[This is the second in series of posts summarizing my new article, “The Grapes of Roth.” Here is the introduction.]

Why did courts become enamored with the inane verbiage of the “total concept and feel” test in the 1980s? The story starts with Learned Hand.

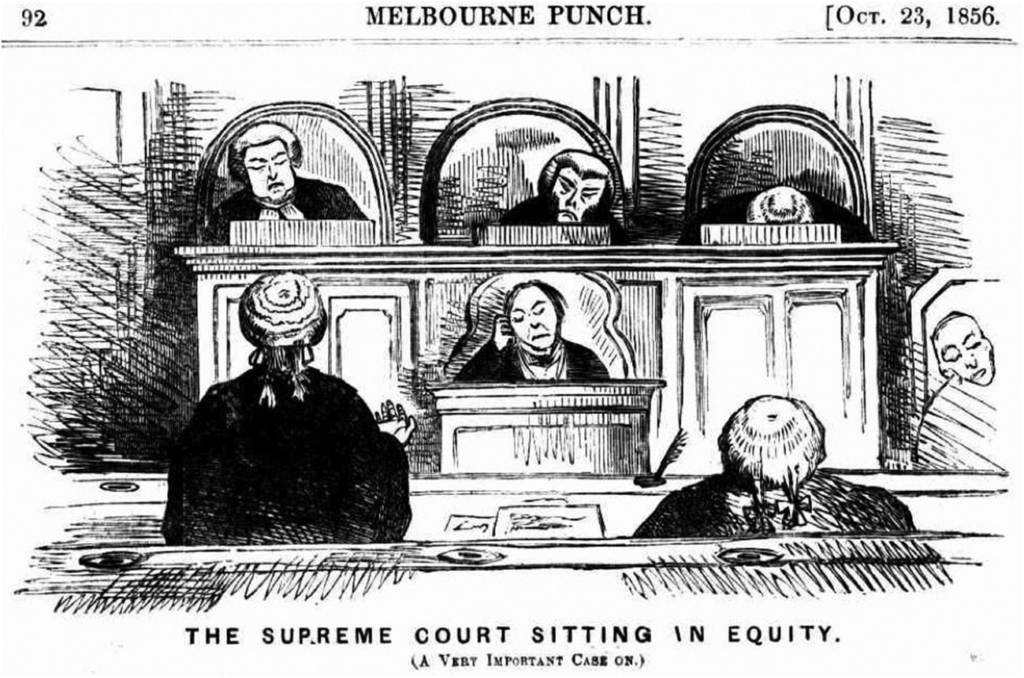

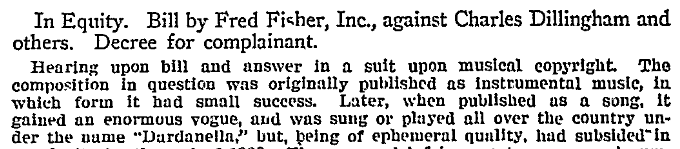

Learned Hand, as I’ve mentioned before, is one of the giants of copyright law. His opinions in Nichols v. Universal Pictures, Sheldon v. Metro-Goldwyn, and Peter Pan Fabrics v. Martin Weiner have been mainstays in copyright textbooks and cited in caselaw and treatises for decades. But one of the reasons why is not often appreciated. Take a look at any copyright decision from Hand’s heyday, such as his district court opinion in Fred Fisher v. Dillingham (S.D.N.Y. 1924):

The most important line is the first: “In Equity.” Up through 1938, when the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure were adopted, and even for decades after that time, judges were used to resolving certain disputes based on considerations of fairness and justice — suits brought in equity. Not just any claim could be filed in equity; the complainant had to be requesting some sort of relief that was not available to them “at law,” either because that relief was only equitable (discovery, injunctions, rescission, etc.) or because there was some sort of gap or loophole in the law that needed filling. The judge hearing a dispute in equity would resolve the issue without a jury and based on principles of fairness, such as those encapsulated in the maxims of equity.

Most copyright cases–indeed, most intellectual property cases–before 1938 were brought in equity, because typically the primary relief being sought was an injunction. Indeed, well after the merger of law and equity in 1938, courts still heard copyright cases claiming injunctive relief in an equitable fashion, without a jury; and even after the Supreme Court nixed that practice whenever damages were alleged in 1959’s Beacon Theatres v. Westover, juries were rarely requested in copyright cases until the 1980s. The result was that throughout the middle decades of the twentieth century, judges were quite used to making infringement decisions on their own, based on their impressions of the two works at issue.

This was in many ways fortunate, because an infringement determination in non-exact copying cases involves a tricky balance of three disparate inquiries. First, there is a question of amount: how much of the plaintiff’s material wound up in the defendant’s work? Second, there is a legal determination to be made: was the borrowed material the sort that the law should categorize as protected? And finally, there is a question of line-drawing: where is the threshold of impermissible borrowing, and did the defendant cross it?

The first of these questions is more or less factual, although determining whether how much a defendant’s non-identical character or melody or painting is based on the plaintiff’s is the stuff of many late-night pop culture arguments. (Is Battlestar Galactica 1978 derivative of Star Wars? How much?) The second question is mostly legal, and no less difficult. Factual material is not protected, and neither are the general ideas or concepts underlying a work. But where’s the boundary between a fact (not protected) and how it’s expressed (protected)? What is the expression in a work (protected) and when does it become so abstract or common that it becomes a mere idea (unprotected)? For example, take photographs:

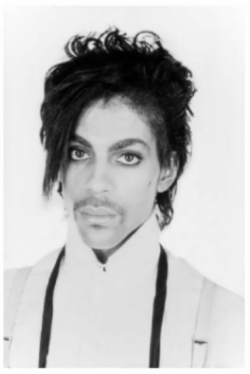

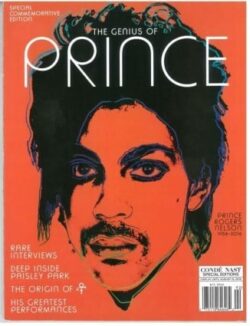

Obviously Prince’s face is not something the photographer created and she can’t claim protection over it — Prince’s face is a sort of fact. But the artistry that the photographer added is copyrightable. What is it, exactly? And how much of the artistry, and not merely the features of Prince’s face, is duplicated in the Warhol artwork below?

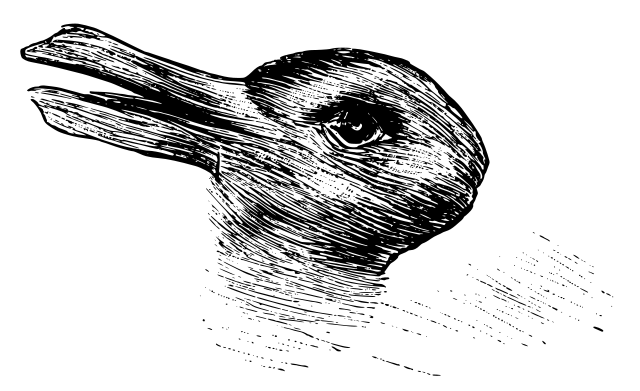

These two questions — the amount taken, and its protectability — are hard to consider simultaneously. Focus on the total amount of similarities and dissimilarities, and their protectability fades from view. Focus on the protectability of various pieces of the plaintiff’s work, and the total amount taken becomes blurry. It’s a bit like the old duck-rabbit image popular in introductory psychology courses:

You can see the duck, or you can see the rabbit, and maybe you can rapidly shift back and forth, but unless you have super-human perception or you are utterly unfamiliar with animals you can’t see a “duck-rabbit.”

So the first two questions are difficult to answer together. But it’s also impossible to disentangle them. The amount question and the protection question cannot be tackled seriatim, but rather have to be considered at once in order to answer the third question: has the defendant taken enough protectable material to be liable for infringement? That third question is in some ways the most difficult of all, because it is neither a factual question nor a legal question, but a policy question: how much taking of protected material from the plaintiff’s work is too much? When does it become unreasonable?

Policy questions involving reasonableness calculations might be ideal for a jury to determine, but not only is it not possible to take on the three questions one at a time, it’s also not possible to assign them neatly to different decisionmakers. Copyrighted material cannot simply be separated out like gold ore from silt. Both the precise details of a work, such as lines of dialog, and its higher-level structure, such as a novel’s plot, can be copyrightable. A judge could not therefore itemize every protected or unprotected component of a work for a jury. Indeed, determining whether the defendant took protected material depends on exactly how the defendant copied it — isolated phrases or pages of text; the general conceit or every beat of the narrative. The amount of appropriation depends on what is protected, and what is protected depends on the amount of appropriation.

Judges in the Learned Hand era resolved the question of infringement by making all of the judgement calls at once, in one fell swoop. They announced these decisions with all of the explanatory detail that a football referee provides when they are is trying to determine if a receiver both completed the catch and made a “football move” before dropping it. In other words, “fumble” or “incomplete.” Here’s Hand himself in his classic opinion in Sheldon v. Metro-Goldwyn Pictures (2d Cir. 1936), involving an infringement claim against the Joan Crawford film “Letty Lynton.” After summarizing the plaintiff’s play, the historical event on which it was based, the historical novel that the defendant’s film was allegedly based on, and the defendant’s film, Hand concluded that there were a number of similarities traceable only to the plaintiff’s play, e.g.: “Each heroine’s waywardness is suggested as an inherited disposition; each has had an errant parent involved in scandal; one killed, the other becoming an outcast.” As to why such seemingly general similarities amounted to infringement of protected expression, Hand wrote only that “the dramatic significance of the scenes we have recited is the same, almost to the letter.” Case closed.

Hand’s well-known Nichols opinion is similar. Nichols involved another play-to-film infringement claim, this time that Universal Pictures had ripped off the plot and characters of the plaintiff’s hit play, “Abie’s Irish Rose,” to make their silent film, “The Cohens and the Kellys” (described in some ill-advised ad copy as “The Abie’s Irish Rose of the screen!”). Hand famously spends some time talking about how general ideas are not infringing even if copied, and how some characters in a work have sufficient detail to be copyrightable whereas others don’t. Then it’s time for the “Application” part of the IRAC analysis (as I tell my students, the “A” is what you get paid for!), where Hand concludes, “In the two plays at bar we think both as to incident and character, the defendant took no more — assuming that it took anything at all — than the law allowed.” Why? “The stories are quite different.” Hand then identifies several differences. “The only matter common to the two is a quarrel between a Jewish and an Irish father, the marriage of their children, the birth of grandchildren and a reconciliation…. [T]here is no monopoly in such a background…. [S]o defined, the theme was too generalized an abstraction from what she wrote. It was only a part of her ‘ideas.'” Why ideas and not protected material? Not only does Hand not explain why the material in question is unprotected, he insists that it’s unexplainable: “Nobody has ever been able to fix that boundary, and nobody ever can.”

Nor is this some sort of quirk about Learned Hand. Copyright opinions from the 1900s through the 1950s bore this sort of decision-making style. For example, in Nikanov v. Simon & Schuster (2d Cir. 1957), future Supreme Court justice Potter Stewart affirmed a district court’s finding that the defendant’s Russian language textbook infringed on the plaintiff’s explanatory chart, holding that “[w]hile only a part of the plaintiff’s copyrighted work was appropriated, what was taken was clearly material.” As to whether the taken portion constituted idea or expression, Stewart held by copying the “arrangement, order of presentation and verbal illustration” of a portion of the chart, “more than mere idea” was taken. Why more? It just seemed that way to the court. “This case is perhaps close to the borderline, but no closer than many others in which copyright protection has been afforded.”

Similarly, in Universal Pictures v. Harold Lloyd Corp. (9th Cir. 1947), the defendant imitated a comedy sequence from the 1932 Harold Lloyd film “Movie Crazy” in which the main character, at a dining establishment, is accidentally given a magician’s coat instead of his own. This extended gag ran on long enough to amount to 20% of the original 84-minute film. According to the Ninth Circuit, the defendant’s scene was similar enough to be infringing despite several differences: “Mere observation would illustrate the resemblance without any effort of dissection,” and “[s]light difference and variations will not serve as a defense.” And even though various bits of it had been done before it was still copyrightable: “The originality was displayed in taking commonplace material and acts and making them into a new combination and novel arrangement which is protectable by copyright.”

For better or worse, judges decided non-identical infringement claims in the early to mid-twentieth century by comparing the two works as an ordinary observer would and then mentally paring down the similarities to compare only protected expression, at the end making some judgement about whether the similar and protected material was significant enough to result in liability for the defendant. All that came screeching to a halt in the 1960s, when judges started concluding that this method of decision-making was not sufficiently “law-like.”