Minimizing the Risk of Lead Intake at Schools

It might come as a surprise to learn that federal law does not require public or private schools to test their drinking water sources for lead or for any other contaminant. Instead, the Safe Drinking Water Act operates by regulating the “public water systems” that deliver water to the schools. Too often, this broad focus on public systems overlooks the potential contamination sources on private (or school) property, such as lead service lines and indoor lead plumbing “fittings”—valves, bends, and the like. This gap in federal law presents an important opportunity for state intervention.

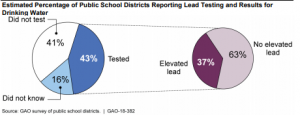

Indeed, the loophole has already led to some disturbing results. In Detroit, for example, officials found unsafe lead and copper levels at 57 of 86 schools tested. Testing in Vermont recently revealed lead contamination in over a dozen schools. And here in Milwaukee, testing showed high lead levels at 183 of Milwaukee Public School’s 3,000 drinking fountains, and at 28 of 425 water outlets tested at charter schools. Worse yet, a recent federal report shows that more than half of public school districts don’t test their water for lead at the point of delivery. Those that did test often found elevated levels of lead, as illustrated in the report’s summary figure: