Forty-five years ago, the baseball world trained its attention on the Wisconsin Supreme Court and its impending decision in the case of Wisconsin v. The Milwaukee Braves, soon to be reported as 144 N.W.2d 1 (1966). At issue was whether or not a Milwaukee trial judge, acting on behalf of the state of Wisconsin, could prevent the Milwaukee Braves Major League Baseball team from relocating to Atlanta.

Forty-five years ago, the baseball world trained its attention on the Wisconsin Supreme Court and its impending decision in the case of Wisconsin v. The Milwaukee Braves, soon to be reported as 144 N.W.2d 1 (1966). At issue was whether or not a Milwaukee trial judge, acting on behalf of the state of Wisconsin, could prevent the Milwaukee Braves Major League Baseball team from relocating to Atlanta.

After the Braves’ Chicago-based owners announced their plans to move to Atlanta, Georgia for the 1966 season, a criminal complaint was filed in Milwaukee County Circuit Court alleging that the Braves and the other nine teams in the National League had conspired to deprive the city of Milwaukee of Major League Baseball, and, moreover, had agreed that no replacement team would be permitted for the city. As such, the complaint alleged, the defendants were in violation of the Wisconsin Antitrust Act.

The defendants initially removed the lawsuit to the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Wisconsin, but on December 9, 1965, District Court Judge Robert Tehan remanded the case to the state circuit court where trial was conducted by Circuit Court Judge and former Marquette Law School professor, Elmer W. Roller.

On April 14, 1966, only hours before the Braves opened the season with a game against the Pittsburgh Pirates in Atlanta, Judge Roller ruled that the owners of the Braves and the other National League teams had acted in “restraint of trade” and thus were in violation of the Wisconsin Antitrust Act.

As a consequence, Roller fined the defendants $55,000, plus costs, and enjoined the Braves from playing their 1966 home games anywhere other than Milwaukee, unless the National League agreed to place a new team in Milwaukee in 1967. To give the National League time to make arrangements for an expansion team for 1967, Roller stayed his judgment until mid-June, an act that allowed the Braves to continue playing in Atlanta.

The Braves owners immediately appealed Roller’s decision to the Wisconsin Supreme Court, and the court agreed to hear the case on an expedited basis. On June 9, 1966, the appeal was argued on a day on which the Braves, who never had a losing season while in Milwaukee, sat in 6th place in the National League with a record of 25-30.

With the stay extended, the Braves continued to play in Atlanta, and six weeks later, on July 27, a day that would end with the Braves having slumped all the way down to 8th place, the Wisconsin Supreme Court overturned Roller’s lower court ruling by a narrow vote of 4-3. (Interesting to note is the fact that Supreme Court Justice E. Harold Hallows, who was also a law professor at Marquette, was one of the three dissenters who would have allowed Roller to enjoin the move to Atlanta.)

The Court’s majority’s opinion was based on two different rationales, and while not all of the four justices that made up the majority embraced both theories, each embraced at least one of the two. The first conclusion was that Organized Baseball’s exemption from the federal antitrust laws most recently upheld in Toolson v. New York Yankees (1953), extended to state antitrust rules as well. In the alternative, the majority opinion found that even if Organized Baseball was not exempt from state antitrust regulation generally, the portion of the remedy imposed by Judge Roller that ordered the National League either to return the Braves to Milwaukee or else give the city a new team ran afoul of the United States Constitution’s Commerce Clause and constituted an unenforceable interference with interstate commerce. The majority did, however, confirm Roller’s finding of facts concerning the monopolization of baseball in Milwaukee.

The three dissenters disagreed with both of the majority theories and concluded instead that Congress should be presumed to have left the regulation of Organized Baseball to the states until such time that it explicitly exercised its own regulatory authority. They also maintained that the legitimate interests of the state of Wisconsin in this case took priority over the “restrictive effect on interstate commerce that might result from the enforcement of Wisconsin’s laws.”

Not willing to concede defeat after such a narrow loss, the state of Wisconsin appealed the majority’s decision to the United States Supreme Court. However, pending a decision on the state’s petition for a writ of certiorari, Judge Roller’s lower court order was dissolved, and the Braves were free to play out the season in their new southern home.

Although the Braves lost again on July 28, to fall into 9th place, 14 ½ games behind the first place Pittsburgh Pirates, the Wisconsin Supreme Court decision seemed to clear away the cloud of bad play that had hung over the team all season. After falling to 45-55 on the 28th, the “Atlanta” Braves played inspired baseball the rest of the season, and ended up with a record of 85-77, good for 5th place (out of ten teams), and within 10 games of the pennant-winning Los Angeles Dodgers who overtook the Pirates.

(The year before the Milwaukee Braves had similarly finished in 5th place with a record of 86-76, eleven games behind the Dodgers. However, the previous season had played out in a quite different manner, as the Braves were in first place as late as August 18, before finishing in a 17-27 downward spiral.)

Milwaukeeans had to wait until December 12 to learn that the United States Supreme Court had denied the state’s petition for certiorari. However, in an uncharacteristic move, the Court revealed that it was badly divided on whether or not to hear the case. Justices William O. Douglas, Hugo Black, and William Brennan, it turns out, were in favor of hearing the case, but the cert. petition was opposed by Chief Justice Earl Warren and Associate Justices Potter Stewart, John Marshall Harlan II, Byron White, and Tom Clark.

Although he had taken the oath of office as a Supreme Court justice on October 4, recently appointed Justice Abe Fortas, according to the Court’s announcement, “took no part in the review of the petition.” Consequently, the attempt to involve the nation’s highest court died as a result of the failure of a fourth justice to support the petition.

In another unusual development, Wisconsin filed a petition requesting that the Court rehear the petition for certiorari, perhaps in hopes that Fortas might be now willing to support the petition, but this request was also denied. On January 23, 1967, the litigation over the Braves departure finally came to an end when the Court simply announced that the rehearing petition had been denied and that Justice Fortas had not participated in the review.

Thus, by late January it was clear that the city of Milwaukee would be without major league baseball for 1967. When the National League announced in November 1967, that it would be adding two additional teams for the 1969 season, Milwaukee applied for one of the franchises, as did groups from Dallas-Ft. Worth, Denver, Buffalo, San Diego, Toronto, and Montreal.

However, when the two new franchises were awarded in May of 1968, the National League ignored Milwaukee and awarded teams to San Diego and Montreal. (In the minds of many Milwaukeeans, the 1968 rejection was a form of retribution for the city’s filing suit against the league back in 1965.) As a result, except for 20 Chicago White Sox games played in County Stadium in 1968 and 1969, Milwaukee remained without Major League Baseball until 1970, when Bud Selig and his associates bought the bankrupt Seattle Pilots shortly before Opening Day and moved the one year old team to Milwaukee, where they were renamed the Brewers.

The most interesting question arising out of the Milwaukee Braves litigation is why the Braves were so anxious to leave Milwaukee in the mid-1960’s. After relocating to Milwaukee in 1953 (from Boston, where the team had played since 1871), the Braves were for the rest of the decade one of the showpiece franchises of all of baseball. In a decade in which attendance at major league baseball games steadily eroded, the Braves set one National League attendance record after another.

Part of the answer to the question lies in the fact that in the mid-1960’s Atlanta simply held much greater potential than Milwaukee as a source of revenue for a Major League baseball team. Not only was it based in a larger and still rapidly growing metropolitan area, but it was also located in an area (the Southeast) without Major League Baseball. In contrast, Milwaukee was bounded by the Chicago Cubs and White Sox to the South, the Minnesota Twins to the West, Lake Michigan to the East, and the under-populated wasteland of Northern Wisconsin to the north.

In other words, Atlanta’s superior location provided greater opportunities both for live attendance and for the sale of increasingly important broadcasting rights.

However, after the wave of team relocations between 1953 and 1961, Major League owners had become clearly reluctant to permit additional teams to change cities in search of greater revenues, particularly if it would leave the vacated city without a team. The proposals of Kansas City Athletics owner Charlie Finley to move his struggling team to various cities, including Dallas-Ft. Worth, Atlanta, Louisville, and Oakland had been regularly rebuffed in the years between 1962 and 1966. It was highly unlikely that the other owners would have approved the Braves relocation to Atlanta in 1966, had the only reason to move been a desire to make greater profits.

The sad reality was that between the mid-1950’s and the mid-1960’s, Milwaukee appeared to have gone from being a hotbed of baseball attendance to a city in which the citizenry seemed no longer willing to go to the ballpark to support their team, even if the team was still a pennant contender. Although this was something of a misperception, it is easy to understand why many observers in the 1960’s adopted that view.

The following are the attendance totals for Milwaukee between 1953 and 1965, with the team’s rank among major league teams in parentheses. The totals for 1953, 1954, and 1957 represented new National League attendance records.

YEAR ATTEND. RANK

1953 1,826,397 (1st of 16)

1954 2,131,388 (1)

1955 2,005,836 (1)

1956 2,046,331 (1)

1957 2,215,404 (1)

1958 1,971,101 (1)

1959 1,749,112 (2)

1960 1,497,799 (6)

1961 1,101,441 (9 of 18)

1962 766,921 (14 of 20)

1963 773,018 (16)

1964 910,911 (10)

1965 555,584 (19)

The reasons for the fall off in attendance after 1957 are complicated, especially given the fact that the team had a winning record during each of the thirteen seasons that it played in Milwaukee.

Fan exhaustion may have been a factor. This was certainly a much mentioned explanation in the press in the early 1960’s. The Braves were located in one of the smallest markets in major league baseball, and Milwaukee’s attendance totals represented a much higher percentage of the metropolitan population than that of any other major league team in the 1950’s.

For example, in 1960, which was not one of the Braves better years attendance-wise, the team’s attendance amounted to 130% of the population of the Milwaukee metropolitan area. In contrast, the attendance of the two league champions in 1960, the Pittsburgh Pirates and New York Yankees, amounted to 81% and 11% (!), respectively. For the major league attendance leader, the Los Angeles Dodgers, the ratio was 33%. For several years in the mid-1950’s, the Braves’ annual attendance was essentially double the population of the Milwaukee metropolitan area, a phenomenon achieved nowhere else in baseball history.

Of course, not all of those who attended Braves game came from the Milwaukee area. The team, in fact, regularly drew fans from throughout the state of Wisconsin, and the establishment of the Twin Cities-based Minnesota Twins may have cost the team fans from the western and central part of the state. (The Twins drew 1.5 million fans in 1961, and a significant portion of them came from Wisconsin.)

However, the drop in attendance was also related to the team’s perceived declining performance beginning in 1960. By one measure, the Milwaukee Braves were the most consistently successful team in major league baseball history, finishing, as already mentioned, with winning records in each of their 13 seasons in Milwaukee. On the other hand, the Braves were significantly more successful relative to their competition in their first eight seasons than in their last five.

After finishing second in the National League in 1953 and third in 1954, the Braves went on a remarkable run. In 1955 and 1956, they finished second behind the Brooklyn Dodgers, and by only one game in the latter year. They then won National League championships in 1957 and 1958 (and the World Series in 1957), and then finished in a tie for first place in 1959 with the now Los Angeles Dodgers. (Unfortunately, they lost the 1959 play-off series, and thus missed a third straight World Series.)

In 1960, the Braves were in first place as late as July 24, but a 36-30 record over the remainder of the season left them in second place, seven games behind the surprising Pittsburgh Pirates. Although the Braves actually won more games in 1960 than they did in 1959, baseball fans, then as now, were much more attuned to a team’s place in the standings than to its actual win-loss record. Accordingly, attendance at Braves games began to decline noticeably in August and September 1950, especially once it became clear that the Braves were not likely to catch the first place Pirates.

Although most Braves fans expected Milwaukee to return to the top of the National League in 1961, the team finished a disappointing fourth, its lowest finish since arriving from Boston in 1953. Once again, the decline was not as steep as the standings suggested. Even though the Braves lost all-star catcher Del Crandall with a shoulder injury shortly after the season began and number three starter Bob Buhl suffered a noticeable loss of efficiency as he struggled to a 9-10 season record, the team’s win total for the season declined only by five games. Offensively, the 1961 Braves scored 712 runs, compared to 724 in 1960, and the number of runs allowed by Brave pitchers actually improved ever so slightly from 658 to 656.

The situation appeared even worse in subsequent years as the Braves finished fifth, sixth, fifth, and fifth again in their final four years in Milwaukee (even while each year winning between 84 and 88 games in a 162-game season). Attendance plummeted steadily throughout the period even though the team was usually in the pennant chase for the better part of the season.

Accustomed to having a team at the top of the standings, Milwaukeeans seemed much less interested in a team in the middle of the pack, even if the team had a winning record and continued to feature star players like Hank Aaron, Eddie Mathews, Warren Spahn (through 1964), and Joe Torre.

There is little reason to blame the Braves for allowing the team to decline by ignoring the team’s roster. Although some of the Braves stars of the 1950’s, like Red Schoendienst, Wes Covington, Johnny Logan, and Billy Bruton, disappeared from the team’s roster in the early 1960’s, the Braves roster remained a talented one. The 1962 National League All-Star team, for example, featured six Milwaukee Braves among its 25 man roster.

When necessary, the Braves were willing to take on the contracts of established players to fortify the line-up. For the 1961 season, for example, they acquired all-star infielders Frank Bolling and Roy McMillan and power hitting outfielder Frank Thomas, each of whom was a regular on that year’s team, and, with Bolling and McMillan, for several years after that. Although the team’s focus shifted to the use of players from its successful farm system after 1961, when necessary, the team was willing to acquire established Major League players like Ed Bailey, Gene Oliver, Johnny Blanchard, Billy O’Dell, Ken Johnson, and Felipe Alou.

The Braves also continued to be one of the better franchises in developing young players and by mid-decade, the team’s roster included new stars like pitchers Tony Cloninger and Denny Lemaster, shortstop Denis Menke, and outfielder Rico Carty, who just missed being the 1964 Rookie of the Year after batting .330. (Perhaps the least significant personnel move of the era was the decision to promote minor league catcher and Milwaukee native Bob Uecker to the major league team in 1962.)

The real problem for the Braves in the early 1960’s was that they had to compete against teams like the Los Angeles Dodgers, San Francisco Giants, Cincinnati Reds, and St. Louis Cardinals of that era. Baseball talent was concentrated in the National League in the early 1960’s, and an impressive number of future Hall-of-Famers were entering the prime of their careers during the Braves’ final years in Milwaukee.

The Dodgers in those years were led by pitchers Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale, who shattered existing strikeout records, and by shortstop Maury Wills who broke Ty Cobb’s supposedly unbreakable stolen base record. The Giants, in contrast, relied on power rather than speed, with a line-up that featured Willie Mays, Orlando Cepeda, Willie McCovey, who combined for 541 home runs between 1961 and 1965 (including 226 by Mays alone), and by the three Alou Brothers, and by pitcher Juan Marichal.

The Reds of this era featured Frank Robinson, Vada Pinson, and Pete Rose, and a pitching staff that produced six 20-game winners between 1961 and 1965. The Cardinals who finished the five year period from 1961 to 1965 with a combined record seven games better than Braves included players like the aging Stan Musial and younger stars of the caliber of Ken Boyer, Bill White, Dick Groat, Lou Brock, Curt Flood, and the incomparable Bob Gibson.

The Braves experience in the 1960’s of sharply declining attendance in spite of a successful team on the field was not without recent precedent. Between 1948 and 1950, the American League’s Cleveland Indians saw their total attendance decline from 2.6 million to 1.7 million, in spite of having winning seasons each year. Moreover, in spite of never finishing lower than second place between 1951 and 1956, the Indians saw their attendance further decline from 1.7 million to 900,000. The following table illustrated the decline in attendance in the face of consistent winning seasons that occurred in Cleveland in the late 1940’s and early to mid-1950’s.

YEAR FINISH ATTN.

1947 4th 1.5m

1948 1st 2.6

1949 3rd 2.3

1950 4th 1.7

1951 2nd 1.7

1952 2nd 1.4

1953 2nd 1.1

1954 1st 1.3 (best won-lost record in American League history)

1955 2nd 1.2

1956 2nd 0.9

The conventional explanation for the decline in Indian attendance was the Cleveland fan’s frustration at the inability of his team to overcome their hated rivals, the New York Yankees, who won the American League pennant in each of the above years, except for 1948 and 1954 when the Tribe finished ahead of the Bronx Bombers.

Although the Milwaukee Braves 1961 season was hardly a failure in terms of either on the field performance or attendance, it was the first year since arriving from Boston that the team failed to turn a profit. The team’s attendance dropped by almost 400,000 fans, and the decline in attendance revenue, combined with the fact that the Braves probably had the highest payroll in the Major Leagues, converted a $500,000 profit in 1960 into an $80,000 loss in 1961. (The decision to shore up the team with veterans like Roy McMillan, Frank Bolling, Frank Thomas, and Johnny Antonelli , acquired before or during the 1961 season, had greatly inflated the team payroll, but obviously did not lead to a rebound in attendance.)

Some observers attributed the decline in attendance to a new city ordinance that took effect for the 1961 season which prohibited fans from bringing their own beer into the park. Although a number of contemporary newspaper stories report how unpopular this ordinance was with Braves fans, it is hard to believe that this explains the decline in attendance. Throughout the 1950’s, the Braves had been credited with having the “highest per capita concessions sales in the major leagues,” so it seems unlikely that having to pay for beer at the ballpark would alone cause such a steep drop in attendance.

Another explanation for the decline in attendance in 1961 was the appearance in the upper Midwest of the transplanted Washington Senators, now playing as the Minnesota Twins. Throughout the 1950’s, the Braves had been popular in western Wisconsin and Minnesota and excursion baseball buses running across the state had been a regular summer feature. The Twins did draw a million and a half fans in their inaugural season, but, again, it is hard to believe that competition from the Twins explains the substantial drop in attendance, any more than does the new restrictions on bringing beer into County Stadium.

This sudden decline in profitability led owner Lou Perini to make a number of changes after the 1961 season. To cut his payroll, the team sold the contracts of recent acquisitions Frank Thomas and Johnny Antonelli to the expansion New York Mets. (Antonelli was washed up and never pitched again, but Thomas hit 34 homeruns for the Mets the following year.) The team also introduced a new slogan “Something new in ‘62” as a way of highlighting its plans to make greater use of players from the team’s farm system, other than bringing in stars from other teams, which had been the apparent strategy in 1961.

Perini also raised ticket prices (as he had before the 1961 season) and for the first time agreed to permit the broadcast of a limited number of Braves games on television. In 1961, the Braves were the only major league baseball team that did not allow any of its games to be televised into its home market, but in 1962, Perini permitted the broadcast of fifteen road games on local television. He also made plans to install an escalator at County Stadium to make it easier for fans to reach the upper deck.

None of this worked to revive fan interest, and in spite of Perini’s increased spending on publicity, the team sold only 6,000 season tickets for the 1962 season, a total which represented a 50% decline since 1959. When the attendance dropped by another 330,000 that year, Perini in frustration agreed to sell the team to a Chicago-based group of investors for a purchase price of $5.5m. Perini, who never personally moved from Boston to Milwaukee, cited the wide-spread operation of his construction company as a reason for the sale.

There is some evidence that suggests that the new owners purchased the team with plans to move it to Atlanta already formulated. However, Atlanta’s planned new municipal stadium would not be ready until 1964 or 1965, so it was necessary to continue to play in Milwaukee whatever their intentions.

In 1963, the new owners sought to recoup part of the purchase price by expanding the number of Brave games on television, agreeing to broadcast five home games during the upcoming season, as well as another package of away games. In addition, the new owners issued and sold stock in the team, but sales were extremely disappointing.

More importantly, rumors of the new owners plans to move the team to Atlanta began to spread almost immediately, a fact that could hardly have helped attendance. Whatever the impact of such rumors, attendance was basically stable in 1963, and the Chicago-group reportedly lost another $60,000.

The situation improved slightly the following year. The 1964 Braves were one of the great offensive teams of that era, scoring over 800 runs and averaging just under five runs per game, which was better than a half run more than the eventual champion Cardinals. Unfortunately, 1964 was the year that the seemingly ageless Warren Spahn ran out of gas at age 43, and Brave pitchers compiled the second highest ERA in the National League. While they were in contention during the early part of the season, sitting in third place, one and a half games back of first place, on May 29, the team slumped in June and spent most of the season in the second division.

A last gasp effort saw the club win 14 of its final 17 games to pull within five games of the first place Cardinals (although still in 5th place). Attendance went up about 200,000 people in 1964, but the season’s total fell below the one million mark.

Throughout 1963 and 1964, rumors were rampant that the new owners planned to move the team to Atlanta. Even with increased attendance and more games on television the team incurred further losses in 1964, totaling a reported $500,000 (!). In light of continued losses, the decision was finally made to relocate the team to Atlanta in time for the 1965 season, and initially the other National League teams supported the move.

However, the Milwaukee County Board threatened to sue to enjoin the relocation of the team unless it complied with the terms of its lease which ran through the 1965 season. A team offer to buy out the lease was rejected by the Board, and in the face of a potential lawsuit, the other National League owners refused to approve the 1965 relocation plan after all. However, they did declare that it was in the best interests of the National League to permit the Braves to move to Atlanta in 1966, essentially confirming the lame duck status of the Milwaukee Braves of 1965.

Fan reaction to this resolution was one of unrepressed anger. Although the Braves were in first place for most of the 1965 season, after opening day, the 1965 season was played under a fan boycott, and barely a half million people showed up for the Braves home games that year. When the Braves did in fact depart after the 1965 season, the case of Wisconsin v. Milwaukee Braves began.

Was there anything that could have been done to prevent the situation that resulted in the Braves departure? In 1965, as a last ditch effort, Wisconsin Senator William Proxmire introduced a bill in the Senate that would have required major league teams to pool all of their radio and television income in a way similar to the then current practice in the National Football League. The bill never got out of committee in the United States Senate, but such a requirement might have reduced the lure of relocating to new territory and perhaps kept the Braves in Milwaukee.

However, short of a structural change of that nature, it is difficult to see how the situation might have been different. The real aberration in Milwaukee baseball history was the attendance figures of 1953-1959, not those for 1960 to 1965. Given its population, Major League Baseball attendance in Milwaukee in the early 1960’s, at least through 1964, was actually pretty good. Selling the team to owners with no commitment to Milwaukee in 1962, probably made it inevitable that the team would soon be relocated to a larger, more lucrative market.

On the other hand, what the Braves really lacked after 1960 was exceptional pitching. In December 1960, fearing that long-time shortstop Johnny Logan was nearing the end of the line and believing that neither of his back-ups, Felix Mantilla and Andre Rodgers (acquired from the Giants earlier in the off-season) were ready to be full-time major league shortstops, the Braves traded pitchers Juan Pizarro and Joey Jay to the Cincinnati Reds for all-star shortstop and Gold Glove winner Roy McMillan.

Although not a strong hitter, McMillan was widely regarded as the best defensive shortstop in baseball, and, teamed with newly acquired second baseman Frank Bolling (obtained in a trade with Detroit for centerfielder Billy Bruton), he gave the Braves the best defensive infield in the National League.

However, the two pitchers the Braves traded for McMillan both blossomed in 1961. Joey Jay had first appeared for the Braves in a major league game in 1953 as a 17-year old bonus baby, but had been a disappointment for most of his time with the team. Consequently, even though he had pitched well when inserted in the starting rotation at the end of the 1960 season, he was deemed expendable. Unfortunately for the Braves, Jay won 21 games with the pennant-winning Reds in 1961, tying Spahn for the most wins in the National League and finishing 5th in the National League MVP voting.

Pizarro, who was subsequently traded by the Reds to the White Sox, had shown great promise with the Braves in 1958 and 1959, but had a disappointing season in 1960. However, in 1961, given a chance to start for the White Sox, the left-hander went 14-7 with a 3.05 ERA and led the American League in strikeouts per nine innings.

In 1961, the Braves starting pitching was at best mediocre behind staff aces Warren Spahn (21-13) and Lew Burdette (18-11). Bob Buhl, with Spahn and Burdette the anchor of the staff during the World Series years, slumped to 9-10 with a 4.11 ERA and fourth starter Carl Willey finished only 6-12. Highly regarded rookie pitchers Bob Hendley and Don Nottebart combined for a disappointing 11-14 record, and mid-season call up Tony Cloninger, while posting an impressive 7-2 won-lost log, had an unimpressive 5.25 ERA.

One can never say for certain, but had the 1961 Braves featured a starting rotation of Spahn (21-13), Jay (21-10), Burdette (18-11); and Pizarro (14-7), and a shortstop parlay of Logan, Mantilla, and Rodgers, the chances are good that the Braves, not the Jay-less Reds, would have won the National League pennant that year. Even more importantly, Milwaukeeans would have returned to the ballpark at 1957 and 1958 levels; Parini would have not sold the team to the Chicago investors; and the Braves would still be playing in the Cream City.

At least it’s fun to think that that might have happened.

The saga of the Braves in the 1960’s does raise a number of questions that are beyond the scope of this essay. Why, for example, were Major League Baseball teams in the 1950’s and 1960’s so slow to exploit the economic advantages of local television broadcasting in their own immediate markets? This is particularly interesting in light of the importance of such rights in the modern era. (New York Yankee dominance is currently built on the team’s local cable contract.) Although the Braves were extreme in their refusal before 1962 to allow any of their games to be broadcast into Milwaukee, several teams, including the highly successful Los Angeles Dodgers, refused to allow the broadcast of their home games in that same era.

Finally, what would have happened if the Supreme Court had granted certiorari in Wisconsin v. Milwaukee Braves? One can only guess, but it seems likely that two of the three justices who voted to hear the case—Douglas and Brennan–wanted an opportunity to overrule the Supreme Court’s decision in the 1953 case, Toolson v. New York Yankees (1953), in which the exemption of Organized Baseball from the antitrust laws was upheld. Six years later, in their dissents in Flood v. Kuhn (1972), the two said as much. What Justice Black was thinking in 1966 is less clear, particularly given that he, with a last minute contribution from Warren, had written the court’s per curiam opinion in Toolson.

Of course, a decision overturning Toolson would have been of no immediate benefit to Milwaukee, since if the federal antitrust laws were to be applied to Organized Baseball, that would almost surely mean that they would preempt any application of the Wisconsin Antitrust Act.

The more interesting question is whether it possible that there were five justices on the court in 1967 that would have accepted the broad leeway given to state power by the opinion of the dissenting justices on the Wisconsin Supreme Court? One can never answer such questions with absolute confidence, but if such justices existed, why wouldn’t they have voted to hear the case? Moreover, as constitutional historian Michael Belknap demonstrated in his The Supreme Court Under Earl Warren, the Warren Court was generally hostile to state efforts to regulate the instrumentalities of interstate commerce.

On the other hand, the voting patterns of United States Supreme Court justices in cases involving the sports industry have been notoriously difficult to predict.

In any event, the Braves left town, but life, and baseball, managed to go on in Milwaukee without them.

Author’s note: Growing up in Pearisburg, Virginia, I became a fan of the Milwaukee Braves in 1961 for three reasons. (1) My youth league team, from which I was cut in 1961 but rejoined the following year, was called the Braves. Although our uniforms were green, I associated the Pearisburg Braves with the Milwaukee Braves from the very beginning; (2) My Great-Uncle Kester, “Ket,” Hoke was from Nitro, West Virginia, the home town of Braves star pitcher Lew Burdette, and he was a member of a group of men who went squirrel hunting with Burdette in the off-season; and (3) my oldest baseball card, which dated all the way back to 1959, was of Braves first baseman Joe Adcock who I thought looked a little bit like my Dad.

I followed the Braves intently every year in the 1960’s, and having read about the glory days of 1957 and 1958, I fully expecting them to return to the top of the National League standings. I was not particularly disappointed with the move to Atlanta in 1966 for a couple of reasons. First of all, Atlanta seemed much closer to my home town than Milwaukee, and the arrival of the Braves in Milwaukee allowed for the transfer of the Braves top minor league to Richmond, Virginia, where my cousins lived and where the top Brave farmhands would play for the next forty years.

I have only the vaguest recollection of the lawsuit Milwaukee filed against the Braves, but I do remember much better how widely the fan boycott of 1965 was covered by the press, even in the local Virginia newspapers. Consistent with “following” the Braves to Atlanta, I felt no affinity for the Brewers when they arrived in Milwaukee in 1970. Hence, my years as a Brewer fan only began when I joined the Marquette faculty in 1995. However, when I attended the special ceremony at County Stadium in 1997 honoring the 1957 World Champion Braves, I felt like I was paying tribute to a part of my childhood.

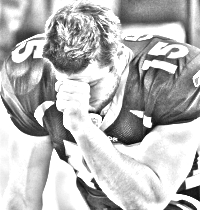

Much has been made of Broncos quarterback Tim Tebow’s outward expressions of his Christian faith, especially his practice of kneeling in moments of prayer—“Tebowing” as it is now called—after touchdowns, some of them admittedly a bit miraculous.

Much has been made of Broncos quarterback Tim Tebow’s outward expressions of his Christian faith, especially his practice of kneeling in moments of prayer—“Tebowing” as it is now called—after touchdowns, some of them admittedly a bit miraculous.