested in copyright cases in the 1980s, meaning that the majority of copyright trials were bench trials. Second, even in cases where a jury was requested, the matter was often resolved on summary judgement. Technically, summary judgements in copyright cases were supposed to be granted for defendants only where either all of the claimed similarities between the two works consisted of uncopyrightable material, or “because no reasonable jury, properly instructed, could find that the two works are substantially similar.” But judges often took a fairly broad view of both what could be excluded as mere idea, and what a reasonable juror would find dissimilar. Third, the issue of substantial similarity was sometimes even resolved on appeal. The Second Circuit adopted a rule in the 1970s that appellate courts review substantial similarity decisions de novo, at least in bench trials where the works were in the record. In Concord Fabrics, Inc. v. Marcus Bros. Textile Corp. (2d Cir. 1969), the Second Circuit observed: “As we have before us the same record, and as no part of the decision below turned on credibility, we are in as good a position to determine the question as is the district court.” In many of these cases, as in Eden Toys, the court found the “total concept and feel” of the two works importantly different, and thus found for the defendant.

“Total concept and feel” thus served as a sort of meaningless incantation that directed attention elsewhere while judges made subjective determinations that were difficult or impossible to explain. Stanley Fish memorably compared such phrases to the anodyne advice once given by a major-league coach to his pitcher before taking the mound: “Throw strikes and keep ’em off the bases.” Between experts, who cannot possibly describe all of the particulars of a practical art, such instructions essentially boil down to, “Do all of the things that we both know you need to do.” And indeed, the Second Circuit later insisted that this was exactly the role that “total concept and feel” was supposed to play in infringement decisions. In Tufenkian Import/Export Ventures, Inc. v. Einstein Moomjy, Inc., Judge Guido Calabresi reviewed the history of “total concept and feel” in the Second Circuit, and concluded that the phrase was a form of “shorthand” that was not to be taken literally. Rather, in actual application, courts using the phrase “generally have taken care to identify precisely the particular aesthetic decisions — original to the plaintiff and copied by the defendant — that might be thought to make the designs similar in the aggregate.” In other words, “total concept and feel” served as “a reminder” to judges to wrangle all three of the squirrely aspects of an infringement decision: how much of the plaintiff’s work was taken, how much of the copied portions constituted expression, and whether the amount of expression taken was excessive. It was a way of saying to fellow judges, “throw strikes and keep ’em off the bases.”

Whatever the virtues of this method of analysis, it has at least three drawbacks in the modern procedural world. First, on its own terms, “total concept and feel” completely flunks as a legal test given our modern norms of “reasoned elaboration.” The barrage of criticism directed at the standard confirms this. Second, courts could only exercise their “unarticulated perception[s] of similarity” by being hypocritical about the standard for summary judgement. If substantial similarity is really just a question of fact, as courts since Arnstein have stated, then where there was any room for disagreement it technically had to go to the jury.

That leads to a third problem. Whatever secret meaning it might hold for judges, “total concept and feel” is not at all translatable for juries. To stick with Fish’s analogy, “throw strikes and keep ’em off the bases” only works as advice, if it works at all, between experts. As an instruction to a position player, or even worse, a spectator drafted from the stands, the advice is worse than useless: even assuming such a person could place pitches where they wanted them, not every pitch should be in the strike zone. So it is with “total concept and feel.” As a “reminder” to judges familiar with copyright law and the type of works in question, it may work as a form of “shorthand,” as Judge Calabresi called it. But taken at face value, asking juries to evaluate a work’s “total concept and feel” is asking for trouble.