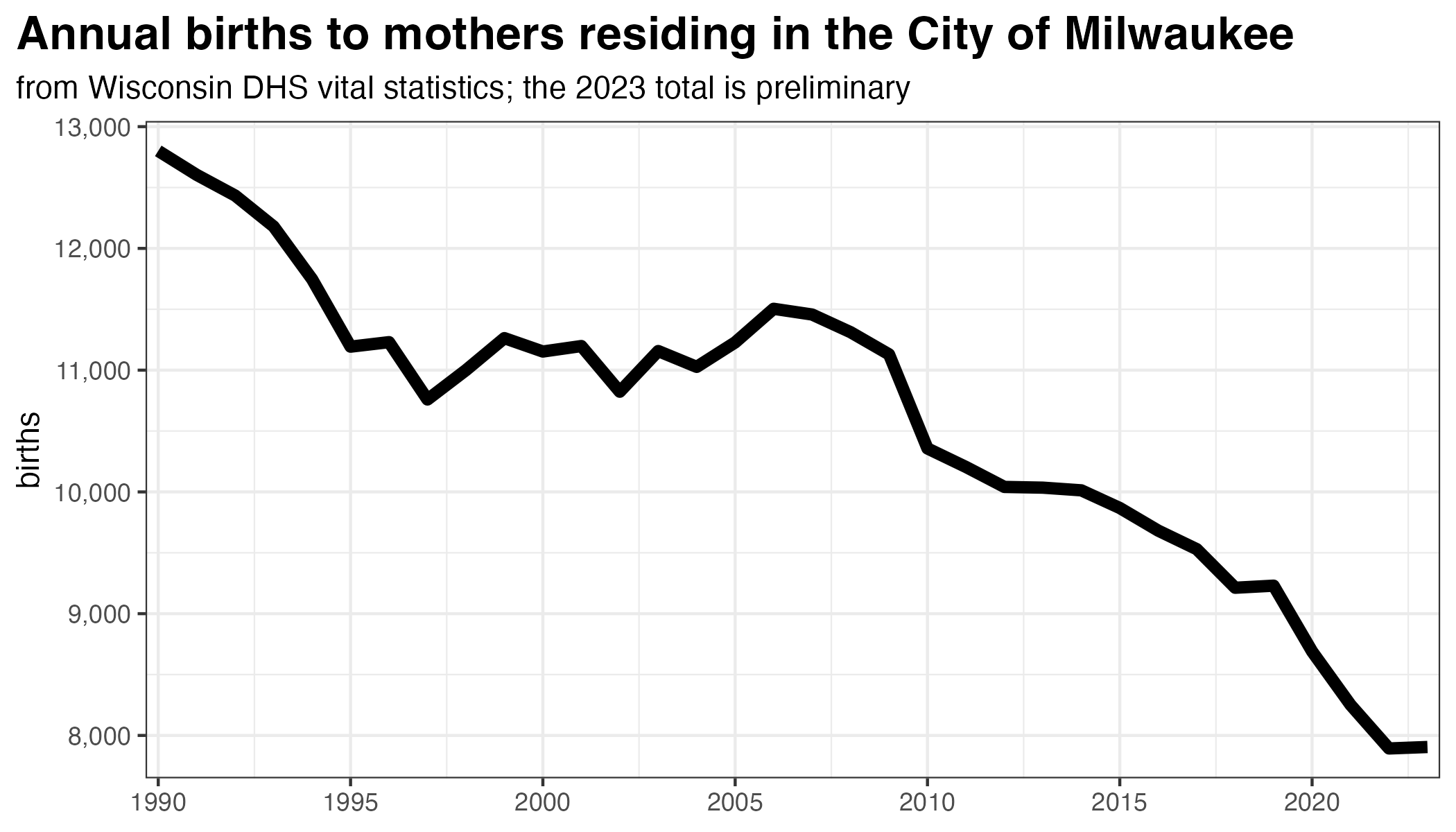

Recent birth counts point to rapidly shrinking school enrollment in Milwaukee

Many things affect a school (or district’s) enrollment, but the most important is simply how many children live there.

In Milwaukee, recent birth trends point to a future of dwindling class sizes, beginning in elementary school and working their way up through the higher grades. Absent a spike in the birth rate or a big change in migration, the three sectors—district, charter, and private—will find themselves fighting over a shrinking pie.

Across the 1990s, the number of babies born fell by 13%. Then, the trend stabilized, even growing slightly, until the Great Recession. 773 fewer babies were born in 2010 than 2009, and annual declines continued after that. From 2009 to 2019, the number of births fell by 17%.

The COVID-19 pandemic caused a drop in births similar to the Great Recession a decade prior. Births fell by 540 in 2020, 439 in 2021, and 358 in 2022. Losses stabilized in 2023, when the preliminary count shows 7,905 births, still 14% lower than prior to the pandemic.

During the 2010s, schools across all sectors reaped the benefits of Milwaukee’s stable birthrate during the 2000s. Many of the twelfth-graders who graduated this year were born in 2006. Since then, the annual number of births has dropped by 31%.

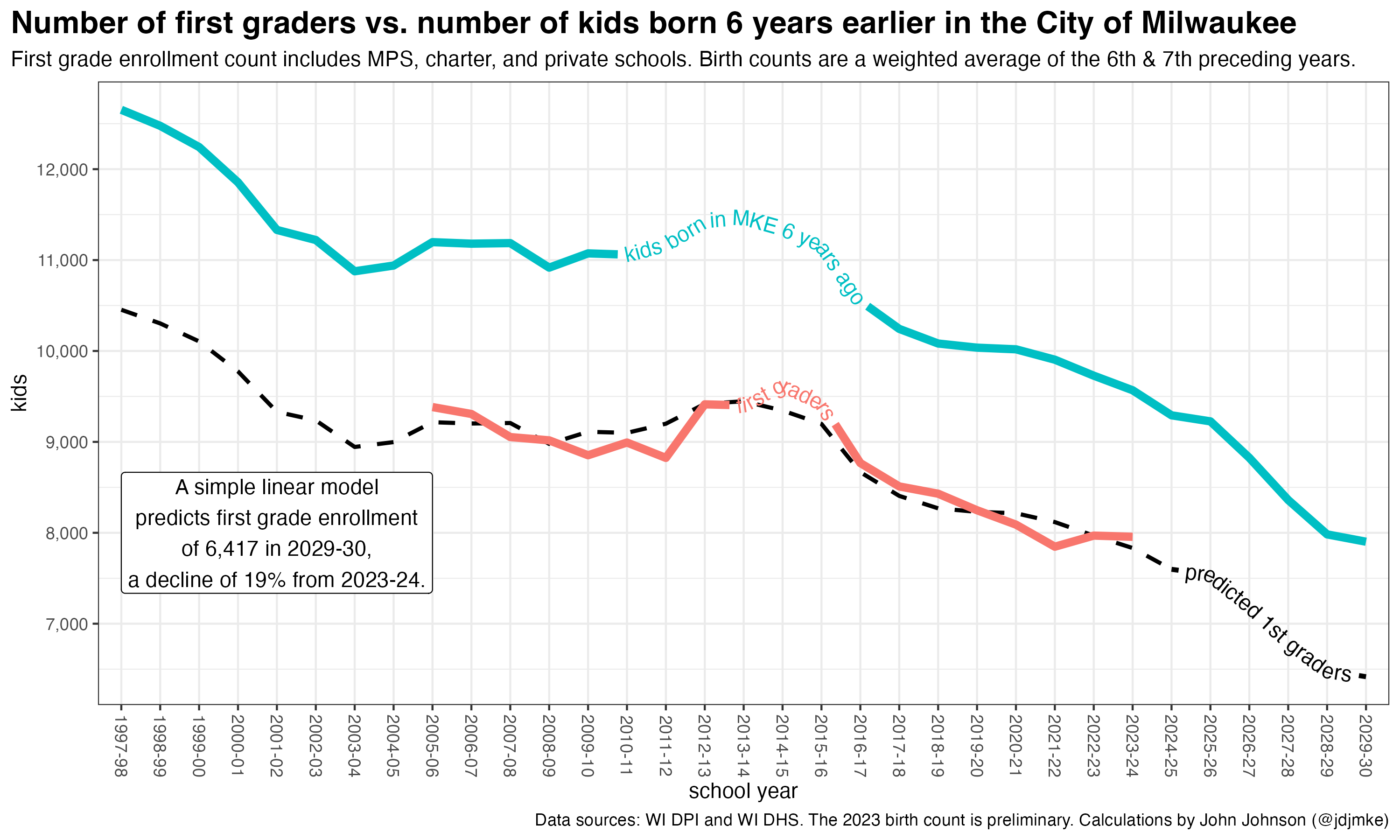

In the next graph, I compare the number of first graders entering any school in Milwaukee (district, charter, or private) with the number of babies born six years prior. Subsequent first grade enrollment is lower than births because more young families move out of Milwaukee than move into it. However, the size of the gap has remained fairly steady across the 19 school years for which I have data.

In every school year, the number of first graders enrolling has been 21% to 15% lower than the number of babies born 6 years ago. In other words, first grade enrollment has always been between 79% and 85% of the total births 6 years prior. In 2023-24, the figure was 83%, and in 2022-23, 81%.

Because of this stable relationship between births and subsequent first grade enrollment, we can use recent births to forecast the size of future first grade classes.

In the 2023-24 school year, 7,956 kids enrolled in first grade at any school within city limits. Six years prior, about 9,568 kids were born in the city. The children who will enroll in first grade in 2029-30 have already been born. In Milwaukee, they number 7,902.

If Milwaukee retains young families at the best rate from our recent past, it would still mean a decline of 16% in the number of first graders over the next 6 years. Retaining families at the worst rate would result in a 22% reduction. The simple linear model I use in the above graph predicts a 19% drop.

Again, these predictions are not based on a forecast of future birth rates; they are based on the number of babies who have already been born. Some combination of retaining more young families and attracting more migrants (domestic and international) could alter this trajectory. But the current path clearly points to a drop of nearly 20% in the number of first graders by the end of the decade. That decline will then work its way through elementary, middle, and high schools over the 2030s.