Tesla Wins First Trial Involving “Autopilot,” but More Serious Cases Loom

On April 21, Tesla was handed a victory in the first-ever trial involving Autopilot. The case provides an early glimpse into how efforts to hold Tesla liable for Autopilot crashes might fare with juries, and the press has called the trial a “bellwether” for others that are currently pending. Nevertheless, a close look at the facts indicates that plaintiffs might have more success in the future.

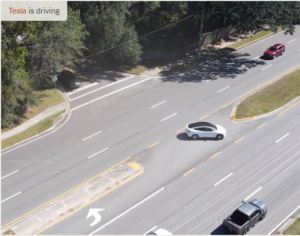

The plaintiff, Justine Hsu, was driving her Tesla in stop and go traffic on a surface street with a concrete median in Arcadia, California. She activated Autopilot, a suite of features that includes “traffic aware cruise control,” a system that automatically adjusts speed based on traffic conditions and that is, according to her complaint, popular among Tesla owners in heavy traffic. The car was driving about 20-30 miles per hour when it suddenly swerved off the road and into the median. At this point the car’s airbag deployed, shattering Hsu’s jaw and knocking out several of her teeth. (The airbag manufacturer was also a defendant in the case, and was also found not liable by the jury).

In a few ways, Hsu’s case represents a classic fact pattern involving Autopilot. On one hand, the system clearly did not function as it was designed to do. Autonomous vehicles should not suddenly swerve off the road, and yet in several cases Autopilot has done just that. One such case was the crash that killed Walter Huang, who was using Autopilot on his commute to work when his car veered off the highway and into a concrete barrier at more than 70 miles per hour. On a basic level, Hsu’s case was an effort to hold Tesla liable for this malfunction, and also for the misleading way Autopilot is marketed.

On the other hand, Hsu was using Autopilot in a setting where it was not supposed to be used.

This week the New York Times

This week the New York Times