The Cato Institute’s Ilya Shapiro recently spoke at the Law School concerning the status of relaxed state marijuana laws in light of the federal Controlled Substances Act’s continued prohibition of activities that these state laws now allow. This is a timely question with, it turns out, a less-than-certain answer. More precisely, it demands an answer that is more nuanced, and less categorical, than one might initially be inclined to give.

The Cato Institute’s Ilya Shapiro recently spoke at the Law School concerning the status of relaxed state marijuana laws in light of the federal Controlled Substances Act’s continued prohibition of activities that these state laws now allow. This is a timely question with, it turns out, a less-than-certain answer. More precisely, it demands an answer that is more nuanced, and less categorical, than one might initially be inclined to give.

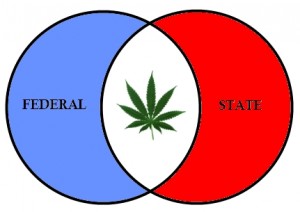

One’s initial answer is likely that these state laws are preempted—that is, rendered void and unenforceable—because of the federal statute. It is conventional constitutional doctrine, after all, that the U.S. Constitution’s Supremacy Clause makes valid federal law supreme over conflicting state law. Moreover, because the U.S. Supreme Court in Gonzales v. Raich (2005) deemed the federal marijuana prohibition to be a valid exercise of Congress’ commerce power, the specific question of whether state marijuana laws are vulnerable to preemption seems already to have been answered.

Mr. Shapiro makes an important observation, however. Drawing on the work of Vanderbilt law professor Robert Mikos, he notes that state decriminalization and even authorization of marijuana possession and use do not necessarily conflict with the federal criminal prohibition. If state officers were in fact responsible for enforcing federal law, or if the federal statute could and did require that state laws include comparable prohibitions, then a different situation would present itself. But state officers cannot be compelled to enforce federal law, and the federal statute does not require—and likely could not mandate—that state laws contain comparable marijuana prohibitions.

It’s not that the state laws are attempting to nullify the Controlled Substances Act. The federal statute still applies to the activities that it specifies, is still enforceable by federal agents, and can still lead to federal prosecutions, convictions, and sentences. It is simply that the states themselves are no longer criminalizing some of these activities. And while that may disappoint federal expectations, and even conflict philosophically with the federal outlook, that circumstance by itself does not give rise to preemption under the Supremacy Clause.

Of course, individual users, growers, and suppliers, among others, need to be aware that they are still subject to the federal prohibition. Also, those who meaningfully facilitate or encourage the federally prohibited activities of these individuals need to be aware that they could be aiding or abetting a federal crime, which is unlawful under 18 U.S.C. § 2. Indeed, a state that does more than simply permit marijuana-related activities—e.g., facilitating the provision of marijuana to users—could be subjecting its officers to potential federal criminal liability as well. And if a state were actually to engage in the cultivation and sale of marijuana, then this would violate the Controlled Substances Act outright.

Whether Congress will maintain a posture of benign neglect in the face of increasingly numerous medical marijuana laws—roughly eighteen states at present—remains to be seen. The recent legalization of recreational marijuana in Colorado and Washington, for example, may be enough to prompt federal legislative action, particularly if other states follow suit. However, to the extent that Congress cannot compel states to reenact their prohibitions by means of a punitive mandate under the Commerce Clause, Congress would need to explore other options, such as its power under the Spending Clause. Using an arrangement called conditional spending, Congress may condition a state’s receipt of federal funds on the fulfillment of certain obligations, as long as the obligations are explicit and relate to the purpose of the funds and as long as the funding dynamic is such that states have a genuine choice to accept or forgo the money, and with it the conditions.

The issues raised by Mr. Shapiro and Professor Mikos are certainly timely, important, and deserving of serious consideration. They are relatively underdeveloped in the case law and academic literature, making them an inherently fruitful object of scholarly examination. Given their stage of development, moreover, they are also open to critical inquiry from a variety of perspectives and interpretive approaches. Lastly, they have the potential to extend well beyond the field of marijuana laws, from other drug laws to firearms.

Further Reading

Todd Garvey, Medical Marijuana: The Supremacy Clause, Federalism, and the Interplay Between State and Federal Laws (Congressional Research Service, Nov. 9, 2012).

Robert A. Mikos, On the Limits of Federal Supremacy—When States Relax (or Abandon) Marijuana Bans, Cato Institute Policy Analysis No. 714 (Dec. 12, 2012).

Robert A. Mikos, On the Limits of Supremacy: Medical Marijuana and the States’ Overlooked Power to Legalize Federal Crime, 62 Vanderbilt Law Review 1421 (2009).

Robert A. Mikos, A Better Approach to Preemption in Medical Marijuana Cases, 16 Journal of Health Care Law & Policy (forthcoming 2013).

Enjoyed the article re the Supremacy Clause and agree that the Federal government cannot compel state officers to enforce Federal statutes. However, I believe that State officers can enforce Federal statutes of their own volition under 18 USC 3041 if they choose to do so. Each state officer takes an oath to support the U.S. Constitution as well as the state Constitution. It would be interesting to see what the legal outcome would be in such a case involving a state that has permitted recreational marijuana use.

Dean Collins

Police Commander, (ret.)

Milwaukee Police Dept.

Whether its government mandating a catholic church to provide birth control,

Whether its government mandating you buy health insurance;

Whether its the government trying to limit your right to bear arms

Whether its a government and church ignoring the very first few verses of Genesis and prohibiting a creation that God told man to use and enjoy:

LEGALIZE FREEDOM

The reasoning appears sound. Garden Grove v Felix Kha found that the feds CANNOT use state cops to enforce federal law. (And as the feds have only 5,500 men and make just 1% of all marijuana arrests that doesn’t sound too good for the longevity of the prohibition. lol)

However the big question here is why does the federal government feel so obliged to continue the failed and deadly marijuana prohibition?

Recent polling found that the American people support legalizing marijuana like wine to the tune of 52% (for) to 45% (against). Since the will of the people is for legalization, then what can it possibly be that causes the federal government to feel so obliged to keep marijuana illegal? We should NOT have laws that create more harm than what they prevent! ..and that is exactly what the federal marijuana prohibition does.

I enjoyed the analysis, I’m actually surprised there aren’t anymore people to share input. As I was analyzing the fact pattern, and currently a student in a paralegal program, I can’t help but wonder why the Supreme Court initiate a legal question for procedural rules over this state jurisdiction. Welcome any persons thoughts!