African-American lawyers were a scarce commodity in 1930.

African-American lawyers were a scarce commodity in 1930.

A recent post on the ConLawBlog posed the question of how many African-American lawyers there were in the United States in 1930. This is a subject that I have been studying for some time, and thanks to a heads up from Professor Idleman, I was able to answer the question.

According to the U.S. Census, in 1930, there were only 1247 black lawyers in the entire United States in 1930, out of a total number of 160,605 lawyers. Of the 1247, 1223 were male and only 24 were female.

Even though the Great Migration had begun after World War I, the bulk of the African-American population still lived in the South in 1930. However, thanks to racial prejudice and limited economic opportunities below the Mason-Dixon line, a significant majority of black lawyers lived outside the South.

The largest concentrations of black male lawyers was in Illinois, which had 187 male African-American attorneys.

Other states with significant numbers were New York (117); Ohio (94); Michigan (63); and Indiana (62). The only Southern jurisdictions with comparable numbers were the District of Columbia (94); and Virginia (57).

Complete state-by-state breakdowns for the 24 females are not provided in the published Census Reports for 1930. The largest number of black female lawyers appears to have been in the District of Columbia, where there were four.

As a percentage of total lawyers, black male lawyers accounted for more than 2% of total male lawyers only in the District of Columbia (2.8%) and Virginia (2.4%). If female lawyers are included — and the number of female lawyers in those two jurisdictions is available — the percentage of black lawyers in each of those two jurisdictions actually goes up slightly, but was still less than 3%.

Nowhere was the absence of black lawyers in 1930 more shocking than in the Deep South. In spite of the large black population, proportionately much larger than it is today, Alabama had only 4 black lawyers, while Mississippi, Louisiana, and Florida had only 6, 8, and 10, respectively. The totals for Georgia and South Carolina were just 14 and 13.

Black lawyers were more numerous in the other former Confederate states, but only slightly: North Carolina (27), Tennessee (26), Arkansas (16), and Texas (20).

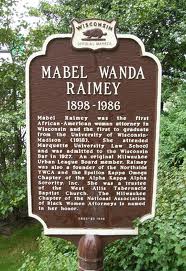

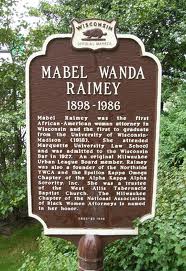

Not surprisingly, given the small pre-World War II black population of Wisconsin, black lawyers were scarce in the Badger State. According to the 1930 Census, there were only three black male lawyers in Wisconsin in 1930, although there was also at least one black female attorney, former Marquette law student Mabel Raimey. (The three black male lawyers included law partners George Heriot DeReef, A.B. Nutt, and James Weston Dorsey, and Ambrose B. Nutt, all of Milwaukee.)

By way of comparison, Minnesota had 11 black lawyers in 1930, while Iowa had 7. North and South Dakota had none.

When the Wisconsin Supreme Court declined in February to grant the Civil Gideon petition and its proposed requirement that legal counsel be appointed for impoverished civil litigants, it instead noted a familiar fallback solution: pro bono initiatives. When Congress decided in 2011 to drastically cut funding for the Legal Services Corporation, which funds legal services providers such as Legal Action of Wisconsin, the message was similar: lawyers should do more pro bono.

When the Wisconsin Supreme Court declined in February to grant the Civil Gideon petition and its proposed requirement that legal counsel be appointed for impoverished civil litigants, it instead noted a familiar fallback solution: pro bono initiatives. When Congress decided in 2011 to drastically cut funding for the Legal Services Corporation, which funds legal services providers such as Legal Action of Wisconsin, the message was similar: lawyers should do more pro bono.

African-American lawyers were a scarce commodity in 1930.

African-American lawyers were a scarce commodity in 1930.