New Marquette Lawyer Focuses on Efforts to Repair and Respond to Harm

In important but differing ways, the four major stories in the summer 2022 edition of Marquette Lawyer magazine all focus on what can be done to improve things when harm occurs.

In important but differing ways, the four major stories in the summer 2022 edition of Marquette Lawyer magazine all focus on what can be done to improve things when harm occurs.

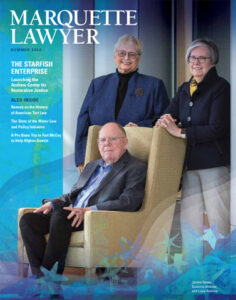

The cover story—featuring the biggest news this past year for Marquette University Law School itself—spotlights a $5 million gift from Marquette alumni, Louie Andrew (L’66) and his wife, Suzanne Bouquet Andrew (Sp’66). The gift has established an endowment enabling the university to create the Andrew Center for Restorative Justice at the Law School. The Andrews have been longtime generous supporters of the Law School, both generally since the tenure of the late Dean Howard B. Eisenberg and, particularly, of the work of Distinguished Professor of Law Janine P. Geske, L’75, an internationally known advocate of restorative justice.

Restorative justice work, broadly speaking, involves bringing together people who have been affected by harmful situations and, through discussions, often in moderated circle groups, seeking ways to reduce the harm. Geske, a former state supreme court justice and trial judge, first took part in restorative justice sessions at the Wisconsin correctional facility in Green Bay. The Andrews became supporters of Geske’s work through the Law School to bring restorative justice principles to bear on a range of major social issues and to hold a series of conferences at the Law School, beginning in 2004.

In recent years, the Law School’s Restorative Justice Initiative, as it was called beginning in 2004, reached a crossroads, on account of factors including the impact of the pandemic and Geske’s retirement. When Geske, the Andrews, and others then determined to renew the work in an enduring way, the Andrews stepped up with their historic donation this past December and Geske agreed to return to the Law School to get the permanent effort launched.

In the new magazine, an article, headlined “Starfish Enterprise,” describes the past path of restorative justice at the Law School—and its anticipated future through the new Andrew Center for Restorative Justice. Click here to read the piece. A companion article, “A Quiet Approach, Resounding Accomplishments,” profiles the Andrews and may be read by clicking here.

The next entry takes up the law’s more traditional (civil) approach to harm. In a new book rich in detail and perspective, Joseph A. Ranney, Marquette Law School’s Adrian P. Schoone Fellow in Legal History, examines legal approaches to civil wrongs and their aftermath—the harms that lead people to turn to courts. That is to say, Ranney writes about the law of torts. The magazine offers excerpts from his new book, The Burdens of All: A Social History of American Tort Law (Carolina Academic Press 2021), and from related pieces by Ranney.

From the early days of railroads to the rise of automobiles and the expansion of product liability law, Ranney describes trends and ideas that have shaped tort law. The magazine piece concludes with observations by Alexander B. Lemann, assistant professor of law at Marquette University, on Ranney’s book. Both Ranney’s collection, “Exploring the Fault Lines,” and Lemann’s comment, “Tort Law’s Past—and Future,” may be read by clicking here.

The third entry in this series takes up a particular, even unique, aspect of the past academic year’s pro bono work—which is, more generally, an important part of life for many Marquette Law School students. During the holiday break this past December and January, 49 law students, nearly 10 percent of the Law School’s enrollment, volunteered to spend time at the U.S. Army base, Fort McCoy, in rural west central Wisconsin. Thousands of people who had been evacuated from Afghanistan during the collapse of the government there in August 2021 had been temporarily settled at Fort McCoy, hoping for, awaiting, new homes in the United States.

The law students did not receive pay or academic credit for their work. But they found satisfaction in the assistance they were able to give the Afghans in getting started on the process of getting permission to stay in the United States permanently. An article in the magazine describes the students’ work and includes comments from five of them on this special way of helping others deal with the harm that had overturned their prior lives. The article, “Helped Today; Gone Forward Tomorrow,” may be read by clicking here.

Finally, dealing with environmental issues and the future of water—indeed, the rise of the administrative state more generally—can also be looked at as a way of responding to harm and potential harm in our society. Since 2014, the Law School’s Water Law and Policy Initiative, part of the broader emphasis on water issues at Marquette University, has addressed important water issues. Led by Professor David Strifling, the initiative has contributed to understanding of subjects ranging from high-tech ways of managing water use to the virtues of using kitchen garbage disposals. The work of the initiative is described in ”Even the Kitchen Sink,” which may be read by clicking here.

To be sure, there is more to the magazine. This includes an encomium of William C. Welburn, upon his retirement as Marquette University’s vice president for inclusive excellence this past academic year, and Dean Joseph D. Kearney’s reflections on the Andrew Center for Restorative Justice and some of the relationships that have moved Marquette Law School forward during the past 130 years. His column, “Let Us Tell You a Story—or Many Connecting Ones,” may be read by clicking here. And, scarcely least, the Class Notes pages succinctly describe recent accomplishments of more than 90 Marquette lawyers and may be read by clicking here.

Summary

Summary