Our March Guest Blogger is Here!

Please join me in welcoming our Guest Blogger for the month of March.

Please join me in welcoming our Guest Blogger for the month of March.

Our Alumni Blogger of the Month is Attorney Brandon Jubelirer. He is currently an associate at Hawks Quindel. His law practice primarily consists of litigating a wide variety of worker’s compensation matters on behalf of injured and wrongfully terminated workers. Before joining Hawks Quindel as an associate, Attorney Jubelirer served as a law clerk with the firm for over a year and a half. Throughout his legal education, Attorney Jubelirer also interned for a federal judge in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Wisconsin, served on the board of directors for the Marquette Labor & Employment Law Society, and performed pro-bono service for the Sojourner Family Peace Center’s Domestic Violence Clinic in connection with Marquette University Law School. Attorney Jubelirer graduated cum laude from Marquette University Law School. Prior to entering law school, Attorney Jubelirer earned his B.A., cum laude, from the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee with a double major in political science and history. He also graduated from the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee Honors College program.

We look forward to your posts.

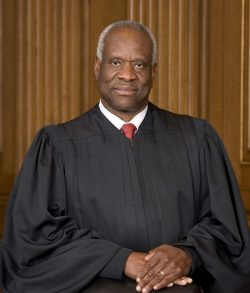

Last spring in Washington, D.C. at the Federalist Society’s National Student Symposium, Justice Thomas told a room full of law students to “get rid of [their] pessimism.” Justice Thomas, your words have been ringing in my ears. Admittedly, many aspects of America’s contemporary legal and political landscape engender a lingering pessimism in me. I’d like to step back a moment from this divisive arena we encounter every day and briefly discuss a few points of optimism.

Last spring in Washington, D.C. at the Federalist Society’s National Student Symposium, Justice Thomas told a room full of law students to “get rid of [their] pessimism.” Justice Thomas, your words have been ringing in my ears. Admittedly, many aspects of America’s contemporary legal and political landscape engender a lingering pessimism in me. I’d like to step back a moment from this divisive arena we encounter every day and briefly discuss a few points of optimism.