What the Supreme Court Election tells us about Wisconsin’s Legislative Districts

You might think that adding up the results of a statewide April election in legislative districts should be simple, but it’s not.

First problem: the state currently doesn’t include political district numbers in the results for nonpartisan elections.

Second problem: votes in Wisconsin are counted, not in wards, but in combinations of wards called “reporting units,” and April nonpartisan elections can use different reporting units than in November elections.

Third problem: the reporting units used in April sometimes straddle partisan district lines.

So, my media consumer advisory is this; if you read an article telling you the results of an April election apportioned into legislative districts, you should expect to see an explanation of how the author obtained that data.

Here is how I do it. First, I identify the individual wards comprising each reporting unit. Then, I match those wards to the most recent GIS ward file I can find.[1] Every ward falls within a single political district, so I check to be sure that each ward in every reporting unit is assigned to the same district. If a reporting unit is split across multiple districts, I divide its vote according to the proportion of the reporting unit’s registered voters residing within each district.[2]

Here are the results of the 2025 April Supreme Court election between the Republican-endorsed candidate Brad Schimel and the Democratic-endorsed candidate Susan Crawford.

Crawford won 55.0% of the vote. Under the maps as currently used, this worked out to 54.5% of Assembly districts (54/99), 57.6% of Senate districts (19/33), and 50% of Congressional districts (4/8).

Table 1: Results of the 2025 Wisconsin Supreme Court Election in legislative districts

| seats won by | ||

| Schimel | Crawford | |

| State Assembly | 45 | 54 |

| State Senate | 14 | 19 |

| Congress | 4 | 4 |

The next table compares those results with some of the other recent redistricting plans, either proposed or used. Under the GOP-drawn maps used in the 2022 election, Crawford’s 10-point net victory would’ve resulted in 5-seat Republican majority in the Assembly and a 3-seat Republican majority in the Senate.

Table 2: Results of the 2025 Wisconsin Supreme Court Election in select alternative legislative districts

| State Assembly | State Senate | Congress | ||||

| Schimel | Crawford | Schimel | Crawford | Schimel | Crawford | |

| Evers’ 2024 (used in state legislature) | 45 | 54 | 14 | 19 | — | — |

| Evers’ Least Change | 47 | 52 | 17 | 16 | 4 | 4 |

| Districts used 2012-2020 | 48 | 51 | 17 | 16 | 5 | 3 |

| Districts used in 2022 | 52 | 47 | 18 | 15 | — | — |

| GOP Congressmen proposal 2021 | — | — | — | — | 5 | 3 |

Implications for 2026

Wisconsin’s state legislative maps now closely reflect the results at the top of the ticket. Both Donald Trump and Tammy Baldwin translated their narrow 1-point victories into 1-seat majorities of assembly districts. But actual Republican assembly candidates won a 5-seat majority.

In previous analyses, I found that incumbency advantage was worth about 4 points (net) for Republican Assembly candidates in both 2024 and 2022. This advantage means that the Republican Assembly majority can likely withstand election years resulting in a narrow statewide victory for Democrats. But anything approaching Crawford’s landslide victory puts many Republican incumbents in competitive districts much more at risk.

Here are the 6 closest battleground seats in the State Assembly. They are all seats which split their vote between the Assembly and presidential races. Five of them voted for Harris and a Republican legislator, while one voted for Trump and a Democratic legislator. In all instances, Susan Crawford defeated Schimel by double-digits.

Table 3: Election Results in Key Battleground Districts of the Wisconsin State Assembly

| Dem or Lib % minus Rep or Con % | ||||

| State Assembly | President | US Senate | WI Sup. Ct. | |

| 21st | -2.8 | 4.0 | 7.0 | 19.3 |

| 51st | -3.4 | 3.5 | 7.8 | 19.9 |

| 53rd | -1.2 | 4.4 | 6.1 | 18.0 |

| 61st | -3.2 | 2.2 | 3.7 | 13.5 |

| 88th | -0.7 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 11.3 |

| 94th | 0.6 | -2.1 | 0.0 | 12.3 |

Likewise, there are 4 battleground State Senate districts, one of which (the 31st) is currently represented by a Democrat and the rest by Republicans. Because Wisconsin elects odd-numbered senate districts during midterm years, these seats will hold their first elections under the new boundaries in 2026. As in the Assembly battlegrounds, Crawford won each of these districts by more than her statewide margin of victory.

Table 4: Election Results in Key Battleground Districts of the Wisconsin State Senate

| Dem or Lib % minus Rep or Con % | |||

| President | US Senate | WI Sup. Ct. | |

| 5th | 5.9 | 5.0 | 13.5 |

| 17th | 1.0 | 4.6 | 17.9 |

| 21st | 1.2 | 2.2 | 10.7 |

| 31st | 2.2 | 4.7 | 18.0 |

[1] I begin with the most recent LTSB stateward ward boundary file (Jan. 2025 in this case). When recent annexations or incorporations make these boundaries already out-of-date, I obtain updated boundaries from the county. For the April 2025 election, I needed updated ward boundary files from Dane and Waukesha counties.

[2] I do this using a geocoded copy of the state’s voter file, but it could also be done using the state’s monthly ward-level registered voter report.

The Fall 2024 Marquette Lawyer magazine included essays looking at the broad question of why so much K–12 education reform brings so little progress. If I do say so myself (and I was much involved), it was a provocative and thoughtful discussion.

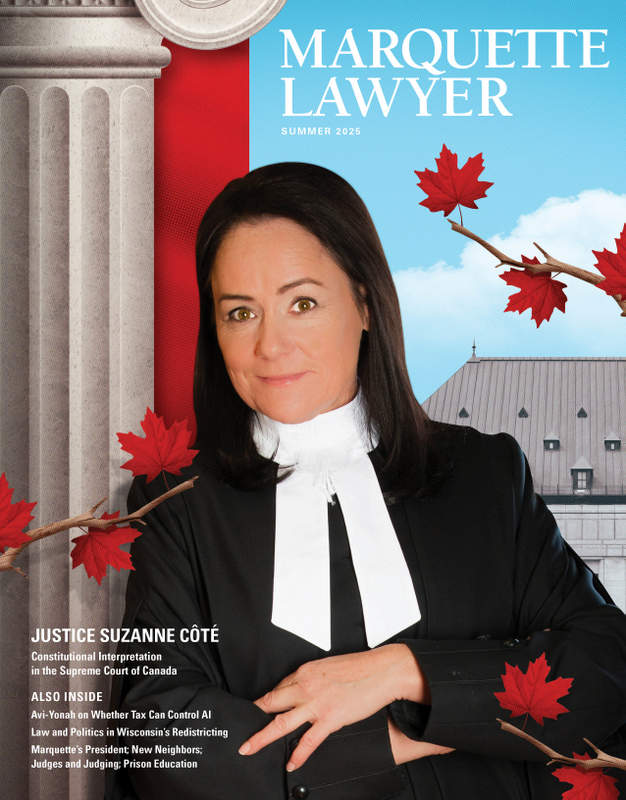

The Fall 2024 Marquette Lawyer magazine included essays looking at the broad question of why so much K–12 education reform brings so little progress. If I do say so myself (and I was much involved), it was a provocative and thoughtful discussion. Marquette Lawyer is not a news magazine, strictly speaking. In fact, there is hardly anything left of news magazines in the United States. But that hardly means there isn’t a lot to learn about what is in the news. And the Summer 2025 issue of Marquette Lawyer certainly provides news in the sense of insights on several major current matters.

Marquette Lawyer is not a news magazine, strictly speaking. In fact, there is hardly anything left of news magazines in the United States. But that hardly means there isn’t a lot to learn about what is in the news. And the Summer 2025 issue of Marquette Lawyer certainly provides news in the sense of insights on several major current matters.