Wisconsin and the Repeal of Prohibition

This past December 5 marked the 80th anniversary of the repeal of Prohibition, America’s experiment in the creation of an alcohol-free society.

This past December 5 marked the 80th anniversary of the repeal of Prohibition, America’s experiment in the creation of an alcohol-free society.

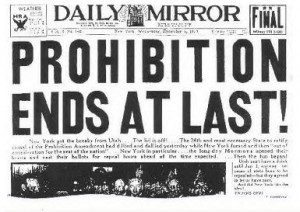

Prohibition officially ended in 1933 with the ratification of the 21st Amendment to the United States Constitution. The new Amendment repealed the earlier 18th Amendment, which had made the sale and consumption of alcoholic beverages illegal in the United States.

The repeal of Prohibition is an event that has been celebrated daily in Wisconsin for the past eight decades.

Somewhat remarkably, Wisconsin, long associated with the production of alcoholic spirits, did actually vote for Prohibition. On January 17, 1919, in the wake of intense anti-German sentiment throughout the United States and in the aftermath of World War I, in which the U.S. government had used its war powers to sharply curtail the production of alcoholic beverages, the Wisconsin legislature approved the 18th Amendment by a majority vote. However, in “defense” of the legislature, Wisconsin’s approval did not come until after the Prohibition Amendment had already been ratified by the requisite number of states to bring it into law.

At the time of the Wisconsin vote, 39 other states had already ratified the proposed Amendment, three more than necessary. North Carolina, Utah, Nebraska, Missouri, and Wyoming had all ratified the Amendment the previous day (January 16), bringing the number of ratifying states to 38. (The 39th state, Minnesota, ratified the Amendment earlier the same day that Wisconsin voted for it.) That the Amendment was already set to take effect was known in Wisconsin at the time of the vote.

But having approved of Prohibition in 1919, the enthusiasm of Wisconsin residents for the “Noble Experiment” quickly waned, even though 45% of the state had actually enacted local option prohibition laws prior to the passage of the 18th Amendment.

Even the state’s highest ranking officials began to express their reservations. Republican Governor John James Blaine (of Wingfield, Wisconsin) began to publically question the wisdom of Prohibition as early as 1923, and by the middle of the decade state (as opposed to federal) enforcement of the anti-alcohol laws had come to a halt.

In 1926, advocates of repeal managed to get a measure on that year’s state ballot asking voters if they thought the 18th Amendment should be repealed or drastically modified, and just under 72% of participants voted “yes.” The following year the legislature adopted a statute legalizing beer, which was vetoed by new governor Fred Zimmerman (R. Milwaukee), but only on the grounds that it was clearly unconstitutional.

In 1928, Wisconsin went so far as to repeal all of its state laws enforcing Prohibition, and by 1932, the party platforms of both Republicans and Democrats openly called for repeal of the 18th Amendment.

Wisconsin eventually took the lead of the repeal movement when, on December 6, 1932, former Governor Blaine, now a United States Senator, introduced the original draft of the 21st Amendment into Congress. (Blaine himself was a lame duck senator at the time, having been defeated in the Republican primary in 1932, while running for a second term.) Although Blaine is largely forgotten today, he was once widely known among drinking Americans as the “Father of the 21st Amendment.”

Unlike other Constitutional Amendments, the terms of the 21st Amendment required that it be ratified by state constitutional conventions, rather than by the state legislatures. After the amendment was approved by both houses of Congress by the requisite 2/3 majorities, the Wisconsin legislature quickly scheduled an election of delegates to a state convention.

Not surprisingly, every seat in the April convention was won by an advocate of repeal. On April 25, 1933, the delegates assembled and voted unanimously to support the 21st Amendment. By doing so, they made Wisconsin the second state to ratify the Amendment. Michigan had beaten Wisconsin to the punch, but only by a mere ten days.

Within a week, a bill legalizing alcoholic beverages had been introduced into the Wisconsin legislature in anticipation of the Amendment’s impending passage. As it turned out, there was more resistance to repeal than some had anticipated (especially in rural areas and in the South), and ratification did not occur for another 7 ½ months. However, the new Amendment officially took effect on December 5, 1933, when Utah became the 36th state to ratify.

According to contemporary accounts, large crowds took to the streets in Milwaukee that day to celebrate the return of alcoholic beverages and the revival of the Brew City’s beer and liquor industries.