For four seasons, from 1946 through 1949, American football fans had two major leagues to follow. In addition to the National Football League, there was the All-America Football Conference. Competing head-to-head with the ten-team NFL for fans and players, the AAFC offered a product that was clearly the equivalent of that provided by its older rival.

For four seasons, from 1946 through 1949, American football fans had two major leagues to follow. In addition to the National Football League, there was the All-America Football Conference. Competing head-to-head with the ten-team NFL for fans and players, the AAFC offered a product that was clearly the equivalent of that provided by its older rival.

In this year’s Super Bowl, the two surviving franchises of the AAFC will, for the first time, square off against each other for the championship of professional football.

The AAFC began play in 1946 with eight teams: the New York Yankees, Brooklyn Dodgers, Buffalo Bisons, and Miami Seahawks in the East, and the Cleveland Browns, Chicago Rockets, Los Angeles Dons, and San Francisco 49ers in the West. (These Cleveland Browns are now the Baltimore Ravens.)

In 1947, the Miami team was replaced by the Baltimore Colts, and in 1949, the New York and Brooklyn teams merged (resulting in a seven-team league) while the Chicago team changed its name from Rockets to the Hornets.

After the 1949 season, the two leagues agreed to merge into a single league initially known as the National-American Football League (though the title returned to NFL the following year). Three of the seven AAFC teams—the Cleveland Browns, the San Francisco 49ers, and the Baltimore Colts—were admitted into the NFL, and the AAFC New York Yankees were merged with the NFL’s New York Bulldogs.

Although the combined New York team—which competed against the New York Giants—was owned by the Bulldogs owner, the coach, most of the players, and the team’s name (Yanks) were taken from the AAFC franchise. The other three AAFC teams were folded, and their players distributed to the remaining 13 teams through a draft.

The Baltimore Colts folded after the 1950 season, a decision that reduced the number of NFL teams from 13 to 12. (In 1953, a different, and unrelated, version of the Colts began play in Baltimore.)

The two franchises remaining from the AAFC, the Browns and the 49ers, flourished in the NFL. Those two teams had been by far the strongest teams in the AAFC, with the Browns winning all four league championships while the 49ers finished with the second best record in the league each year. The Browns won the NFL championship in their first year in the league and finished first in their division in each of their first six years in the NFL. While the 49ers could not match that level of excellence, they had winning seasons in four of their first five NFL campaigns.

Of course, in 1996, the Cleveland Browns left Cleveland for Baltimore, where they became the Ravens and subsequently won a Super Bowl in 2000. (Although the NFL persists in the silly claim that the current Cleveland Browns are a continuation of the Browns of the past, all that the current team shares with the Browns of the past is the ownership of the “Cleveland Browns” trademark.) After a couple of unexceptional decades, the 49ers emerged as one of the modern NFL’s premier teams, winning five Super Bowls in the 1980’s and 1990’s.

Although the Browns and 49ers have been in different conferences in the NFL since 1950, this is the first time that they have met for the NFL championship. The closest that they previously came to meeting was in 1990 (following the 1989 season), when the Browns lost to the Denver Broncos in the AFC championship game. Had they defeated the Broncos, they would have played the 49ers two weeks later in the Super Bowl.

They almost met much earlier. In 1953, the 49ers finished one game behind the Detroit Lions in the NFL’s Western Conference while the Browns won the Eastern Conference for the fourth consecutive year. During the 1953 regular season San Francisco lost three games, all by very narrow margins. They lost twice to the Lions, by scores of 24-21 and 14-10, and to the Browns in an inter-conference game, 23-21. Had they won any two of those games, they would have played the Browns for the NFL championship. (Had they won just one, they would have played an additional game with the Lions with the winner playing the Browns for the championship.)

Since the AAFC played its game more than 63 years ago—fittingly the 1949 AAFC championship game in which Cleveland defeated San Francisco, 21-7—it is unlikely that there are large numbers of AAFC fans still around to appreciate the special character of this year’s game, but for those that are, and for students of the history of professional football, this year’s Super Bowl probably seems very significant.

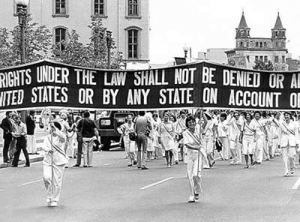

In 1776, as the founders were meeting to form the new government for the nation that would become the United States of America, Abigail Adams wrote to her husband John Adams and asked him “to remember the ladies” while drafting the governing documents. She continued,

In 1776, as the founders were meeting to form the new government for the nation that would become the United States of America, Abigail Adams wrote to her husband John Adams and asked him “to remember the ladies” while drafting the governing documents. She continued,