Jury Duty in de Tocqueville’s Time and in the Present

Alexis de Tocqueville was a French aristocrat sent by his country to inspect American penitentiaries during the 1830s. He dutifully delivered his report, but he also found himself interested in more than penitentiaries. In Democracy in America (1835), he provided a wide-ranging and to this day highly regarded account of life in the youthful, rambunctious American Republic. Somewhat surprisingly, de Tocqueville discussed at length the role and function of jury duty.

Although de Tocqueville recognized the jury as a “juridical institution,” that is, a body that renders verdicts, he was more interested in the jury as a “political institution.” He argued that the jury “puts the real control of affairs into the hands of the ruled, or some of them, rather than into those of the rulers.” The jury was a vehicle through which the citizenry could exercise its sovereignty.

What’s more, jury duty struck de Tocqueville as a “free school.” “Juries, especially civil juries,” he thought, “instill some of the habits of the judicial mind into every citizen, and just those habits are the very best way of preparing people to be free.” As a form of “popular education,” jury duty offers practical lessons in the law and teaches jurors their rights under the law.

Overall, de Tocqueville was pleased Americans took eagerly to jury duty and felt robust, active juries were extremely important in the success of the nation. Jury duty, he said, “makes men pay attention to things other than their own affairs” and thereby “combat that individual selfishness which is like rust in society.”

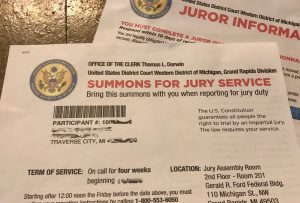

How disappointed de Tocqueville would be learn how people perceive jury duty in the present. While people who actually serve on juries tend to say their experiences were positive ones, a huge percentage of Americans dread receiving a summons for jury duty and do their best to avoid serving. Websites such as “How to Get Out of Jury Duty” and “10 Ways to Avoid Jury Duty” are popular.

Numerous social commentators have noted how the pandemic has hit the least powerful and prosperous parts of the population the hardest. Infections, hospitalizations, and deaths have been disproportionally high among the poor, people of color, recent immigrants, Native Americans, and the elderly.

Numerous social commentators have noted how the pandemic has hit the least powerful and prosperous parts of the population the hardest. Infections, hospitalizations, and deaths have been disproportionally high among the poor, people of color, recent immigrants, Native Americans, and the elderly. I welcomed the

I welcomed the