Thinking Like a Lawyer Redux

This week, Marquette University Law School welcomed its Class of 2015. The start of an academic always has an energy to it unlike other times during the year. Excited and nervous 1Ls begin their journey to their J.D.s, steeped those first couple weeks in what seems like a foreign culture with a foreign language. While they’re not exactly sure what they’re going to learn in those 1L classes, new students do understand, within days of being in Eckstein Hall, that what they will learn is how to “think like a lawyer.” Whatever that means. With that, I am reposting something I wrote several years ago that remains important: “Thinking like a lawyer” is a legal skill, not a life skill.

This week, Marquette University Law School welcomed its Class of 2015. The start of an academic always has an energy to it unlike other times during the year. Excited and nervous 1Ls begin their journey to their J.D.s, steeped those first couple weeks in what seems like a foreign culture with a foreign language. While they’re not exactly sure what they’re going to learn in those 1L classes, new students do understand, within days of being in Eckstein Hall, that what they will learn is how to “think like a lawyer.” Whatever that means. With that, I am reposting something I wrote several years ago that remains important: “Thinking like a lawyer” is a legal skill, not a life skill.

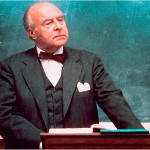

At the start of each academic year, I cannot help but to think of Professor Kingsfield, the notorious contracts professor in The Paper Chase. The various classroom scenes where Professor Kingsfield grills student after student on classic contracts cases like Hawkins v. McGee have for years served as a sort of example of the “typical” 1L experience with the dreaded Socratic method.

While Professor Kingsfield surely sits at one end of the spectrum for professorial style, the Socratic method he uses endures. It is, as one text notes, law school’s “signature pedagogy.” It’s the way the law school professors across the country have been teaching law students about legal analysis for more than a century.

And students learn. They begin their first year of law school with, to paraphrase Professor Kingsfield, “a head full of mush.” Even by the end of that first semester, though, most 1Ls have developed an ability to turn that mush into cogent analysis, to make fine-line distinctions, to look for weaknesses in another’s argument, and to argue both sides of any issue; in other words, they learn to “think like a lawyer.” This “thinking like a lawyer” is undoubtedly a necessary professional skill; however, mastering the process can come at a personal cost.

![IMG_7297[1]](http://law.marquette.edu/facultyblog/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/IMG_729716-300x200.jpg)