Time is Running Out to Confirm Judge Garland

The unprecedented, and unconstitutional, obstruction of Supreme Court nominee Judge Merrick Garland is just one of many recent missteps by Republican leaders. For example, mainstream Republican presidential candidates strategically withheld their attacks on Donald Trump during the primary season, in the hopes that he would be an easy target to topple once the field sorted out. This was a major blunder. More broadly, the decision of Republican leaders in Congress to make the repeal of the Affordable Care Act the centerpiece of their legislative agenda, at a time when Republicans lacked a veto-proof majority, was an empty gesture which merely fueled anger among their Party’s base and ultimately made Trump possible. Both of these decisions were political calculations that seemed clever at the time, but which turned out to have disastrous consequences for the Republican Party. However, the unjustified refusal to hold hearings on a highly-regarded and moderate Supreme Court nominee has the potential to dwarf every other political miscalculation that Republican leaders have made over the last eight years.

The unprecedented, and unconstitutional, obstruction of Supreme Court nominee Judge Merrick Garland is just one of many recent missteps by Republican leaders. For example, mainstream Republican presidential candidates strategically withheld their attacks on Donald Trump during the primary season, in the hopes that he would be an easy target to topple once the field sorted out. This was a major blunder. More broadly, the decision of Republican leaders in Congress to make the repeal of the Affordable Care Act the centerpiece of their legislative agenda, at a time when Republicans lacked a veto-proof majority, was an empty gesture which merely fueled anger among their Party’s base and ultimately made Trump possible. Both of these decisions were political calculations that seemed clever at the time, but which turned out to have disastrous consequences for the Republican Party. However, the unjustified refusal to hold hearings on a highly-regarded and moderate Supreme Court nominee has the potential to dwarf every other political miscalculation that Republican leaders have made over the last eight years.

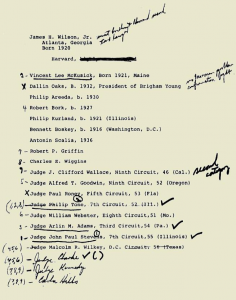

First of all, it is important to recognize that Judge Merrick Garland is a laudable nominee for the U.S. Supreme Court. He is a former federal prosecutor, a highly respected Judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, and someone identified by Senator Orrin Hatch and other prominent Republicans (prior to his nomination) as the type of judge who would receive bi-partisan support in Congress. Post-nomination arguments raised about Judge Garland’s supposed lack of respect for the Second Amendment are not justified by his actual opinions and, in reality, are merely a fig leaf contrived to rationalize opposition to the nomination by Republican lawmakers.

In addition, the refusal of the Senate to take up the nomination is a clear violation of the Constitution.