Part Three of a series on Election Law, providing context to our system of government, our election process and a little history to evaluate and consider in the candidate-debate. Prior blog posts discussed the lead-up to the Constitutional Convention of 1787 and provided context to the debate over the American system of government. Here is further context. For a more in depth discussion and a great read — upon which much of this blog finds its genesis — look to Ray Raphael’s book Mr. President: How and Why the Founders Created a Chief Executive (2012).

Part Three of a series on Election Law, providing context to our system of government, our election process and a little history to evaluate and consider in the candidate-debate. Prior blog posts discussed the lead-up to the Constitutional Convention of 1787 and provided context to the debate over the American system of government. Here is further context. For a more in depth discussion and a great read — upon which much of this blog finds its genesis — look to Ray Raphael’s book Mr. President: How and Why the Founders Created a Chief Executive (2012).

I begin with the delegates. Think of it like this: If you were a wealthy American landowner in the late eighteenth century, and held a position of prominence for some time, you probably wanted to ensure that, whatever government governed, your status remained unchanged. Should not your vote count a little more than someone else? Can we really let the people select of our elected officials?

On these basic questions the delegates to the Constitutional Convention were either conflicted, or outright opposed. As Roger Sherman, the representative from Connecticut proclaimed, “The people immediately should have as little to do as may be about the government. They want information and are constantly liable to be misled.” On the flip side was Alexander Hamilton who touted the “genius of the people” in qualifying the electorate.

Basically, even if a Constitutional Convention delegate agreed to a national government and an “executive branch” to that government, he still had open questions as to what should it look like, how much power it would have, and who would decide the person/persons for such an office.

So how did the delegates get from point A to point B? First, the delegates took the unusual move of calling for secrecy in their debates, something unheard of then and which continues to be a source of confounding discussion even in today’s society; in 1787, and as often argued today, the delegates wanted the freedom to speak freely.

Second, the delegates used England’s King George III as a counter-point to an executive. They wanted no part of a monarchy, or despotic leader, yet needed the executive position to have some teeth so that it would be recognized internationally and complement intra-national needs.

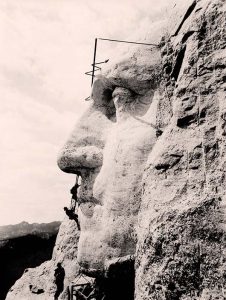

They had a good choice for the position in George Washington, who presided over the Convention yet spoke very little.

They had many tools at their disposal in terms of the position — i.e. points to discuss and decide — such as the length of the position (perpetual versus limited terms), compensation, making it a single versus multi-head position, veto-powers, etc.

They even debated over what to call the position — monarchy vs. presidency vs. magistracy — as no one knew, and a title can influence perception as much as reality can.

Indeed, fashioning an executive position from whole cloth is much different than stitching together a nearly complete garment, and, in this case, the emperor needed new clothes.

And yet, underlying all of these debate points was an overarching problem: how would the position be chosen?

On this point, the debate continued for months. Should the presidency be “independent” and not beholden to Congress (that is, let the people decide)? Or should the people’s choice in representation have the right to choose the position (that is, let Congress decide)?

With neither alternative unanimous (once again, the debate between state-rights versus federal-rights was at issue) an entirely different scheme of indirect representation was proposed through a complicated process of electors. Rather than a direct decision by the legislative branch or the people, a group of citizens from each state (the electors) would choose the executive branch head.

The theory was one of compromise; if the people cannot be trusted but need to be involved, at least they can indirectly participate in choosing the President — or at least that is how the theory went.

After months of debate, this indirect election made its way to the “Committee of Eleven”, an aptly named committee charged with drafting the final document based upon the agreement of delegates. By no means was agreement unanimous when the drafting began. Instead, just as in today’s practice of drawing up contracts or agreement, the principals agreed to a general outline and assigned the drafting “laboring oar” to committee; the devil was in the details.

On Tuesday, September 4, 1787, the Committee of Eleven reported its findings. Among those reported was the “Electoral College” (a name not found in the Constitution itself but so named years later) where each state would select “electors” equaling the total of its senators and congressmen, and the electors would choose the presidency. If no candidate achieved a majority of electoral votes, the matter was then thrown to Congress to choose.

The elector-plan was untested.

The elector-plan was a compromised solution.

After continued discussion, the elector-plan was retained in the final draft.

Of course, when it came to the Constitution’s final draft, objections remained — including those of Benjamin Franklin:

I confess that I do not entirely approve of this Constitution at present, but Sir, I am not sure I shall never approve it: . . . In these Sentiments, Sir, I agree to this Constitution, with all its Faults, if they are such; because I think a General Government necessary for us, and there is no Form of Government but what may be a Blessing to the People if well administered; and I believe farther that this is likely to be well administered for a Course of Years, and can only end in Despotism as other Forms have done before it, when the People shall become so corrupted as to need Despotic Government, being incapable of any other. . . . I doubt too whether any other Convention we can obtain, may be able to make a better Constitution . . . . Thus I consent, Sir, to this Constitution because I expect no better, and because I am not sure that it is not the best. (from the notes of James Madison)

The next step was ratification, a process of sending the Constitution to the individual states for their debate. Only upon ratification would the Constitution become law.

And from there, the rest is history. By the end of July 1788, 11 of the 13 states ratified the new Constitution; the President would be selected in early 1789 and the new government in place by March, 1789.

So how has the Electoral College worked in practice — see my next post, The School of Electoral College.

I look forward to your next post, “The School of Electoral College.” The candidate elected as President in the November general election may challenge the Electoral College in its vote. The Electoral College has no federal and only a few state mandates to vote for the candidate awarded the electoral votes. A state’s Electorate, usually chosen by their political party, may be in a dubious position if their party has voiced non-support of their elected candidate. Their vote may be more crucial than a “rubber stamp” vote which, in the past, was the common and usual practice.