Eleven Thoughts on Making the Work of K–12 Teachers More Successful

The Fall 2024 Marquette Lawyer magazine included essays looking at the broad question of why so much K–12 education reform brings so little progress. If I do say so myself (and I was much involved), it was a provocative and thoughtful discussion.

The Fall 2024 Marquette Lawyer magazine included essays looking at the broad question of why so much K–12 education reform brings so little progress. If I do say so myself (and I was much involved), it was a provocative and thoughtful discussion.

In the end, one sentence stood out to me and others involved in planning programs at Marquette Law School’s Lubar Center for Public Policy Research and Civic Education. Robert Pondiscio, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, wrote, “What if, instead of pulling policy levers, we redirected the reform movement’s energy and enthusiasm toward improving classroom practice?”

Well, what if? Pondiscio argued that better training of teachers and steps to lighten the workload of teachers would open paths to better results. He said too much is being expected of many teachers now. He advocated particularly for providing teachers in many subjects high-quality curricular materials so they don’t have to spend large amount of time developing lessons plans and can focus on actual teaching and connecting with students.

To advance the conversation, Marquette Law School, teaming with the Marquette College of Education, hosted an in-person forum on May 8, 2025, titled “Focusing K–12 Education Reform on Teaching Efforts.” Before an audience in the Lubar Center of more than 100, including a number of leaders in Wisconsin education, Pondiscio expanded on his thinking; Sarah Almy, chief of external affairs for the National Council on Teacher Quality, offered additional perspective; and a panel of Wisconsin educators offered their thoughts.

We intend to pursue this important conversation in further events and in the Marquette Lawyer magazine. For the moment, let me offer a set of thoughts from the conference’s speakers.

Pondiscio on the teaching workforce overall: With about 3.7 million K–12 teachers nationwide, it is unrealistic to expect the large majority to be “saints and superstars.” The large majority, he said, are people who want to be good teachers but are, for one reason or another, more middle-of-the-pack in their work. But, he said, they could become more successful. “That’s why I come back to raising not the level of teacher quality, but of quality teaching—making this job doable by the teachers we have and not by the teachers we wish we had.”

Pondiscio on reducing the burden on teachers who often must deal with duties that go beyond actual teaching: “Something’s got to come off the teacher’s plate. And the most obvious thing to me is curriculum. . . . Somebody else can write the curriculum. Nobody else can give feedback, get to know the kids, etc. So that one basic shift alone would probably make a difference.”

Pondiscio, when asked who will do all the non-teaching things teachers do now: “I don’t know what the answer is, but I know what the answer is not. It’s not asking Miss Jones to do it. . . . This is about making teaching easier and doable.”

Pondiscio on the education reform movement in recent years: Some reformers wanted to “beat teachers up—you know, ‘look at these terrible teachers, they’re lazy.’ A lot of us in education reform said, ‘just fire bad teachers and all will be well.’” In fact, he said, teachers were not “the sinners,” but “the sinned against,” by being put in positions where they faced unreasonable demands and were not trained well. “The teachers are not the bad guys here. When teachers know what to do, they’re not that bad.”

Almy on the gap between policy and practice in education: “I think a lot of times we really fall down on translating policy into implementation and practice. . . . I think we put a lot of energy, whether it’s at the state level or the district level, into getting the policy passed and the political pieces of that. And then everyone takes a sigh of relief and sort of assumes a lot of this will translate at the classroom level.” But pushing waves of reform onto teachers and local school leaders often means that things don’t change “because the classroom door closes and the teacher does whatever the teacher’s going to do.”

Almy on teacher-training programs, a major focus of her organization: “We need to stop putting all of the onus on training teachers on the districts, and we need to ensure that we’re holding our teacher-prep programs to really high expectations.”

Taylor Thompson, a first-year first-grade teacher from Oshkosh who has used a literacy curriculum called Core Knowledge Language Arts: “CKLA has actually given me a clear, structured path that supports my teaching and my students’ learning . . . . That structure has allowed me to focus on how we are teaching things, rather than spending hours worrying and figuring out what we are teaching.”

Maggy Olson, director of equity and instruction for the Greendale School District in suburban Milwaukee, on those who say education is not succeeding: “I think so often in education that is the narrative: ‘It’s impossible.’ It is, ‘teachers are failing, kids are failing, our schools are failing, it’s a mess.’ I want to say that is absolutely false. . . . Our schools are not failing. They’re doing more than they’ve ever done before.”

Kanika Burks, chief schools officer for Howard Fuller Collegiate Academy, a Milwaukee charter school, on the obligation of administrators to support teachers: Administrators need to “pay attention to the heart of the people that are in front of you. . . . If the person who is in front of our young people is not healthy, if their heart is breaking, if they are breaking down, they are not going to be the most effective person regardless of the curriculum and the faith in them.”

Cynthia Ellwood, a Marquette University College of Education faculty member, on striking a balance between curriculum and teacher presentation: “It’s not just a matter of going out there and finding the perfect material. I don’t think it boils down to a single approach to curriculum [or other factors]. . . . We must know that every single one of our students is capable of high intellectual thought, that they are capable of seeing themselves as intellectuals. And what we’re doing right now is not building pathways so that every child is offered this incredible challenging curriculum and the appropriate supports that make it possible for them to succeed.”

Olson on the future: “Is there hope? Yes, there is so much hope in our children and our educators. Right now, we are in a very dark place. I would argue that we are not in a tomb, we are in a womb, and we’re ready to be reborn. . . . . Hope is in the work that we have moving forward.”

The in-print symposium in the fall 2024 Marquette Lawyer magazine may be read by clicking here (online version) or here (PDF).

Video of the May 8 program at Eckstein Hall may be viewed by clicking here.

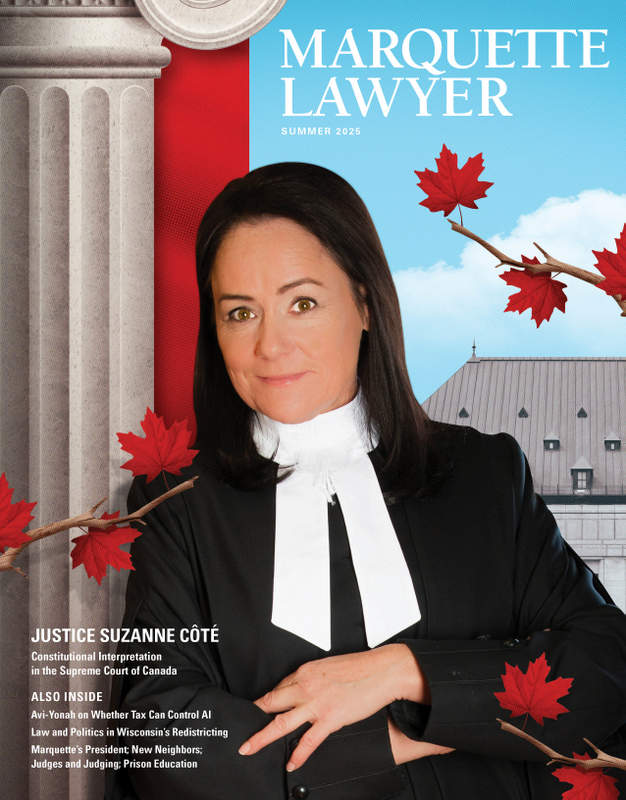

Marquette Lawyer is not a news magazine, strictly speaking. In fact, there is hardly anything left of news magazines in the United States. But that hardly means there isn’t a lot to learn about what is in the news. And the Summer 2025 issue of Marquette Lawyer certainly provides news in the sense of insights on several major current matters.

Marquette Lawyer is not a news magazine, strictly speaking. In fact, there is hardly anything left of news magazines in the United States. But that hardly means there isn’t a lot to learn about what is in the news. And the Summer 2025 issue of Marquette Lawyer certainly provides news in the sense of insights on several major current matters. A problem, before a solution: The problem is that a large number of registered voters in Wisconsin do not know enough about or do not have an opinion of the two candidates running in the April 1 election for a seat on Wisconsin’s Supreme Court. Results of the Marquette Law School Poll released on March 5 found that 38 percent of voters do not have an opinion about Brad Schimel, former Wisconsin attorney general and now a Waukesha County circuit judge, and 58 percent do not have an opinion about Susan Crawford, a Dane County circuit judge. The two are squaring off in what some commentators have called the most important election underway currently in the United States.

A problem, before a solution: The problem is that a large number of registered voters in Wisconsin do not know enough about or do not have an opinion of the two candidates running in the April 1 election for a seat on Wisconsin’s Supreme Court. Results of the Marquette Law School Poll released on March 5 found that 38 percent of voters do not have an opinion about Brad Schimel, former Wisconsin attorney general and now a Waukesha County circuit judge, and 58 percent do not have an opinion about Susan Crawford, a Dane County circuit judge. The two are squaring off in what some commentators have called the most important election underway currently in the United States.