Alexis de Tocqueville was a French aristocrat sent by his country to inspect American penitentiaries during the 1830s. He dutifully delivered his report, but he also found himself interested in more than penitentiaries. In Democracy in America (1835), he provided a wide-ranging and to this day highly regarded account of life in the youthful, rambunctious American Republic. Somewhat surprisingly, de Tocqueville discussed at length the role and function of jury duty.

Although de Tocqueville recognized the jury as a “juridical institution,” that is, a body that renders verdicts, he was more interested in the jury as a “political institution.” He argued that the jury “puts the real control of affairs into the hands of the ruled, or some of them, rather than into those of the rulers.” The jury was a vehicle through which the citizenry could exercise its sovereignty.

What’s more, jury duty struck de Tocqueville as a “free school.” “Juries, especially civil juries,” he thought, “instill some of the habits of the judicial mind into every citizen, and just those habits are the very best way of preparing people to be free.” As a form of “popular education,” jury duty offers practical lessons in the law and teaches jurors their rights under the law.

Overall, de Tocqueville was pleased Americans took eagerly to jury duty and felt robust, active juries were extremely important in the success of the nation. Jury duty, he said, “makes men pay attention to things other than their own affairs” and thereby “combat that individual selfishness which is like rust in society.”

How disappointed de Tocqueville would be learn how people perceive jury duty in the present. While people who actually serve on juries tend to say their experiences were positive ones, a huge percentage of Americans dread receiving a summons for jury duty and do their best to avoid serving. Websites such as “How to Get Out of Jury Duty” and “10 Ways to Avoid Jury Duty” are popular.

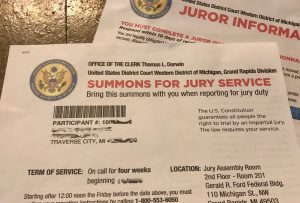

In the average year, approximately 32 million Americans are summoned, but only 8 million report. One-eighth of the summons cannot be delivered, and another one-sixteenth of those summoned simply fail to show up. Many others seek and obtain waivers, exceptions, and exemptions, with reasons ranging from economic hardship and limited English to felony convictions and studying for a bar exam. Some of the claims are pure and true, but many are not.

No single reason explains the contemporary aversion to jury duty, and for some it is just a gut reaction. Surveys have found that people who are summoned cite two major reasons for their reluctance to serve: (1) juries do not make a difference and (2) jury duty is inconvenient.

Why has jury duty become burdensome and uninspiring? What has caused the idea of serving on a jury to plummet since de Tocqueville’s time? The jury itself, in my opinion, is not the primary reason for the decline. The issue is the type of society in which the jury functions. We have evolved from a young, eager democracy full of people on the make into a mass society in which community ties are weak and ennui is widespread and even stylized. In a society of this latter sort, jury duty has difficulty finding and holding its place. Jury duty strikes many as irrelevant and annoying.

The history of American juries seems filled with cross-currents. Alschuler and Deiss, A Brief History of the Criminal Jury in the United States, 61 Chicago Law Rev. 867 (1994), note that in many states only tax-paying white men qualified as jurors but also suggest that it was commonplace to draft courthouse bystanders, who were often unemployed and uneducated, as jurors. The use in current times of well-financed jury selection tactics suggests that jury selection sometimes becomes the judicial branch counterpart of legislative gerrymandering. See generally Anderson, Peremptory Challenges at the Turn of the Nineteenth Century: Development of Modern Jury Selection Strategies as Seen in Practitioners’ Trial Manuals, XVI Stanford J. of Civil Rights & Civil Liberties 1 (2020). Ken Luce, the distinguished Marquette law professor, used to say that the first maxim of equity in the courts of Chicago is that justice prevails when the fix is even. Perhaps that is equally true of gerrymandering and jury selection. And perhaps jury duty seems irrelevant and annoying to many because of the gaming in the system, and because many are called but few are chosen.

Yes, in de Tocqueville’s time the great majority of Americans were ineligible for jury service. Women, slaves, so-call “free Negroes,” and indigenous people could not serve, and only white men were called for jury duty. One suspects the latter were the people de Tocqueville took to be genuine Americans. Later in time, we have of course come to recognize the racist, patriachal character of democracy in the Early Republic.