Whom Do I Want As My King?

Part Three of a series on Election Law, providing context to our system of government, our election process and a little history to evaluate and consider in the candidate-debate. Prior blog posts discussed the lead-up to the Constitutional Convention of 1787 and provided context to the debate over the American system of government. Here is further context. For a more in depth discussion and a great read — upon which much of this blog finds its genesis — look to Ray Raphael’s book Mr. President: How and Why the Founders Created a Chief Executive (2012).

Part Three of a series on Election Law, providing context to our system of government, our election process and a little history to evaluate and consider in the candidate-debate. Prior blog posts discussed the lead-up to the Constitutional Convention of 1787 and provided context to the debate over the American system of government. Here is further context. For a more in depth discussion and a great read — upon which much of this blog finds its genesis — look to Ray Raphael’s book Mr. President: How and Why the Founders Created a Chief Executive (2012).

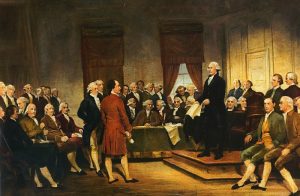

I begin with the delegates. Think of it like this: If you were a wealthy American landowner in the late eighteenth century, and held a position of prominence for some time, you probably wanted to ensure that, whatever government governed, your status remained unchanged. Should not your vote count a little more than someone else? Can we really let the people select of our elected officials?

On these basic questions the delegates to the Constitutional Convention were either conflicted, or outright opposed. As Roger Sherman, the representative from Connecticut proclaimed, “The people immediately should have as little to do as may be about the government. They want information and are constantly liable to be misled.” On the flip side was Alexander Hamilton who touted the “genius of the people” in qualifying the electorate.

Basically, even if a Constitutional Convention delegate agreed to a national government and an “executive branch” to that government, he still had open questions as to what should it look like, how much power it would have, and who would decide the person/persons for such an office.

So how did the delegates get from point A to point B? First, the delegates took the unusual move of calling for secrecy in their debates, something unheard of then and which continues to be a source of confounding discussion even in today’s society; in 1787, and as often argued today, the delegates wanted the freedom to speak freely.

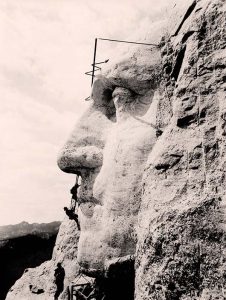

Second, the delegates used England’s King George III as a counter-point to an executive. They wanted no part of a monarchy, or despotic leader, yet needed the executive position to have some teeth so that it would be recognized internationally and complement intra-national needs.