Major League Baseball is changing again. For more than nine decades, from 1901 to 1994, it was a cardinal rule of baseball that teams in the American and National League met in exhibition games, the All-Star Game, and the World Series, but never in games that counted during the regular season. Since 1994, we have had annual interleague play, but it has always been constricted to two discreet periods in the early and mid-summer.

Major League Baseball is changing again. For more than nine decades, from 1901 to 1994, it was a cardinal rule of baseball that teams in the American and National League met in exhibition games, the All-Star Game, and the World Series, but never in games that counted during the regular season. Since 1994, we have had annual interleague play, but it has always been constricted to two discreet periods in the early and mid-summer.

Now, it has been announced that in 2013 the Houston Astros will move to the American League, and Major League Baseball will realign into two 15-team leagues, each composed of three divisions of five teams each. For the first time in the 136-year history of Organized Baseball, there will be an odd number of teams in both major leagues, necessitating interleague play throughout the season.

This, it turns out, is not the first time that major league owners have discussed such an arrangement.

In November, 1960, having announced the transfer of the “old” Washington Senators to Minneapolis-St. Paul and the award of a new expansion franchise for the Nation’s capital (the “new” Washington Senators), American League president Joe Cronin suggested that the National League immediately add one team in either New York or Houston, and that the two leagues play an interlocking 166 game schedule in 1961.

The circumstances leading up to this proposal were an outgrowth of the rather hasty decision made by the two Major Leagues in the late summer of 1960 to increase the number of teams in the National and American Leagues for the first time since 1900.

The decision to expand was prompted by the threat posed by a planned “third” major league, the Continental League. The Continental League, headed by legendary baseball executive Branch Rickey, had planned to begin play in 1961, but it was dissuaded from entering the field by the promise of the two existing leagues to add four more teams in the near future and another four by the end of the decade of the 1960’s.

The National League was the first to announce its plans to expand, reporting on October 17, 1960, only four days after the most famous World Series game in history, the Pittsburgh Pirates dramatic, bottom of the 9th 10-9 victory over the New York Yankees, that it would add teams in New York City and Houston for the 1962 season.

The above-mentioned “nine team league” proposal turns out to have been a product of the ineptness of the American League’s belated effort to match the expansion plans of the National League. On October 27, ten days after the National League’s expansion announcement, the American League hastily announced that it was adding teams in Minneapolis and Los Angeles, which would begin play in 1961. (The current Senators, as mentioned above, would move to the Twin Cities and a new team would be based in Washington.)

The decision to place a team in the Twin Cities was not controversial at all, but there were a number of problems with the second new team going to Los Angeles. Some owners believed that the “agreement” that had led to the disbandment of the Continental League had included a promise to award expansion franchises to teams from the Continental League, or at least to its cities. (The National League had done this, admitting to membership the ownership groups of the New York and Houston teams from the CL.) Minneapolis was a Continental League city, but the new team went not to the CL owners but to the current owners of the AL’s Washington Senators. Los Angeles, in contrast, had not even been a Continental League city. (The five remaining CL cities were Dallas-Ft. Worth, Atlanta, Toronto, Buffalo, and Denver.)

Moreover, under the Major League agreement entered into by the National and American Leagues, no major league team could be moved into the territory of an existing team without the unanimous agreement of all the owners in both leagues, a rule that in effect gave existing owners an absolute veto over the relocation of any team to their territory.

This meant that the American League could place an expansion team into Los Angeles without gaining the consent of Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley. While the Yankees had agreed not to object to the placement of a new National League team in New York as part of the settlement with the Continental League, the issue of moving a new team to Los Angeles had never been on the table.

Almost immediately, plans for the new Los Angeles team started to go awry, as O’Malley made it quite clear that he was not at all enthusiastic at the idea of a second Major League team in Los Angeles. An ownership group led by Hall-of-Fame outfielder Hank Greenberg was the early front-runner to receive the new Los Angeles franchise, but on November 17, the same day that the new Washington team was awarded to World War II hero Elwood Quesada, the Greenburg group dropped out of the running.

Although Chicago insurance man Charlie Finley immediately placed a bid for the new Los Angeles team, the AL owners began to have second thoughts about the wisdom of going into LA in 1961. Five days later, on November 22, league president Joe Cronin announced a new AL proposal for two 9-team leagues featuring interleague play. As part of the proposal, it would delay the creation of its Los Angeles team until 1962, so there would be only a single team in the City of Angels in 1961. Cronin asked that the National League respond by December 5 (the date of the next National League owners’ meeting).

Although it was not initially announced as part of the proposal, it was subsequently reported that the expectation was that the 9th team in the National League would be Houston, and that the establishment of the second New York team would be held off until 1962 (as originally scheduled). If implemented in this manner, the plan would leave both Los Angeles and New York as single-team cities in 1961.

There were also conflicting reports as to who had come up with the 9-team plan. In some accounts, it was New York Yankees owner Dan Topping, while in others the idea was said to have originated with Los Angeles Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley. Both men would obviously have benefitted from the delayed entry of a new team into their market, plus O’Malley in particular did not want new competition until the completion of his new stadium at Chavez Ravine, which was scheduled to open in 1962.

Although baseball fans are often thought to be instinctively conservative, the initial public reaction to the 9-team league with interleague play proposal was generally favorable. A front page story in the November 30, 1960, Sporting News (the so-called Bible of baseball which was published a week before its cover date) described the receptive response in a story with the headline, “Fans Want Something New, Get It in 9-Club Majors, Inter-Loop Play.”

However, National League opposition to the 9-team plan surfaced almost immediately. By 1960, it was clear that the National League was the more popular league of the two, and many NL owners saw nothing to be gained by having to share the home gate with teams from the other league. Moreover, neither the Houston nor the New York owners were very enthusiastic about the idea of fielding a team by April of 1961.

By November 24, the New York Times and a raft of United States and Canadian newspapers were reporting that both the 9-team league plan and the idea of an American League team in Los Angeles seemed doomed and that the new tenth team in the American League would be Toronto, where the existing AAA team was supposedly to be elevated to major league status. In describing Cronin’s plan only two days after it was announced, a Milwaukee Journal headline somewhat prosaically observed, “Latest Plan Headed for the Scrap Heap.” Commissioner Ford Frick also announced that adoption of the plan seemed unlikely, but he nevertheless scheduled a special meeting for Wednesday, December 2, to discuss the possibility.

By November 26, Toronto owner Jack Kent Cooke had backed out of his interest in an expansion team, and there were rumors that the American League was about to announce that its expansion plans would be delayed until 1962. What was less visible was a debate going on among American league team owners. In an era when the two major leagues had much greater autonomy than they do today, one group of AL owners sought to work out an accommodation with O’Malley over Los Angeles while the other group advocated placing a team in Los Angeles whether or not National League approval was forthcoming.

There were also numerous calls from throughout the baseball world for Commissioner Ford Frick to use his powers to repeal the rule that effectively gave individual owners a veto power over the location of expansion teams.

As expected, on December 5, the National League rejected the proposal for two 9-team leagues playing an interlocking schedule. The official reason given was the inability of the Houston team to be ready for the 1961 season. However, to the surprise of many, Walter O’Malley and his fellow National League owners also announced that they were dropping their objection to the creation of a second Los Angeles team and that the American League was welcome to expand into the city for the 1961 season.

The following day, the American League announced that a new Los Angeles franchise, to be called the Angels, had been awarded to an ownership group headed by Gene Autry, the noted cowboy actor and singer who had become an entertainment mogul in the 1950’s.

The American League had established itself in the nation’s third largest city, but the story quickly surfaced that O’Malley’s permission did not come without a price. To get the Dodgers to drop their objections, Autry, who was already on friendly terms with O’Malley, agreed to pay a $350,000 indemnity to the Dodgers; agreed to telecast no more than 11 of his team’s 81 road games during the 1961 season; agreed to play the team’s 1961 home games in Los Angeles’ tiny Wrigley Field rather than the spacious LA Coliseum; and agreed to become the tenants of the Dodgers for at least three years once the Dodger-owned ballpark opened in 1962.

The 1961 season, which featured the famous assault on Babe Ruth’s single season home run record by Roget Maris and Mickey Mantle, was played with ten teams in the American League and eight in the National. In 1962, the Mets and Colt .45s (later Astros) joined the National League as scheduled. Both leagues played as 10-team leagues until 1969 when both expanded to 12 teams.

Although the idea of an odd number of teams in each league would not resurface until 2012, the concept of interleague play continued to be a regular topic of discussion in baseball circles, as it had been throughout the 20th century. Although actual regular season interleague play did not begin until 1994, such proposals were a regular feature of baseball deliberations.

In fact, the American League had proposed a limited number of interleague games in 1959, only to have it voted down by the National League. Even after the expansion of 1961 and 1962, the issue continued to be debated, and in early 1963, a Sporting News poll of its readers reported that almost 70% liked the idea. Ordinarily, proposals for interleague play came from the league with the weaker attendance—before 1960, the National and after that the American—only to be rejected by the better drawing league.

Of course, the days of no interleague play are long gone, and beginning in 2013, interleague play will be a daily feature of Major League baseball.

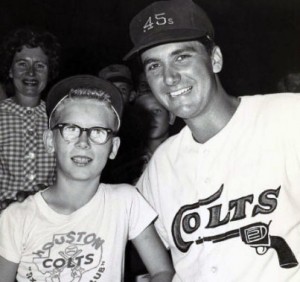

The 2012 season will mark the 50th anniversary of Houston’s National League team. (Somewhat ironically, this happens just before the team is shifted to the American League.) To commemorate this milestone, the Astros have scheduled a number of “throwback” games during the 2012 season. In honor of the team’s entry into major league baseball as an expansion team in 1962, players on the team will wear uniforms from that inaugural season.

The 2012 season will mark the 50th anniversary of Houston’s National League team. (Somewhat ironically, this happens just before the team is shifted to the American League.) To commemorate this milestone, the Astros have scheduled a number of “throwback” games during the 2012 season. In honor of the team’s entry into major league baseball as an expansion team in 1962, players on the team will wear uniforms from that inaugural season.