Innovation at the Food-Energy-Water Nexus

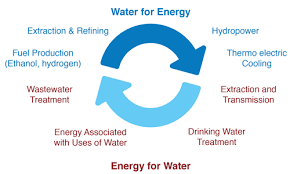

I have previously written in this space about the importance of policy innovation at the food-energy-water nexus. On Tuesday, May 16, Marquette Law School will host an interactive and interdisciplinary workshop to explore those issues, drawing from engineering, legal, scientific, and policy spheres. The workshop format and accompanying discussions will (1) provoke conversations about overcoming barriers to the implementation of innovative water solutions, (2)  stimulate ideas for focused academic research in the nexus, and (3) drive the development of organizational policy and technology roadmaps. The event incorporates sessions on energy use, recovery, and minimization at water and wastewater utilities; on groundwater; on agricultural sustainability and food waste; and on ethical considerations for stakeholders, a topic often absent from similar events. A working lunch and roundtable discussion as well as breakout sessions will invite and encourage broad-based attendee participation. Attendees will also have numerous opportunities to network with experts, researchers, and students. This event is sponsored by a grant from the National Science Foundation I/UCRC for Water Equipment and Policy. More details, including an agenda and registration information, are available here. Confirmed participants include:

stimulate ideas for focused academic research in the nexus, and (3) drive the development of organizational policy and technology roadmaps. The event incorporates sessions on energy use, recovery, and minimization at water and wastewater utilities; on groundwater; on agricultural sustainability and food waste; and on ethical considerations for stakeholders, a topic often absent from similar events. A working lunch and roundtable discussion as well as breakout sessions will invite and encourage broad-based attendee participation. Attendees will also have numerous opportunities to network with experts, researchers, and students. This event is sponsored by a grant from the National Science Foundation I/UCRC for Water Equipment and Policy. More details, including an agenda and registration information, are available here. Confirmed participants include: