Memory Matters—Recalling Rwanda

“Forgive and forget” — so the saying goes. But in Rwanda, they must forgive yet remember.

Memory matters because:

- The 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi killed more than one million men, women, and children over four months, making the ability to forget both an imp ossibility and an unspeakable betrayal of the victims.

- If Rwanda is to continue to exist, memory must be the prerequisite for creating peace in a country where the genocide’s survivors and perpetrators are neighbors, co-workers and even family members who live side-by-side.

The depths of this powerful dual truth connecting memory and genocide echoes the “never again” commitment following the Holocaust. Ironically, humans and history have yet to learn how to stop repeating deliberate and systematic extermination of others because, tragically, hatred is a lesson that is too often taught successfully.

This past July, I experienced firsthand the power of memory for overcoming hatred and creating peace. I was given the opportunity to attend a four-day conference in Rwanda held in conjunction with the 30th anniversary commemorating the Genocide against the Tutsi. Titled “Listening and Leading: The Art & Science of Peace, Resilience & Transformational Justice,” the event was hosted by Aegis Trust, a global nonprofit that two brothers from England launched in 2000 to keep alive the memory of the Holocaust and other genocides. Today the organization is broadly dedicated to predicting and preventing genocide and crimes against humanity. Why did I go to the Aegis Trust conference?

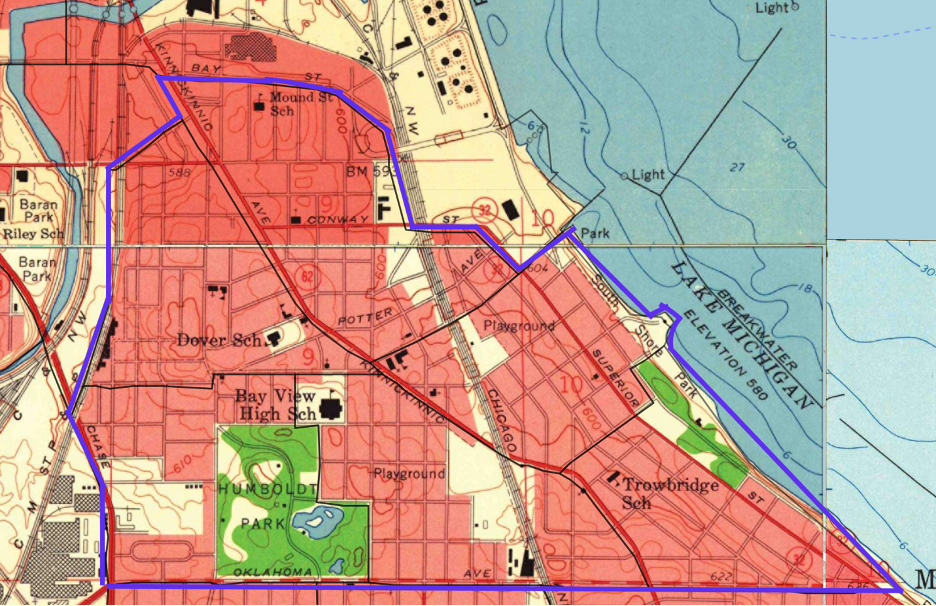

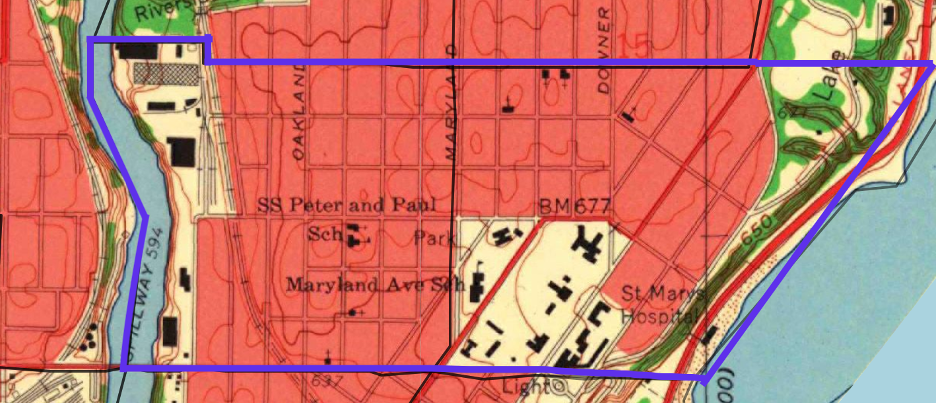

My friend Terri de Roon Cassini, director of the Comprehensive Injury Center and a clinician specializing in trauma care at the Medical College of Wisconsin, received an invitation from Aegis Trust to attend the conference based on MCW’s evolving work in community-based violence prevention in Milwaukee. She invited me to make the 16-hour trip with her colleagues to Rwanda because of my parallel work directing the Andrew Center for Restorative Justice at Marquette University Law School. Restorative justice is partly about remembering so that we can move forward—how acknowledging and responding to harm can lead to healing and safety for those harmed, accountability and compassion for those who harm, and stronger and safer communities.

In that light, I felt compelled to go to Rwanda because its people have something to teach us as Americans grappling with a violence epidemic. Something vital I want to share—especially with those of us in Milwaukee, working to prevent community-based violence. That is my motivation for a series of blogs, beginning with this one that necessarily establishes the sad context of the Genocide against the Tutsi. Captured below is information from the walls of memorial centers, and testimonials from survivors and perpetrators who know all too well that understanding the pathway to genocide is key to prevention.

From peace to hatred

For centuries, 18 different clans constituting the peoples of Rwanda lived peacefully. With a common language, they built a history and culture, sharing and thriving on the rich, fertile hills of their native land in central Africa. But Belgian colonial rule resulting from World War I introduced divisions based on socioeconomic and racial distinctions, categorizing people primarily as Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa. An identity card system initiated in 1932 labeled each person. For three decades, Belgian favoritism of the Tutsi fostered a growing divide. The Hutu widened it after the literal and figurative death of monarchy in 1959, which ushered in Rwandan independence by 1962. Power was in the hands of a highly centralized, single party that created a repressive state with a singular goal: emancipation of the Hutu by exacting revenge against the Tutsi.

Civil unrest became the norm through an incessant propaganda campaign that included elementary school education. Hate speech taught the majority to see the Tutsi as Inyenzi—cockroaches—despite being neighbors, friends, and even family due to generations of intermarriage. Mandates such as the Hutu Ten Commandments dictated absolute rule and superiority of the Hutu while justifying punishment of “traitorous” Hutu who allied with Tutsi or prevented the commandments from being spread as the prevailing ideology.

Hate was effectively learned over the next decades, with the teaching of persecution that included imprisoning, torturing and massacring thousands of Tutsis. By 1973, 700,000 Tutsis were exiled, while thousands of Tutsis and Hutu moderates left Rwanda on their own. Prevented from returning home despite peaceful efforts to do so, many refugees formed a resistance movement known as the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RFP) and invaded Rwanda in 1990.

During the ensuing civil war, the government established internal refugee camps, heightening tension and fear of the Inyenzi. The waralso brought the return of European powers in the form of the United Nations, which tried to negotiate peace with a president who had no control over extremists. Despite hearing of the atrocities, the rest of the world effectively did nothing while all Tutsi were registered via the identity-card system—part of the us-vs.-them impetus of the extremists’ extermination plan designed for ethnic cleansing. This powder keg was lit when the Rwandan president was assassinated on April 6, 1994. The Genocide against the Tutsi was instant and merciless.

Maybe you saw the Don Cheadle film Hotel Rwanda and have a sense of the brutality. Roadblocks went up as militia identified and killed Tutsis. Murderous house-to-house searches led by Hutu extremists armed with machetes, clubs, and guns were widespread. Generations were slaughtered as neighbors, friends, and family members turned on each other. Even women and children were forced to be perpetrators of death and destruction from which no Tutsi was exempt, with Hutu and Tutsi women forced to kill their own Tutsi children. I share the following because we cannot remember what we may not know:

- 10,000 Tutsis were killed daily—seven per minute—over 100 days that wiped out more than one million people.

- 300,000+ children were orphaned while 85,000 children became the heads of their household.

- Homes and infrastructure were demolished; looting, lawlessness, starvation, and chaos were rampant.

- Tens of thousands were tortured, mutilated, and raped, with thousands of widows being intentionally infected with HIV.

The Genocide against the Tutsi eliminated about 1/8 of Rwanda’s population until the RFP was ultimately able to stop the killing in July 1994—without international assistance. Where would Rwanda go from there—and how? Why should the world take note when it turned the other way during the genocide?

Answers lie in the genocide memorial centers and reconciliation villages Rwanda has created to reflect the people and stories behind the stark numbers shared above—the faces that survivors and perpetrators alike knew and the hard truths they lived, the bases for mustering the power of memory necessary to find a way out of violence.

Survivors such as Freddie Mutanguha, CEO, Aegis Trust, and Jesuit priest Rev. Dr. Marcel Uwineza, S.J., capture the country’s current prevailing sentiment from which we all can learn: “To remember is to act so that those criminal activities never happen again. So, to remember is to do justice.”

I seek to do justice by sharing more of what I learned those four days this past July. From survivor care and commemoration to reintegration and reconciliation, my next blog post will take up how memory matters in furthering a hopeful truth that the late South African anti-apartheid activist, politician, and statesman Nelson Mandela once described: “If you can learn to hate, you can be taught to love.”