The Legal Process Sea-Change

There’s an old joke about scientific progress: that science advances one funeral at a time. The same might be said about judicial philosophies. Some judges might be persuaded to change their views over time, but it is just as likely, if not more, that change occurs through a changing of the guard. So it was with the Second Circuit in the 1960s. The Second Circuit had had a remarkably stable bench during the 1940s, when Learned Hand was the chief judge. Four of them, Hand, Hand’s cousin Augustus, Harrie Chase, and Thomas Swan served together in active or senior status for twenty-five years, from 1929 to 1954. The remaining two, Charles Clark and Jerome Frank, were with them from 1940 on.

There’s an old joke about scientific progress: that science advances one funeral at a time. The same might be said about judicial philosophies. Some judges might be persuaded to change their views over time, but it is just as likely, if not more, that change occurs through a changing of the guard. So it was with the Second Circuit in the 1960s. The Second Circuit had had a remarkably stable bench during the 1940s, when Learned Hand was the chief judge. Four of them, Hand, Hand’s cousin Augustus, Harrie Chase, and Thomas Swan served together in active or senior status for twenty-five years, from 1929 to 1954. The remaining two, Charles Clark and Jerome Frank, were with them from 1940 on.

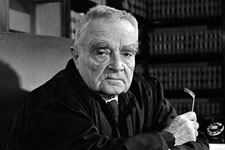

But within six years in the 1950s, the active bench of the Second Circuit experienced nearly a complete turnover, except for Clark. The new judges, who included Henry Friendly, J. Edward Lumbard, Irving Kaufman, and Thurgood Marshall, obviously had different educational and professional experiences from those of the judges they replaced. What truly distinguished the new group, however, is that they had a very different approach to judicial decisionmaking, and in particular the proper role of discretion. No longer were the Second Circuit judges comfortable with leaving important substantive decisions on the merits of a claim to case-by-case equitable balancing. In the 1960s, the Second Circuit began crafting multi-part tests to replace the vague standards that had come before, to force lower courts and later panels to elaborate the reasons for their decisions. Whether they consciously subscribed to it or not, the new judges were heavily influenced by Legal Process ideology.