This post is part 2 of a 3-part series based on data originally presented at the first Milwaukee Area Project conference. Part 1, overviews trends in population, employment, and wages since 1990. Part 3, considers the future of the Milwaukee area workforce.

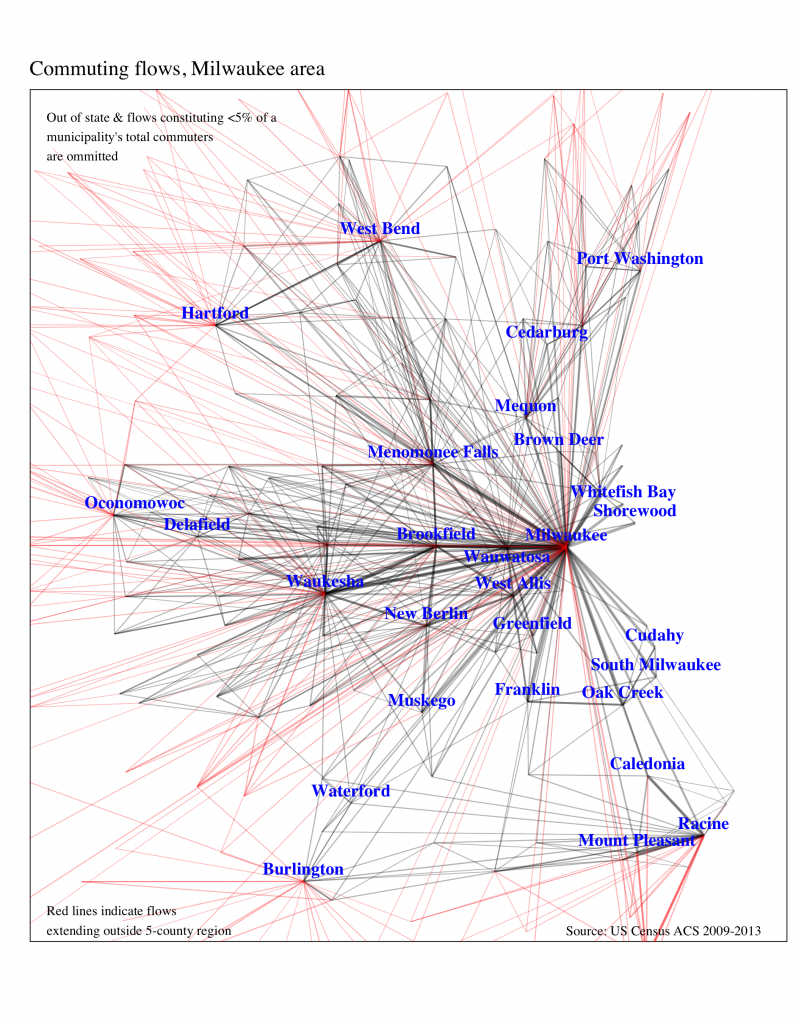

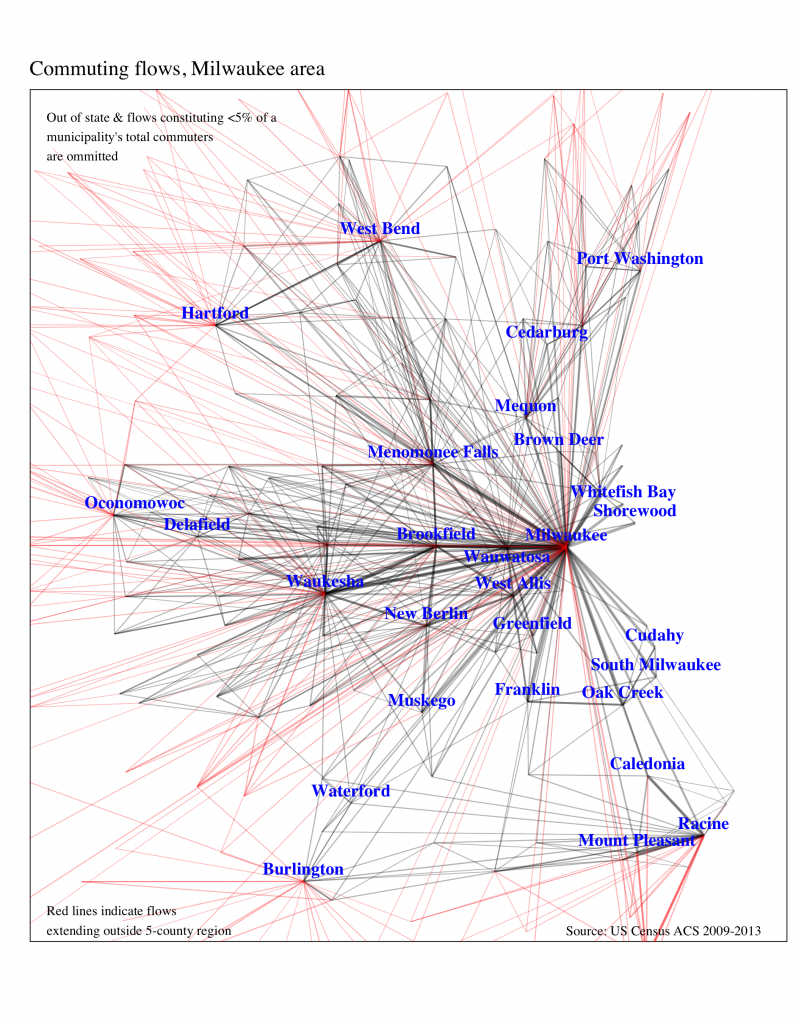

The map above traces commuting flows between each of the 100-plus cities, towns, and villages in the 5-county Milwaukee area. The red lines depict commuters entering or leaving communities outside the region.

In the past, a traditional view of a metropolitan area would likely have been an urban core with many long, straight lines connecting it to the surrounding predominately residential suburbs. This is not the case any longer. In economic terms, the dominant part of the region is now the horizontal axis running roughly west from Milwaukee, through Wauwatosa and Brookfield, and on to Waukesha.

Racine county is less connected. It sends quite a few workers to Milwaukee and Waukesha county, but comparatively few workers travel the other way. Racine is also substantially connected to its neighboring counties of Walworth and Kenosha.

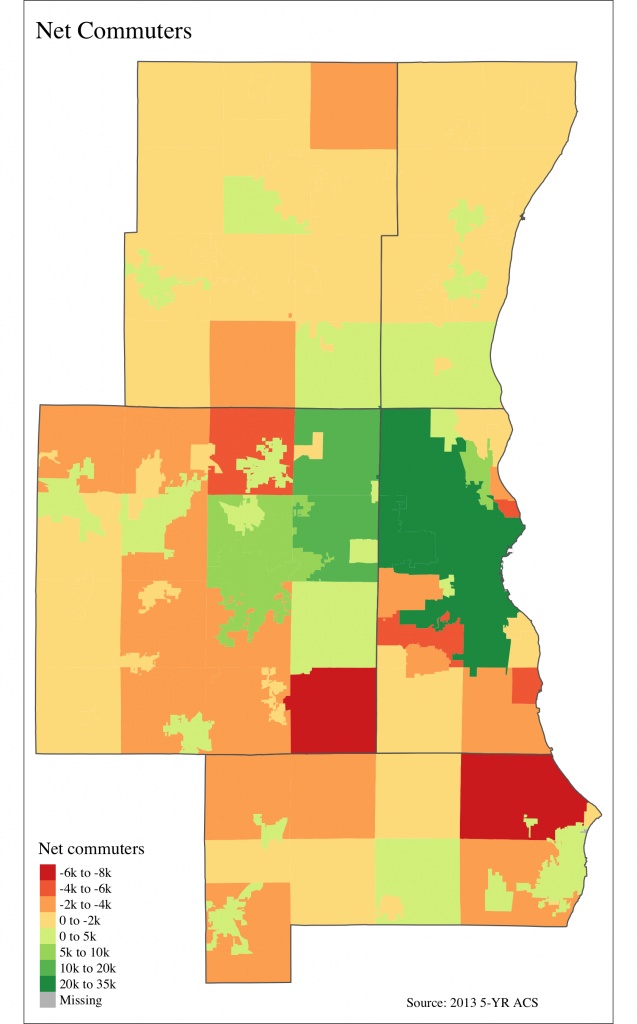

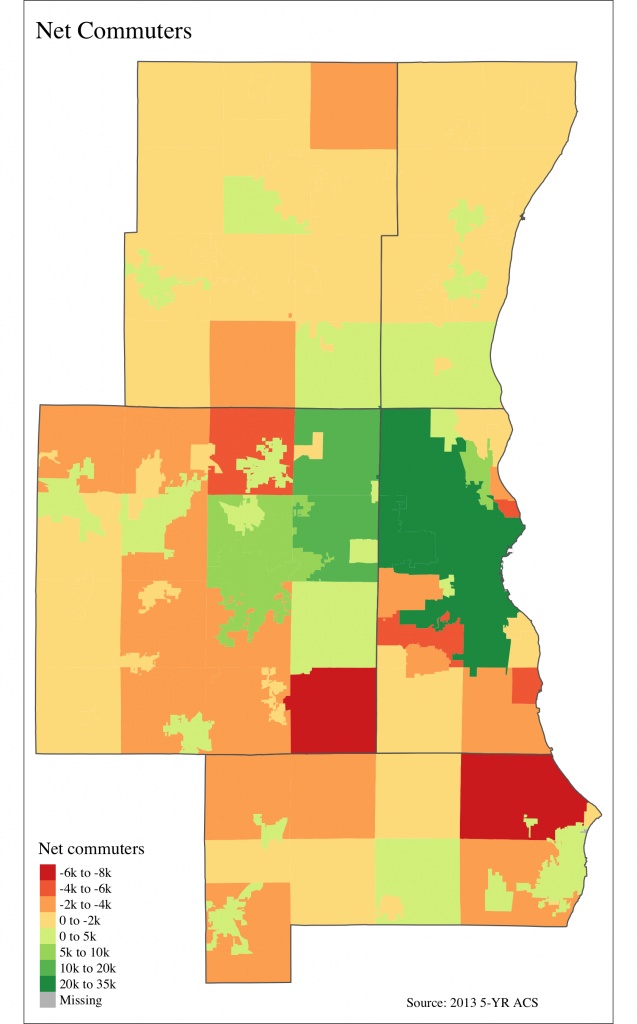

While the above map includes commuting flows in both directions, the one below shows net commuters. Green municipalities have larger populations during the day than at night. Milwaukee city attracts the most workers—some 125,000 in total. Still, nearly 95,000 people leave the city for work every day. Thirty-thousand of them go to Waukesha county, while 30,000 in Waukesha commute to the city of Milwaukee. The net-worker balance between Milwaukee city and Waukesha county is virtually equal.

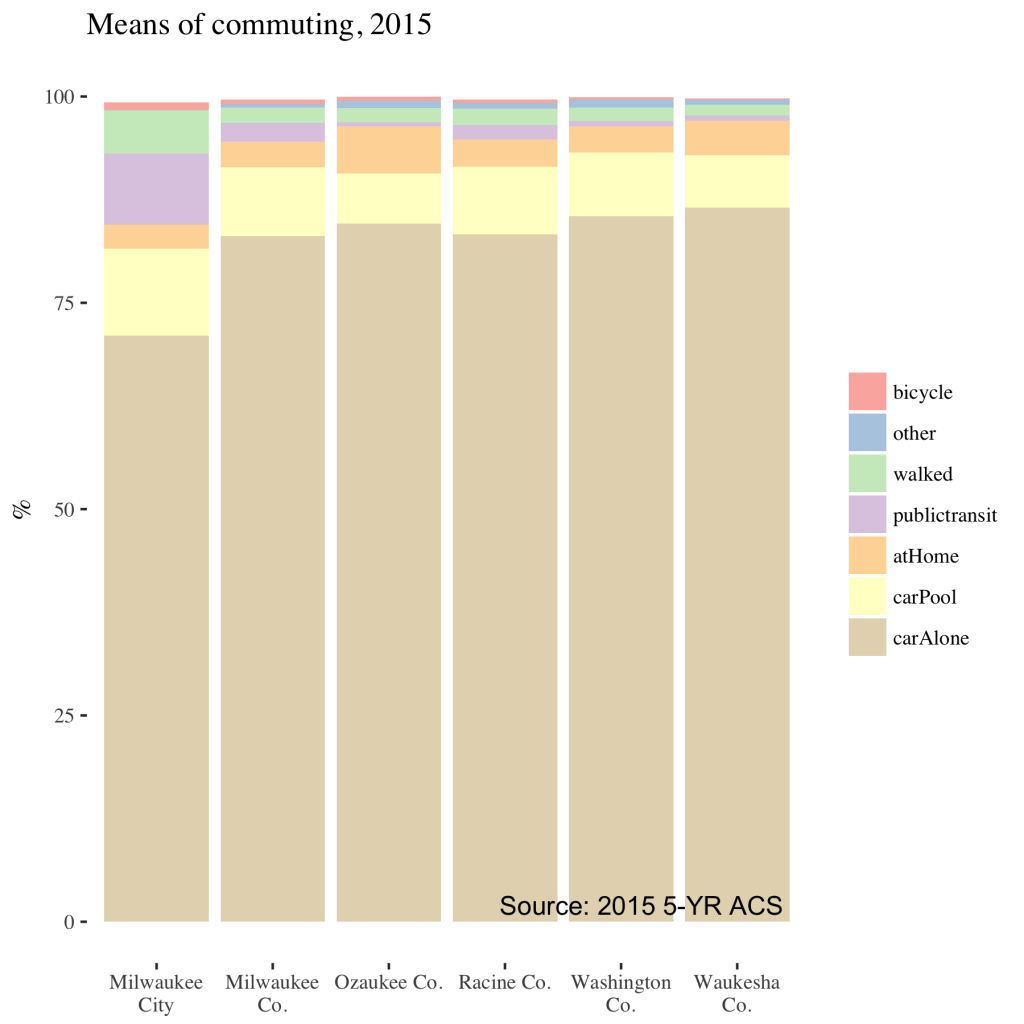

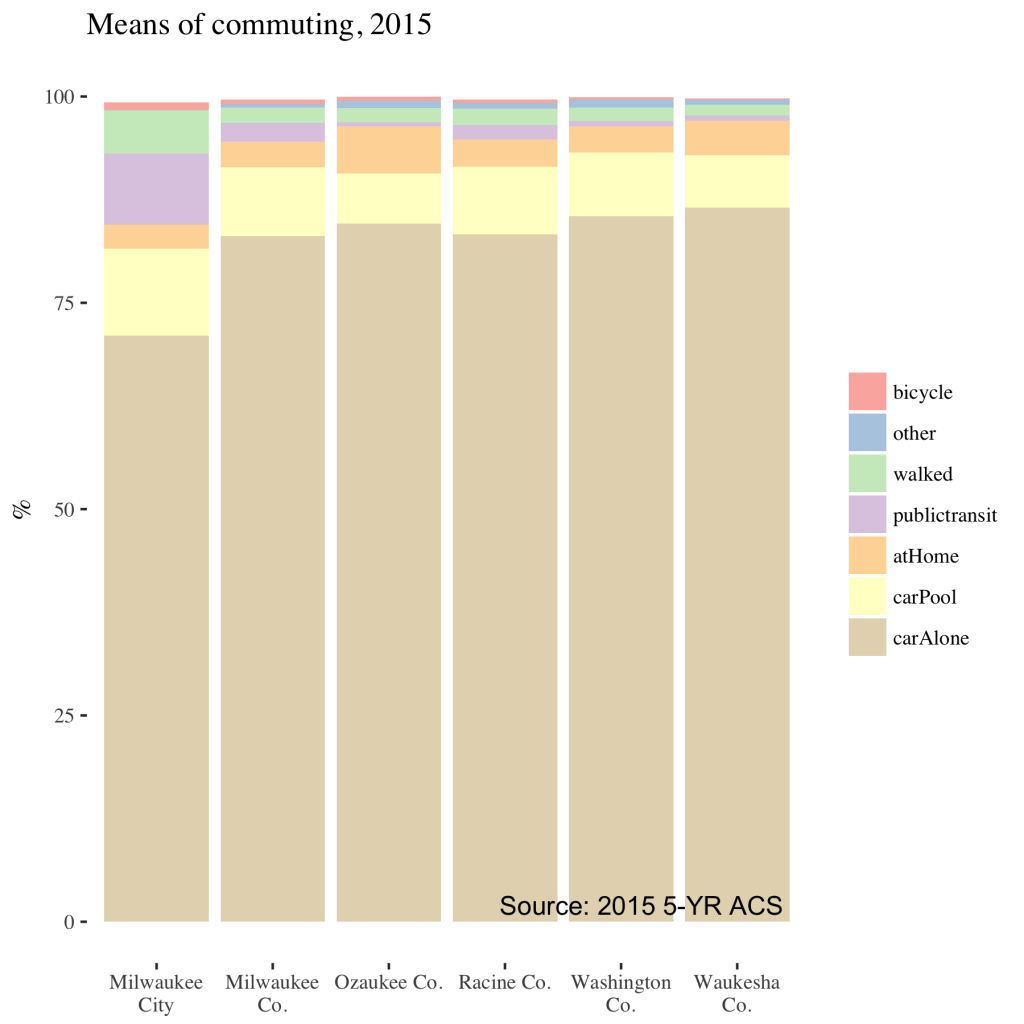

Most people in the Milwaukee area get to work the same way—by driving 20-25 minutes in a car, alone. Regionally 8% carpool, 4% use public transportation, and 3% walk. Differences between the counties are small, as the graph below shows. Milwaukee city workers are the least likely to drive alone. Eleven percent carpool, 9% take public transit, and 5% walk. Working at home is rare everywhere, but it is most common in wealthy Ozaukee county where 6% of workers do so. Half that many do so in the City of Milwaukee.

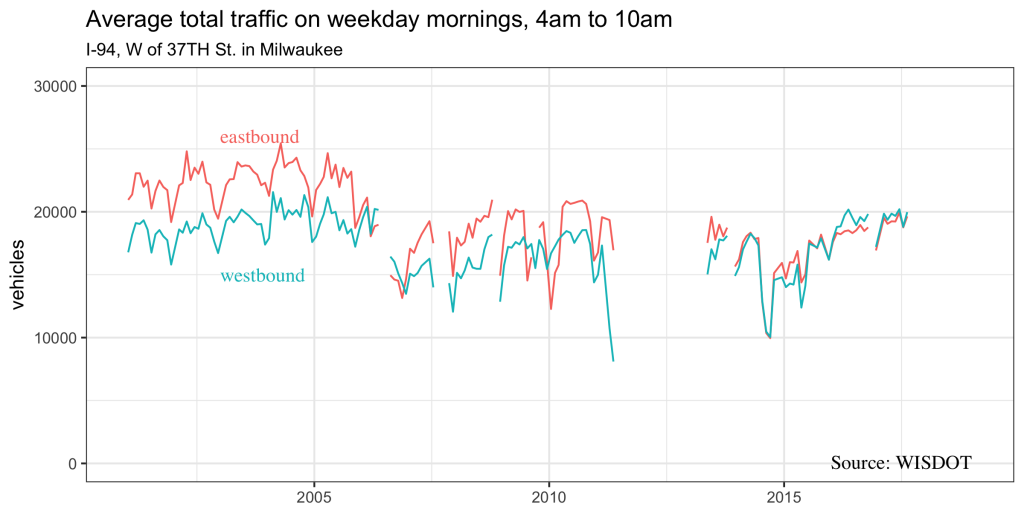

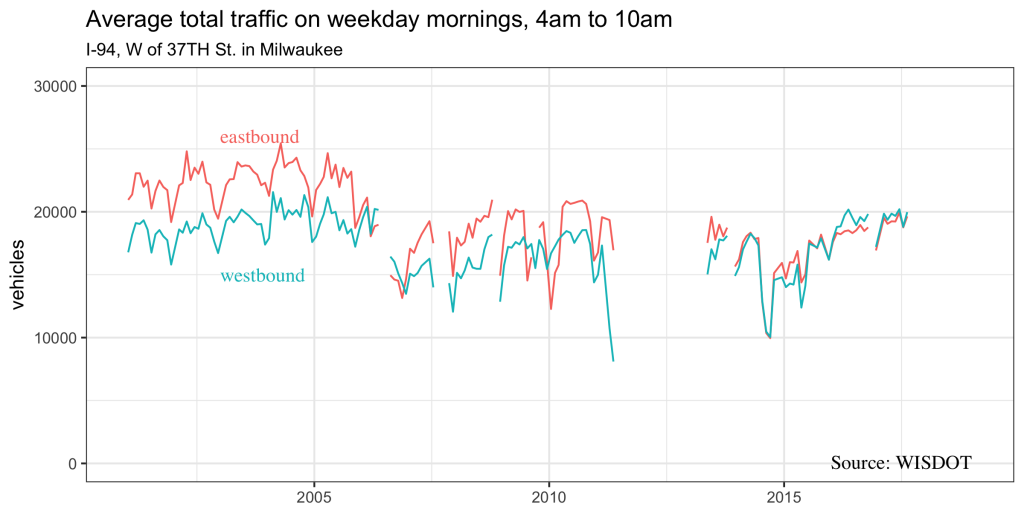

Knowing that the great majority of commuters travel alone by car gives added significance to traffic data. Below we have plotted counts from a Wisconsin Department of Transportation traffic monitor on I-94 just west of 37th Street in Milwaukee. The graph contains all traffic from 4:00 to 10:00 on weekday mornings. Of course, this is not the same as commuting. It includes people driving for other reasons, many people work during other times of the day, and I-94 is just one of the ways people travel to work. Still, the traffic monitor’s location is part of the major east-west commuting axis visible on the commuting flow map discussed above, so we expect traffic trends to reflect commuting patterns to a considerable degree.

Sure enough, while eastbound flows outnumbered westbound flows during the early 2000s, the recovery from the Great Recession has seen the two converge at around 20,000 in each direction every weekday morning. This is consistent with the 30,000 commuters between Waukesha county and Milwaukee estimated by the Census Bureau.

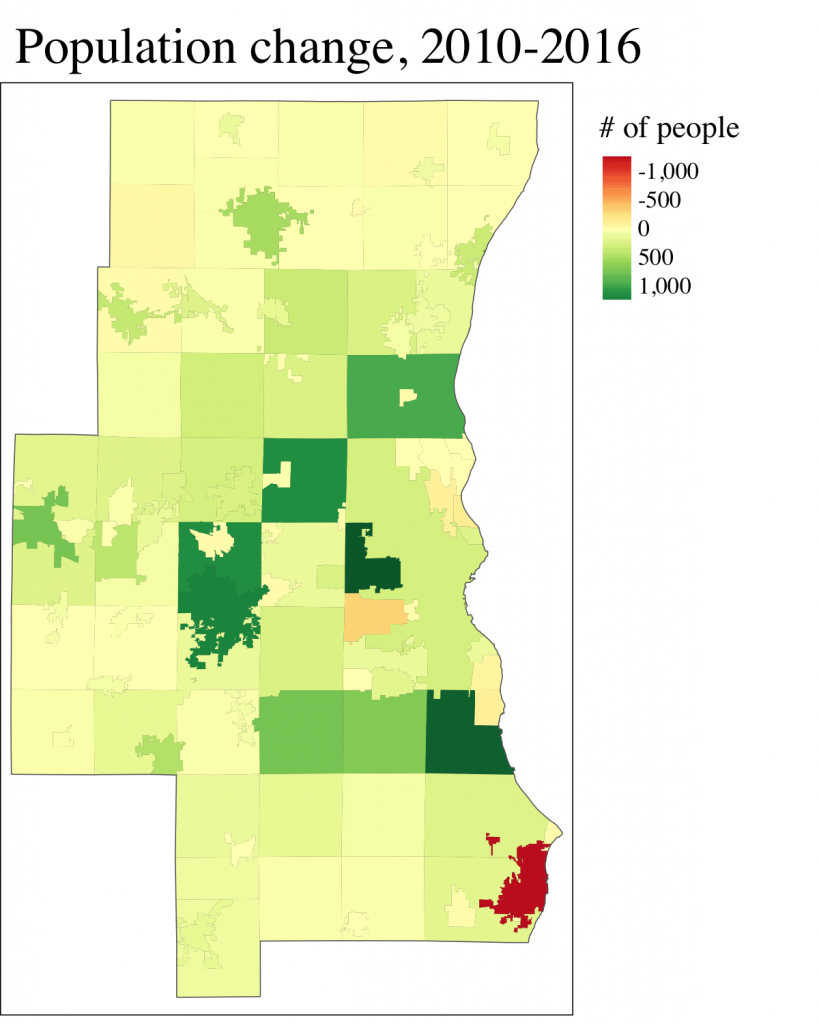

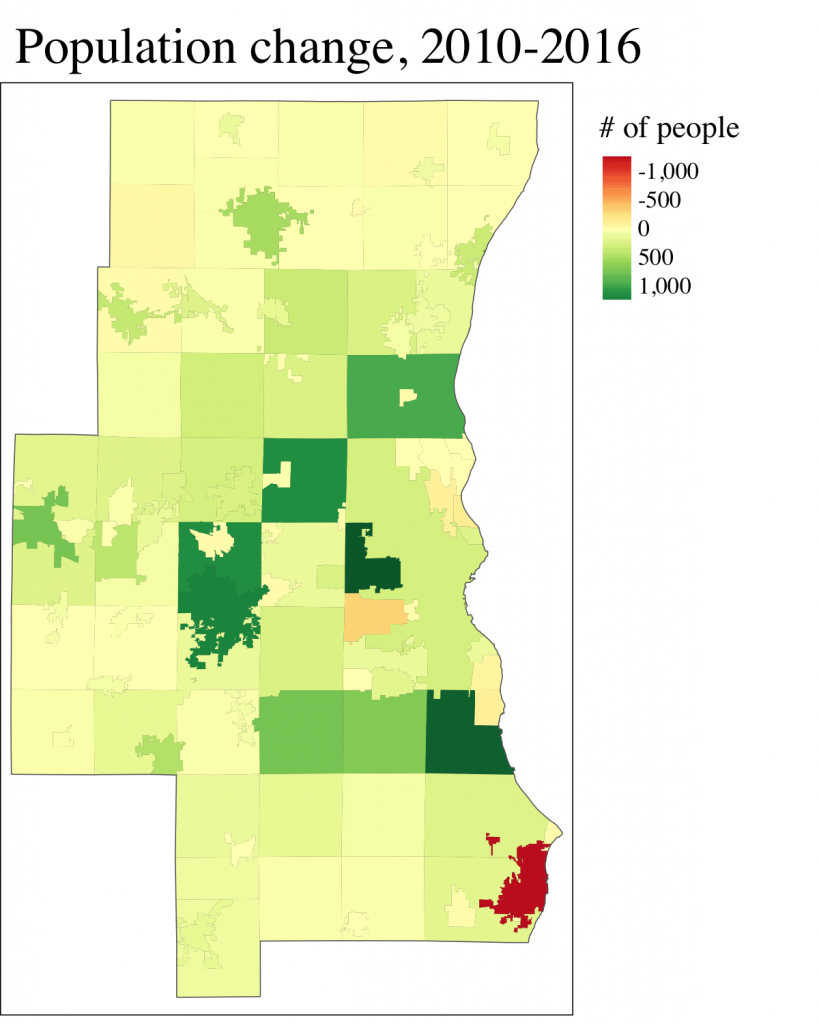

Though it has declined in recent years, moving for work is a common cause of migration.[1] Given this, it’s not a surprise that the map of municipal population growth below share similarities with the map of net commuters. Places where people travel to work are also frequently (but not always) places where people want to live. Racine city is a notable exception. Leaving aside the City of Milwaukee, growth has slowed from the 1990s. The Milwaukee area’s growth is also low in comparison to more dynamic areas of the state like Dane county.

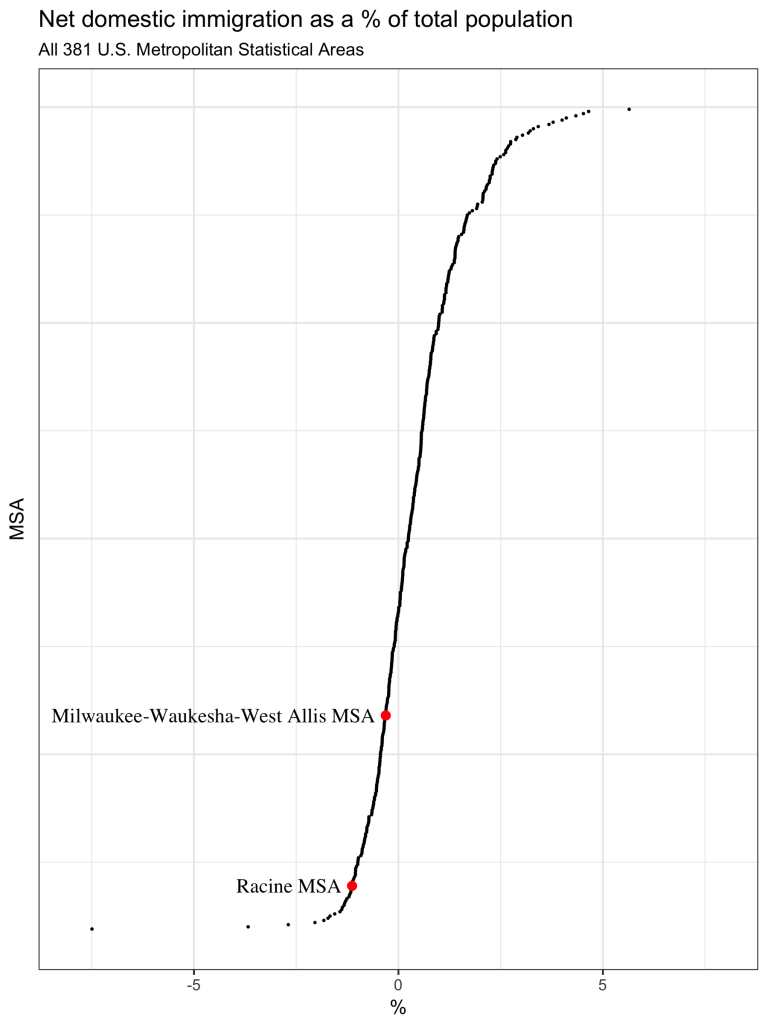

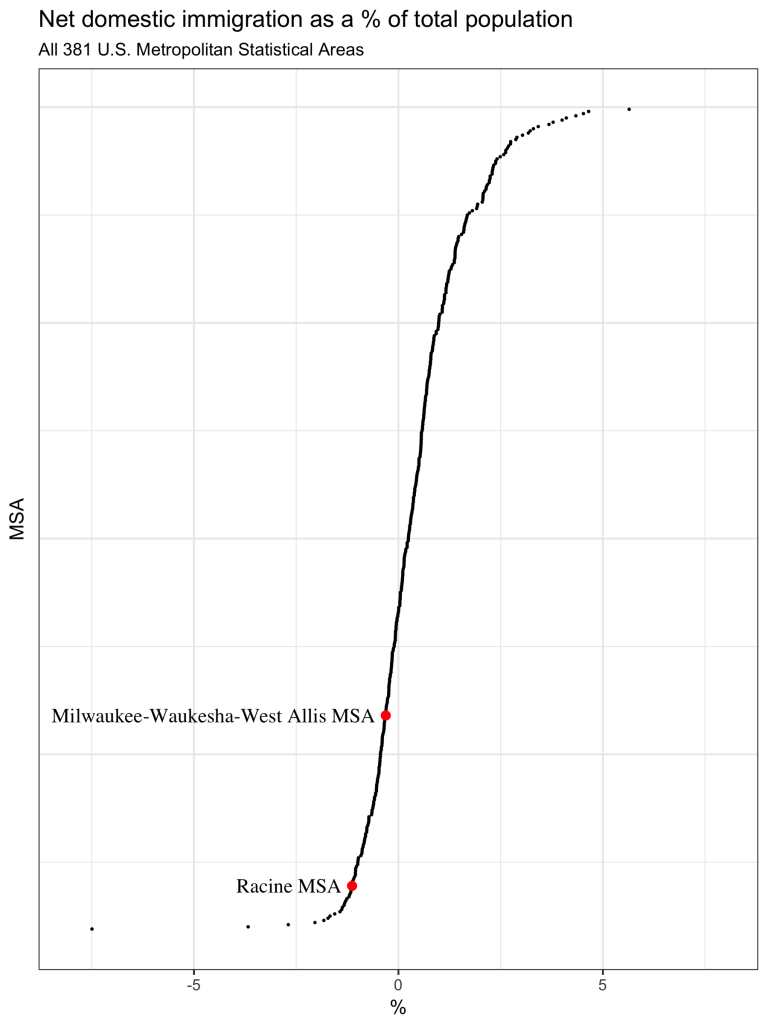

One reason for slow growth is the region’s subpar record in drawing new residents from outside the area. The chart below shows net domestic migration as a percent of total population for each metropolitan statistical area in the United States. Both MSAs in the 5-county area lost more people to domestic migration than they gained. To be clear, this doesn’t include people who entered or left the country.

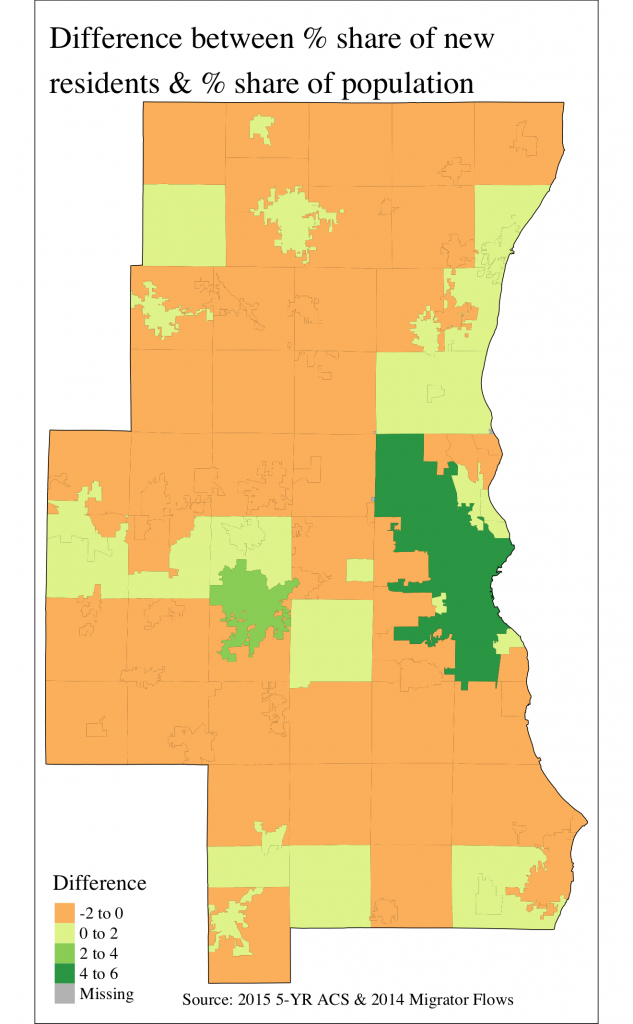

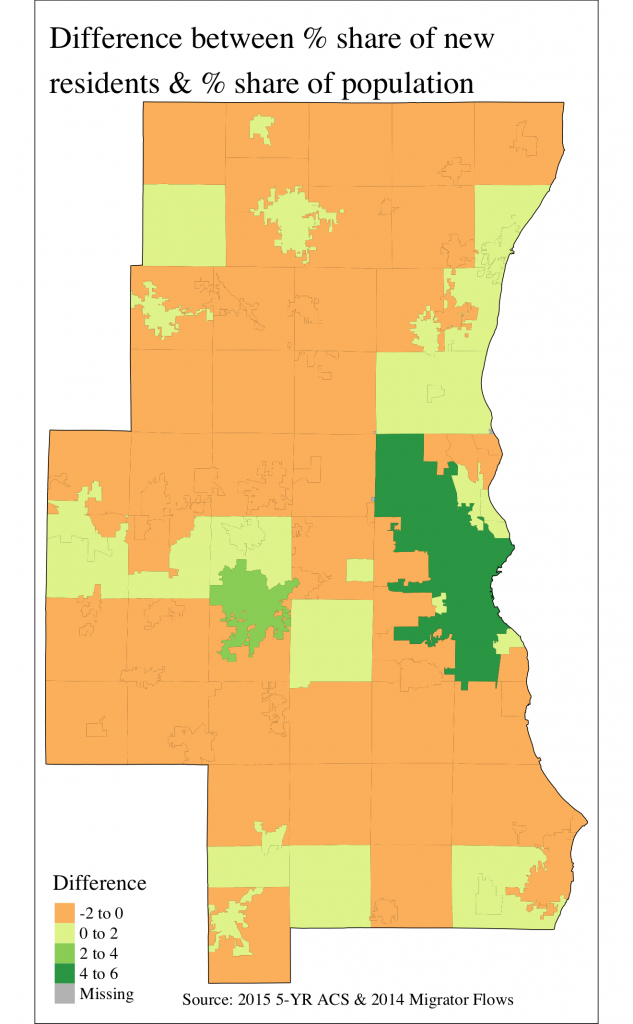

When people do move to the 5-county area from elsewhere, they are most likely to move to one of our two major cities—Milwaukee or Waukesha. Thirty-four percent of the region’s population lives in the city of Milwaukee, but the city attracts 39% of new movers. Waukesha’s share of newcomers is also disproportionately large.

This attractiveness to migrants is likely connected to Milwaukee’s recent growth in total establishments. Population growth and business growth operate in a positive feedback loop, so the attractiveness of Milwaukee to certain kinds of migrants is both a cause and an effect of the economic boom taking place in some parts of the city.

[1] http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/02/13/americans-are-moving-at-historically-low-rates-in-part-because-millennials-are-staying-put/

Rita Aleman has been named the program manager of Marquette Law School’s new Lubar Center for Public Policy Research and Civic Education.

Rita Aleman has been named the program manager of Marquette Law School’s new Lubar Center for Public Policy Research and Civic Education.