Peace Be With You … And With You?

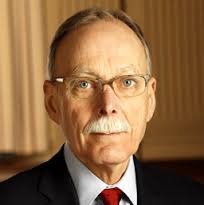

Under the heading of hard bargaining tactics gone bad (and bad lawyer advice), we can now add this story. When a group of eight faculty members at the General Theological Seminary in Manhattan decided to stop working in order to protest their newly hired dean and president, Rev. Kurt H. Dunkle, all purgatory broke loose. Under advice of their counsel, the faculty wrote a rather strongly worded letter outlining their demands regarding the dean. (See the nasty details of the dean’s behavior here.)

Under the heading of hard bargaining tactics gone bad (and bad lawyer advice), we can now add this story. When a group of eight faculty members at the General Theological Seminary in Manhattan decided to stop working in order to protest their newly hired dean and president, Rev. Kurt H. Dunkle, all purgatory broke loose. Under advice of their counsel, the faculty wrote a rather strongly worded letter outlining their demands regarding the dean. (See the nasty details of the dean’s behavior here.)

Unimpressed with the tone of the letter, the Board of Trustees for the Seminary considered the letter, instead of the opening bid that the faculty intended, as a mass resignation. They dismissed the eight faculty members (leaving the students at the Seminary with only two instructors.) In this case, the eight faculty members’ hard bargaining tactic to have their foul-mouthed, micromanaging (in their descriptions) dean dismissed ended up focusing attention on their perceived “bad” behavior rather than that of their dean.