Does One of the Proposed Remedial Redistricting Plans Contain Noncontiguous Districts?

Background

The Wisconsin Supreme Court enjoined the further use of Wisconsin’s existing state legislative maps in any future election when it ruled on December 22, 2023 that the current maps are unconstitutional because they include noncontiguous districts. The state constitution requires “[Assembly] districts to be bounded by county, precinct, town or ward lines, to consist of contiguous territory and be in as compact form as practicable” (Wis. Const., art. IV, sec. IV).

Previously, this provision had been interpreted to allow physically separated sections of a single municipality to be placed in a single district, even if this meant that the district, taken as a whole, lacked contiguity.

The 2023 ruling rejected this flexible definition of contiguity in favor of a strictly literal rule. “[F]or a district to be composed of contiguous territory, its territory must be touching such that one could travel from one point in the district to any other point in the district without crossing district lines.” Clarke v. Wisconsin Elections Commission, 2023 WI 79, ¶ 66. Literal islands don’t violate this requirement. “A district can still be contiguous if it contains territory with portions of land separated by water.” Id., ¶ 27.

Extent of noncontiguity

Seven proposed redistricting plans were submitted to the Supreme Court on January 12, 2024, as discussed in an earlier post. One of them—that of the Democratic Senator Respondents—includes several Assembly districts with noncontiguous land areas.

In an Expert Report submitted to the Wisconsin Supreme Court in support of the remedial maps proposed by the Democratic Senator Respondents, Kenneth Mayer maintains that these districts should not be counted as noncontiguous. “The remaining cases of apparent non-contiguity stem from ward fragments resulting from errors in the underlying Census data, which the parties have agreed should not be counted as noncontiguous” (p. 7 of the report). I discuss below whether this data stipulation has any relevance to territorial contiguity.

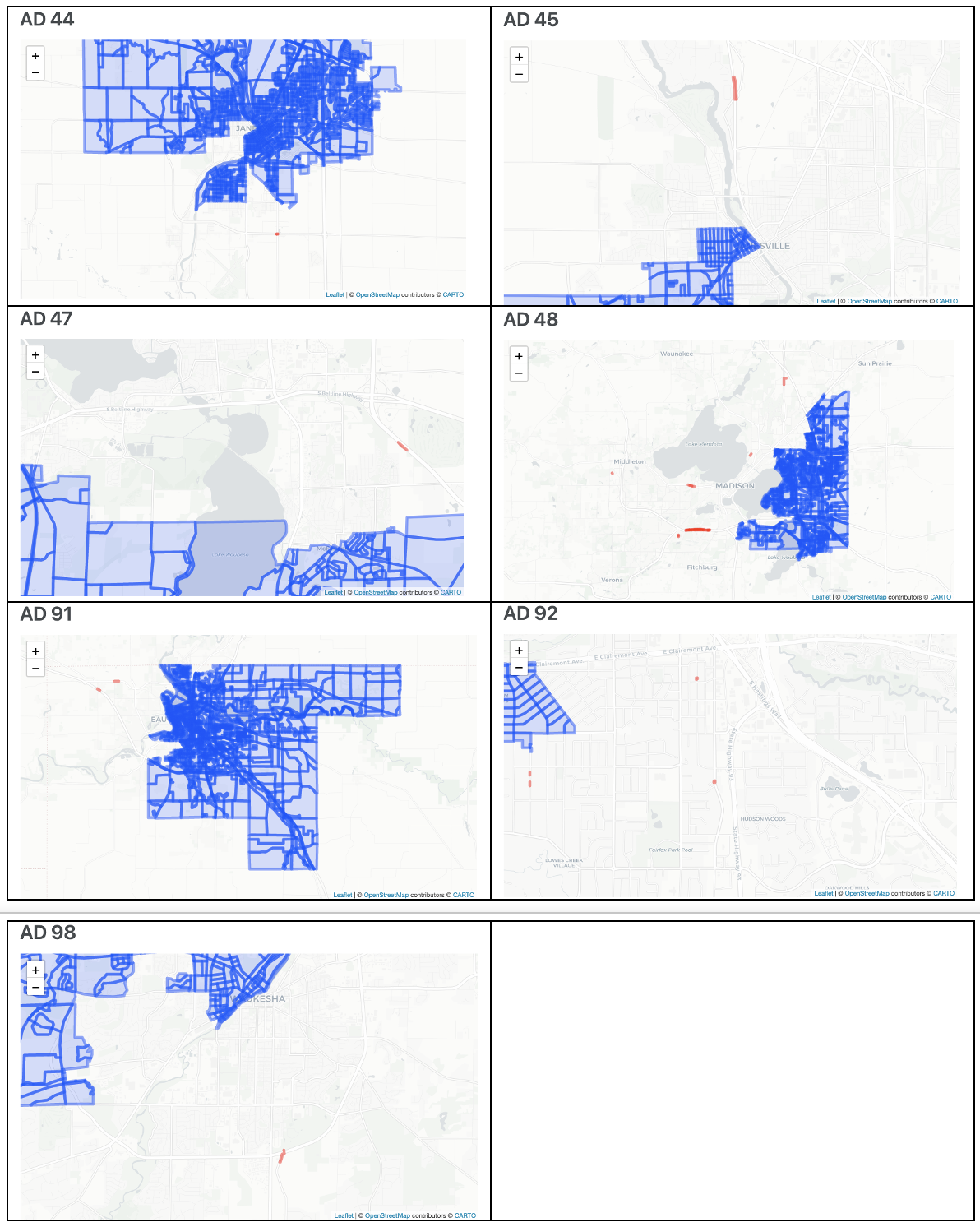

The noncontiguous Assembly districts are the 44th, 45th, 47th, 48th, 91st, 92nd, and 98th. In total, the unconnected segments include 34 census blocks, of which two are populated according to the 2020 census count. The populated blocks are “550250008001000” in AD48 (pop. 88) and “550350008021018” in AD92 (pop. 14). The remaining blocks are generally tiny strips of land and in any event are unpopulated.

The redistricting plans submitted to the Wisconsin Supreme Court are defined by block assignment files—spreadsheets which list each census block in Wisconsin, along with the district to which it is assigned. I obtained the block assignment files for this plan from links shared by Senate Minority Leader Hesselbein on X on January 12th.

I measure district noncontiguity by matching the block assignment files to the Census Bureau’s block GIS file. Then, I measure the adjacency of each census block and identify the components of the resulting network. Replication code is available here.

The following graphics show the noncontiguous sections of each Assembly district. Each block in the main component of the district is outlined in blue. Any disconnected blocks are outlined in red. Click here to view a web page with interactive web maps.

The Joint Stipulation

On January 2, the parties to the case filed a joint stipulation describing a series of deviations, agreed to by all parties, from the official redistricting data.

The stipulation mainly deals with 216 ward fragments, themselves including nearly 300 blocks, with incorrect ward or municipality labels. The incorrect labels seem to originate with the original Census Bureau data. This matters because the parties don’t want to be penalized for splitting a ward (or municipality) when, really, it is the label that is incorrect. In the stipulation, the parties agreed on a consistent way to correct and handle these ward and municipality designations.

The position of the Democratic Senator Respondents is that this stipulation also means that the specified blocks should not be counted as physically noncontiguous with the rest of the district.

Here are the relevant paragraphs from the Joint Stipulation. In his report (p. 7 & n.6), Mayer cites paragraphs 8 and 9. I also include paragraph 7, which may be relevant.

7. All parties agree that the Franklin ward and the 215 additional ward fragments identified in Appendix A do not reflect true municipal-ward “islands,” that is, noncontiguous territory which is separated by the territory of another municipality from the major part of the municipality to which it belongs, see Wis. Stat. § 5.15(1)(b), (2)(f)(3).

8. All parties agree that detaching any of the 216 ward fragments identified in Appendix A from the rest of the ward to which it is assigned in the August 2021 Redistricting Dataset will not count as a ward split when evaluating a proposed remedial map.

9. All parties agree that any of the 216 ward fragments identified in Appendix A will be considered part of the municipality to which the August 2021 Redistricting Dataset and the 2020 Census Redistricting Data assigned it, regardless of whether that assignment may have been due to error in the U.S. Census data, when evaluating a proposed remedial map.

Paragraphs 8 and 9 address whether or not incorrectly labelled blocks should be counted as ward or municipality splits. This has nothing to do with physical contiguity.

The meaning of paragraph 7 is less clear to me. What does it mean to say that the ward fragments are not actually “separated by the territory of another municipality from the major part of the municipality to which it belongs”? What if the ward fragment is separated by another district from the main body of the district to which it belongs?

One thing is clear. The Joint Stipulation does not dispute the actual physical location of any of the census blocks. Using the Census Bureau’s census block GIS file to draw maps defined by the Democratic Senator Respondents’ block assignment files will still result in situations where landbound portions of some districts are unconnected to the rest of the district.