The Surprisingly Confused History of Fair Use: Is It a Limit or a Defense or Both?

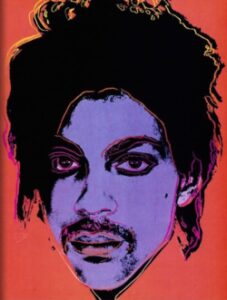

The Supreme Court’s upcoming oral argument in Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith will focus on one of the most practically significant of the thorny questions of copyright law: what uses are fair? Fair use is both crucially important and profoundly murky. Indeed, its murkiness is part of its design. The doctrine of fair use has served since its inception as a sort of an amorphous safe haven for unwritten but important limits on a statutory right, decided on a case-by-case basis. It’s the Mutara Nebula of copyright law.

The Supreme Court’s upcoming oral argument in Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith will focus on one of the most practically significant of the thorny questions of copyright law: what uses are fair? Fair use is both crucially important and profoundly murky. Indeed, its murkiness is part of its design. The doctrine of fair use has served since its inception as a sort of an amorphous safe haven for unwritten but important limits on a statutory right, decided on a case-by-case basis. It’s the Mutara Nebula of copyright law.

That makes fair use a bit of an anachronism in a modern age where statutes are read literally and every degree of judicial freedom has been crushed down into a multi-part test. Indeed, fair use’s role in copyright law has arguably grown as judges, shut out of other ways of using discretion to decide copyright claims, have turned to fair use to accomplish what substantial similarity or limitations on scope once did.

That growing importance has set up the current conflict. In the last several decades, there have been attempts to define fair use more rigorously, to make it more predictable and ensure consistent application. The AWF case involves one of those — defining fair use as revolving around a single, critical concept: “transformativeness.” I’ll take a look at those efforts in a future post.

But there’s another aspect of the AWF case that makes it difficult. Fair use has historically served not one but two murky and undefined roles.

Next week, the Supreme Court will hear oral argument in

Next week, the Supreme Court will hear oral argument in  Our Student Contributor for October is 3L Emilie Smith. Emilie is from Green Bay, Wisconsin, and has a strong interest in Business Law and Intellectual Property Law. She currently has a comment pending publication in the Marquette Law Review on the digital recreation of copyrighted tattoos for use on video game avatars. Welcome Emilie!

Our Student Contributor for October is 3L Emilie Smith. Emilie is from Green Bay, Wisconsin, and has a strong interest in Business Law and Intellectual Property Law. She currently has a comment pending publication in the Marquette Law Review on the digital recreation of copyrighted tattoos for use on video game avatars. Welcome Emilie!